By his own admission, Ben Stokes wasn’t the best behaved child in the world.

“I was always an adventurer, a bit of a free thinker,” he wrote in his autobiography Firestarter. A description to strike fear into the heart of any babysitter.

Mark Shaw, who coached a young Stokes in Christchurch, where Stokes lived for the first decade of his life, and Andy Cameron, who was his rep and club coach in Wellington until he was 12, remember this well.

“My son used to knock around with Ben growing up,” says Shaw. “And I guess they got into a bit of trouble as kids, but nothing nasty or anything. They just challenged you. If they were playing at our place, they wouldn’t be at our place. You’d have to go and find them.”

Cameron remembers similarly.

“I always look back at this one particular incident,” Cameron says. “Every year they ran this cricket camp up in the Hawke’s Bay. And kids could get a bit naughty up there.”

Standing at the back of the room, Cameron watched on as the camp leader gave the welcoming spiel to the children, reminding them of the values of the course, that they were here to have fun, learn and listen to their coaches. The speaker’s eyes then scanned to a red-haired boy sitting in the middle of the room.

“Isn’t that right, Mr Stokes?”

Ben Stokes’ first club Merivale Papanui CC in Christchurch (Cameron Ponsonby/The Athletic)

To understand Stokes is to understand the relationship he had with his father, Gerard. An icon of rugby league in Christchurch, he was capped once for New Zealand and was the head coach of the Canterbury Cardinals when Stokes was a child.

“All I ever wanted to do as a young lad was to help him,” Stokes said in Firestarter. “To be around what he was doing.”

Every evening was spent at the rugby club watching Gerard run training, Stokes soaking it all in. When the adults went off to do their drills, he would pick up a kicking tee and a ball, pop himself in front of the posts and take kick after kick with his right foot, and then his left.

Stokes credits this upbringing with moulding his outlook to sport and life. His father was known for being a hard man (not many who make it to international rugby league aren’t), and his aggression and determination in a sporting environment made it down to Stokes.

The oft-told but still legendary story about Gerard is that he chose to have a dislocated finger amputated, rather than re-set, so he wouldn’t miss any matches. As a child, Stokes believed his father’s finger had been lost to a crocodile. Now as an adult, when Stokes scores a century, he holds his hand to the sky with his middle finger folded down, in tribute to his father who died in 2020.

Ben Stokes celebrates his hundred against India this summer – in tribute to his late father Gerard (Gareth Copley/Getty Images)

“There is no doubt I inherited (my mentality) from dad,” Stokes wrote in Firestarter.

But Gerard did not reserve his disregard for professional medical opinions for himself. Speaking to the BBC in 2023, Stokes’ primary school teacher Mike Smellie recalls an important cup fixture where Stokes’ school, Plimmerton, had made it through to play the much bigger, much more fancied Palmerston North. Stokes, however, had a broken arm.

“I was asking if he could play and he said he had another three weeks in plaster,“ said Smellie, who passed away later that year. ”I rang his mum, pretending to talk about something else. We got on to cricket and she said no.

“The next day, Ben walked up the school driveway, pulling his cricket bag, with no cast on his arm. I said, ‘What’s going on?’ He said, ‘Dad got out the scissors and cut it off this morning’.”

Plimmerton lost. But Stokes made a hundred.

“He’s just a natural sporting star, isn’t he?” says Shaw, his childhood coach in Christchurch. “He turned up and wanted to excel. Other kids were there to make up the numbers, but he came to practise, to really practise.”

The square at Merivale Papanui (Cameron Ponsonby/The Athletic)

While physically no bigger than any of his contemporaries, Stokes’ power set him apart. He had the tangible qualities where adults catching a ball thrown from him, or feeding a ball for him to hit had it returned with interest. In one match as a junior, an uncut outfield meant no child on either side could manage a boundary as the ball got caught up in the long grass. Stokes was unaffected, though. He hit it over everyone.

“I remember one game (for Wellington) we played in Blenheim,” says Cameron. “And Ben decided he wanted to open the batting and no-one else put their hand up. So I thought, ‘OK, off you go Ben.’

“And he hit this cover drive that would have put David Gower to shame. And I thought blimey, if a kid 10 years of age can do that, and he can bowl a leg break and he can do this and he can do that and he can throw the stumps down from 50 metres, this kid is going to go a very long way.”

Stokes’ talents were not confined to one sport. His mother was the cricketer in the family, continuing to play while she was pregnant with Stokes. While, unsurprisingly, he was an equally fine rugby league player courtesy of his dad. Furthermore, his ability to kick with both feet, a skill trained on the countless evenings spent down the rugby club, saw him invited to trial for the New Zealand Under-16 Australian Rules Football team. He was 12.

