Building Britain

Featuring royal decrees, landmark social reforms and battles that changed the course of history, the years we’re about to explore are the ones that – we think – have most influenced where Britain and its people find themselves today. We’ll tell you what happened and why, and, where relevant, reveal places you can still visit today to learn more about it all.

Discover the years that have most influenced the Britain we know today…

1066: The Battle of Hastings is fought

For Brits, it’s common knowledge that the Battle of Hastings took place in 1066. This battle was won by William the Conqueror, who swiftly completed the Norman Conquest – often described as the last successful hostile invasion of England.

History buffs looking to find out more about William’s victory over Harold Godwinson, the last crowned Anglo-Saxon King of England, should head for Hastings in East Sussex. The site of the abbey and battlefield has interactive displays and audio tours to help you step back in time. At the British Museum, the famous 224-foot (68m) Bayeux Tapestry – which depicts the invasion – will be going on display in 2026.

1215: The Magna Carta is signed

Peter Phipp/Travelshots.com/Alamy

It might sound like a collaboration between ice cream makers, but Magna Carta is actually one of the most significant documents in the history of British governance. First issued in June 1215, it was the first document to put down in writing the principle that the king was not above the law.

Today, you can visit the Magna Carta Memorial at Runnymede in Surrey. This unassuming spot by the River Thames is where King John – widely memorialised as ‘Bad’ King John – signed the document that put limits on his royal power, under the watchful gaze of his barons.

1348: The Black Death arrives in England

Art Directors & TRIP/Alamy

First occurring between 1347 and 1351, with several recurrences later in the century, the Black Death ravaged 14th-century Europe, leading to an estimated 25 million deaths. Arriving in southern England in the summer of 1348, it spread rapidly through the country, with London suffering horribly in the first half of 1349. It wasn’t long before the disease had spread to every corner of the British Isles.

By the time the Black Death moved on, it had reduced Britain’s population by 30% to 40%. It wasn’t all bad news for the peasants left behind, however, as severe labour shortages followed, allowing Britain’s poorest to demand better conditions and pay.

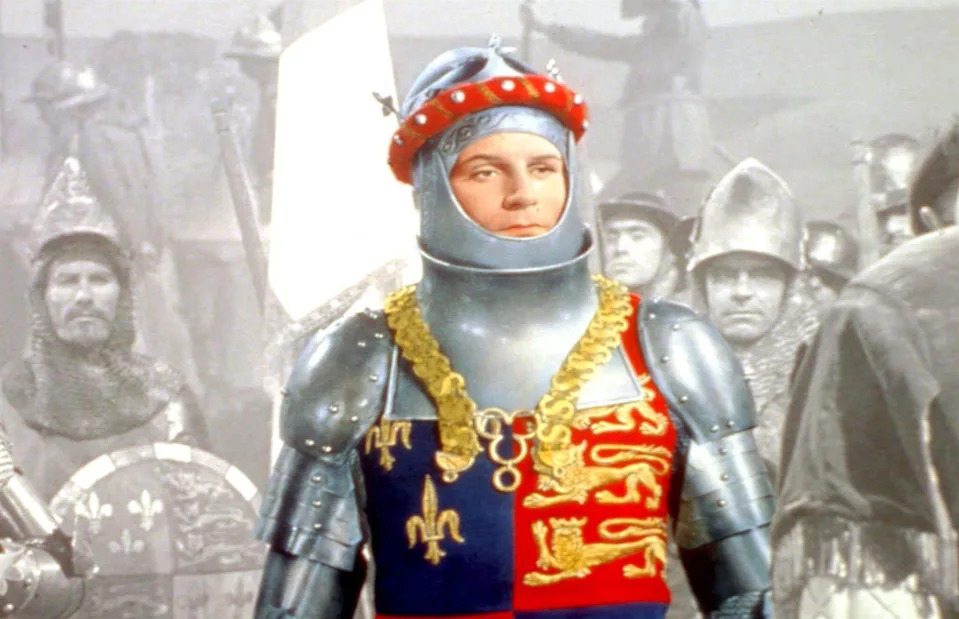

1415: Victory at the Battle of Agincourt

Historically, it’s fair to say that England and France haven’t always seen eye to eye. Back in October 1415, the Battle of Agincourt was a decisive victory for King Henry V’s English army in the long-running Hundred Years’ War. This success was famously achieved thanks to the might of the English longbow, as Henry’s archers helped him overcome a massive numerical disadvantage.

Inspiring one of William Shakespeare’s most famous plays, Henry V, Agincourt sparked a nationalistic frenzy back home, and to this day is cited as a classic English away win. You can visit the site of the bloody clash near the town of Azincourt, France.

1534: The Act of Supremacy comes into effect

Perhaps no king or queen in British history remains so talked about so long after their death as Henry VIII. Ultimately making it possible for Henry to remarry (something that, you might recall, he did more than once), 1534’s Act of Supremacy made Henry the Supreme Head of the Church of England.

The move severed religious ties with the Catholic church in Rome, fundamentally changing the nature of English religion. Learn more about the life and times of Henry VIII by paying a visit to Hampton Court Palace or the Tower of London.

1588: The Spanish Armada is defeated

North Wind Picture Archives/Alamy

When King Philip II of Spain sent his great fleet, the Spanish Armada, to invade England in 1588, there was a very real possibility of England being absorbed into the Spanish Empire. The ensuing naval battles, the first to be fought entirely with heavy guns, marked a pivotal moment in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and the history of the British Isles.

Catholic Spain invaded because of religious differences and perceived English meddling in Spanish affairs, but their effort was undone in part by poor planning and bad weather. The episode is still cited as one of England’s greatest victories, and you can learn more at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London.

1603: The Union of the Crowns takes place

GRANGER – Historical Picture Archive/Alamy

Until the early 17th century, England and Scotland existed as two independent kingdoms. This changed in 1603 when the unmarried and childless Queen Elizabeth I died. James VI, King of Scotland, was her cousin, and stepped up to become ruler of both countries.

His efforts to unite the nations into one entity were met with little enthusiasm in Westminster, but his symbolic decree in October 1604 that he would be referred to as King of Great Britain would have major implications. The order in 1606 for a British flag to be created – one that combined the crosses of St George and St Andrew – resulted in the first ever Union Jack.

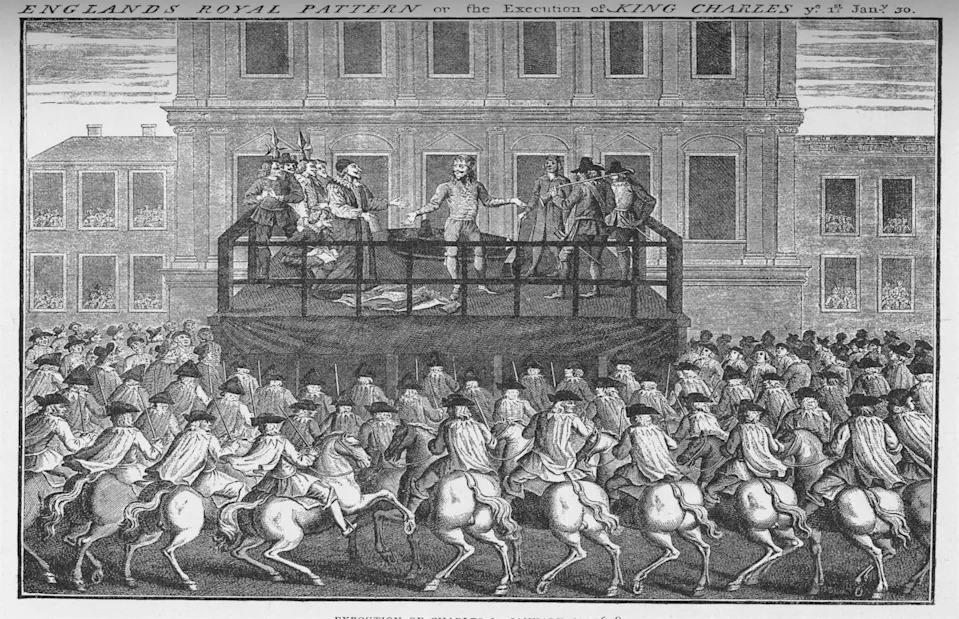

1642: The English Civil Wars begin

Heritage Image Partnership Ltd/Alamy

The English Civil Wars were a catastrophic series of conflicts that began in 1642. Fought between those loyal to the crown, then worn by King Charles I, and those loyal to Parliament, the violence tore the country apart at every level of society.

At the core of the fighting burned questions around religion and the extent of royal power. A firm believer in his divine appointment as monarch, Charles I was eventually executed outside Banqueting House in Whitehall, London, in 1649. You can learn more about this brutal period of history, and Oliver Cromwell’s subsequent decade of republican rule, at various English Heritage sites.