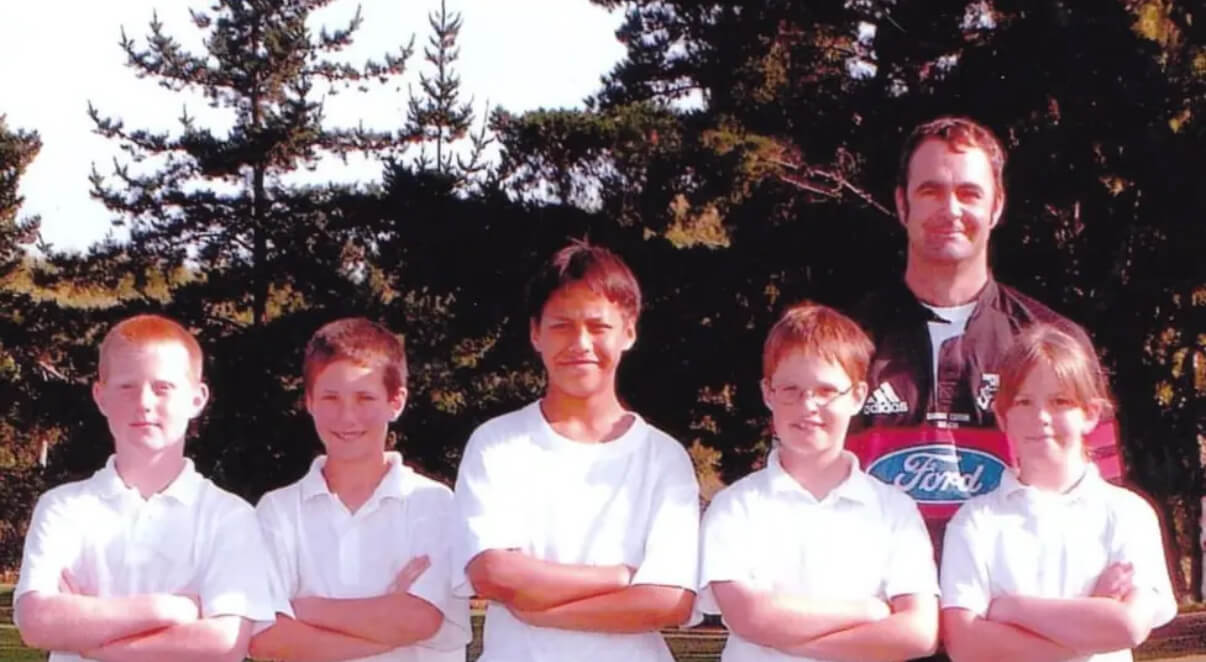

Ben Stokes, left, as a Merivale player with coach Mark Shaw, at the back (Mark Shaw)

Stokes was not alone in his youthful cricketing ability. In the two years he spent in Wellington, he was team-mates with Tom Blundell, who is now New Zealand’s Test wicketkeeper, while the other standout in his age group was a child named Harry Boam. After Stokes moved to England, the next time Stokes and Boam would meet was in the Under-19 World Cup seven years later, Stokes playing for England, Boam for the Black Caps.

In a quirk of fate, that World Cup was held in New Zealand, making it a homecoming for Stokes, who still had family in the country, and a proud moment for all who had been involved in the development of the “free-thinking” 10-year-old who had grown to fulfil his potential.

Stokes scored a century in that tournament, which came against India at Lincoln, a town that is only a half-hour drive from his childhood home in Christchurch. By coincidence, Shaw’s work had taken him to the ground that day.

“I knew the groundsman and I went down to give him a hand,” Shaw says. “And then Ben scores a hundred! So I said to the groundsman, ‘I remember that kid from way back at Merivale.’ And so he said, ‘I’ll take you to the changing rooms and you can say g’day.’

“And I went in, and he did not remember me at all,” Shaw says, laughing. “No idea. He’d just scored a hundred and I was the last person he wanted to talk to I imagine.”

A tale as old as time. The proud adult, speaking to the oblivious child.

Ben Stokes with his father Gerard Stokes and mother Deborah Stokes at Christchurch Airport in November 2017 (Kai Schwoerer/Getty Images)

To this day, Stokes’ mother still lives in Christchurch, and before the Ashes he paid a visit to New Zealand to see his family that still live on the South Island.

For the rest of the world, it was an unlikely journey. “You’d never have thought that the son of a rugby league player would end up playing cricket for England,” Shaw says.

But those closer to home saw the writing on the wall from the beginning. “I always had a feeling that cricket would win out in the end,” his father said in an interview back in 2015. “He just spent so much time developing his game.

“He was playing senior cricket when he was 13 so he was very used to the changing-room environment with adults. He grew up with men and he used to hear all the things you shouldn’t at that age.”

The sense for all those who were part of Stokes’ upbringing is pride — but not surprise — at his success. In the years after he left, news filtered back that he had made the England Under-15 team, then been signed by Durham, before ending up as the captain of his country.

“I guess you could say he was a bit of a tearaway,” Shaw says. Twenty years on and 115 Tests later, the same remains true today.