1666: The Great Fire of London destroys the capital

IanDagnall Computing/Alamy

On 2 September 1666, a bakery fire near Pudding Lane led to the destruction of the nation’s capital. Over the course of four days, a raging inferno swept across the city, destroying 13,200 wooden houses, 87 churches and even St Paul’s Cathedral. With their thatched roofs, London’s tightly packed homes were tinderboxes that helped the flames spread.

Remarkably, when the fire was extinguished, only six deaths were officially recorded. But with almost 85% of the city’s population homeless, the tragedy’s impact was enormous. The event is commemorated by a 202-foot (62m) column near London Bridge simply called ‘The Monument’.

1688: The Glorious Revolution changes everything

North Wind Picture Archives/Alamy

Referring to events across 1688 and 1689, the Glorious Revolution led to the exile of King James II, an overt Catholic, and the accession to the throne of his Protestant daughter Mary and her Dutch husband William of Orange. It is often cited as a landmark moment in the development of Britain’s political system.

The resulting 1689 Bill of Rights established, among other things, the principles of frequent parliaments, free elections, freedom of speech, the right of petition and the just treatment of people by courts of law. Barring Catholics from the throne and cementing Protestant dominance, its knock-on effect in Ireland was significant too.

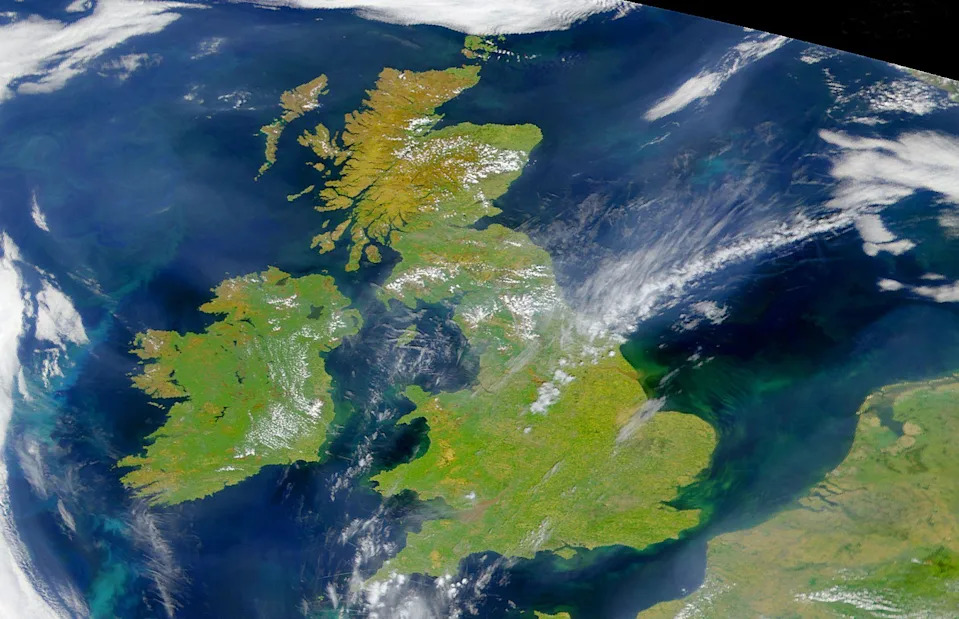

1707: The Acts of Union bind England and Scotland

Passed by the English and Scottish parliaments, the Acts of Union led to the creation of a united kingdom that would be called ‘Great Britain’. The new British parliament would meet for the first time in October 1707.

As we’ve already seen, the countries had been joined in a loose collaboration known as the Union of the Crowns since 1603. A more official coming together, though, suited Scotland’s need for economic security and England’s desire for safeguards against French attacks and Jacobite rebellions. There’s a painting of the historic event on display in St Stephen’s Hall at the Houses of Parliament.

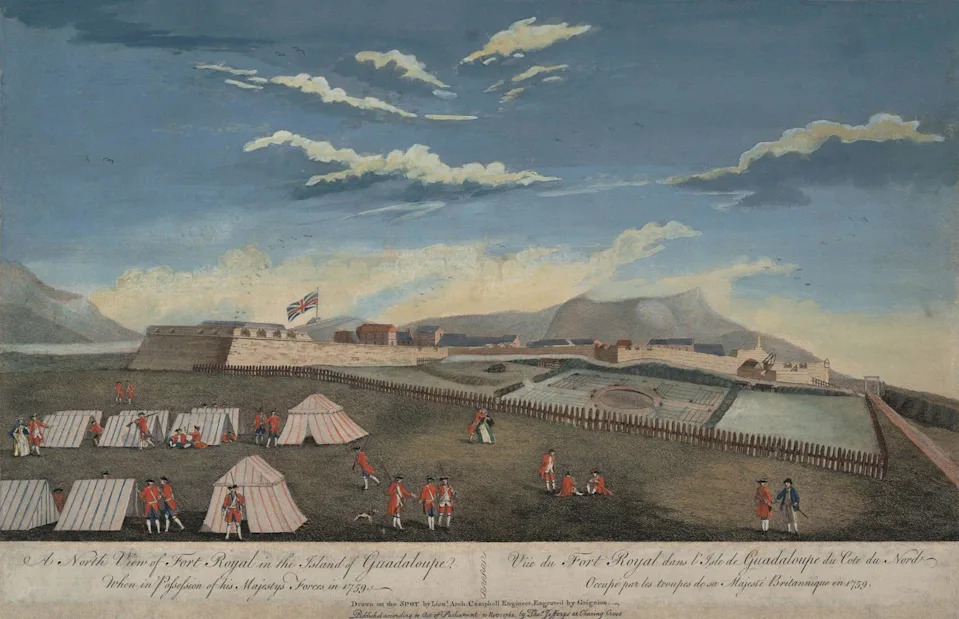

1756: The Seven Years’ War starts

Everett Collection Inc/Alamy

Between 1756 and 1763, the British fought against their old enemy the French not just in Europe but around the world. By the time the Seven Years’ War ended with the Treaty of Paris, Britain had secured almost the entire Atlantic coast of North America, and claimed territory-expanding victories in India and the Caribbean.

Trouble in North America would soon follow, but the conflict nevertheless set Britain on a path to becoming the world’s leading colonial power. In 1773, George Macartney famously described the British Empire as one “on which the sun never sets”.

1776: A Declaration of Independence

When the first shots of America’s Revolutionary War were fired at the Battles of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts, Boston, in 1775, it began a chain of events that saw Britain lose control of its Atlantic colonies. The Declaration of Independence in 1776, espousing life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, strengthened the morale of George Washington’s troops as they rebelled against the British crown.

Although the War of Independence officially continued until 1783, it was America’s formal announcement of a breakaway seven years earlier that loosened Britain’s grip. A new power had risen – and it would continue to rise.

1801: The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland is formed

The idea of an official union between Great Britain and Ireland had been tossed around since the middle of the 17th century. After the Irish Rebellion of 1798, though, and with French invasion a real threat, the British government decided to act.

Despite opposition from many Irish, the act was passed in both Dublin and London. Coming into effect on 1 January 1801, the Irish parliament was abolished and replaced with 100 representatives at the British parliament in Westminster. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was born.

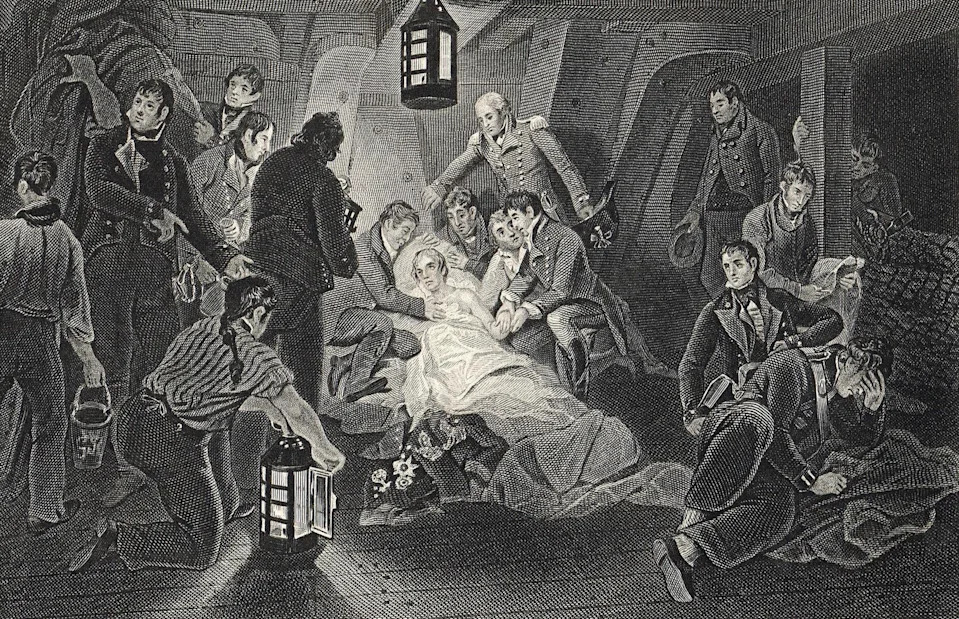

1805: The Battle of Trafalgar

Historical Images Archive/Alamy

Napoleon is famously reported to have once said, “Wherever there is water to float a ship, we are sure to find the British in our way.” By defeating a combined French and Spanish fleet that Napoleon had gathered off the coast of Cádiz, Spain, on 21 October 1805, the Royal Navy ensured that it continued that way.

Under the command of Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson (pictured), the British Fleet claimed a decisive victory at the Battle of Trafalgar without losing a single ship. The victory ended any realistic notion Napoleon had of invading Britain and confirmed Britain’s dominance of the seas for the next 100 years.

1815: The Battle of Waterloo

Just 10 years later, on 18 June 1815, the British – alongside their Prussian allies – put the final nail in the coffin of Napoleon’s European ambitions by defeating the French Imperial Army on a field near Waterloo, in what is Belgium today (pictured).

The Battle of Waterloo concluded over two decades of warfare, during which Napoleon had severely restricted British economic activity on the Continent. It also brought relative peace to the continent for almost a century – with the exception of the Crimean War (1853-56) – enabling Britain to focus on expanding and entrenching its empire.

1832: The Reform Act expands voting rights

As the 19th century marched on, Britain’s ruling class struggled to shake the blood-soaked memory of France’s violent revolution in 1789. The aristocracy were fearful of a repeat of what had happened across the Channel, and Britain’s electoral system had obvious problems: a limited number of people with the right to vote, unequal seat distribution and the notorious ‘rotten boroughs’ – a borough with only a few voters but with the right to send a representative to Parliament.

The Reform Act of 1832 created new seats for MPs and allowed more middle-class men to vote. Although the changes themselves were limited, it showed that change was possible, sparking further calls for parliamentary reform.

1851: The Great Exhibition celebrates Britain’s strength

Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

Thought up by Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria, the Great Exhibition was a chance for the world’s finest inventors and scientists to show off their work. Many countries were represented at the show in London’s 1,847-foot-long (563m) and 407-foot-wide (124m) Crystal Palace, but it was certainly the host nation making the biggest statement.

Boasting over eight miles (12km) of displays, six million people visited the structure in six months. Standout attractions included the Koh-i-noor, the world’s largest diamond. The glass-and-iron building burnt down in 1936 after moving to South London in 1854, but its ruins remain in Sydenham to this day.

1914: The first shots of World War I are fired

Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

When Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was assassinated in Sarajevo in June 1914, it set off a chain of events that led to a war unlike any the world had ever seen. By the time the fighting stopped on 11 November 1918, the lives of over 10 million soldiers had been lost.

In Britain, industry, technology and the civilian population were all mobilised on an unprecedented scale. In total, around five million Brits – a mix of volunteers and conscripts – saw combat. Pay a visit to London’s National Army Museum and Imperial War Museum to find out more.

1928: The Equal Franchise Act gives women equal voting rights

Today, it seems astonishing that less than 100 years ago women did not have equal voting rights to men. Some women were given the vote in 1918, thanks to the tireless efforts of several suffrage movements, but it would take another 10 years before full voting equality arrived.

The Equal Franchise Act meant both men and women could vote at the age of 21, which inadvertently made the latter the majority of the electorate (women comprised 52.7% of potential voters). Check out the Pankhurst Museum in Manchester to find out more about a political movement that transformed British democracy.

1939: Britain enters World War II

Fought across most of the world between 1939 and 1945, World War II claimed the lives of between 40 and 85 million people (estimates vary greatly). It remains the largest and bloodiest war in human history by some margin.

Barely two decades after the end of World War I, Britain again found itself pulled into the fire – with Prime Minister Winston Churchill adopting a ‘never surrender’ policy in the face of Nazi aggression. Today, hidden beneath Westminster, the Churchill War Rooms give you the chance to wander the secret underground headquarters the British war effort was directed from.

1948: The National Health Service is founded

World History Archive/Alamy

On 5 July 1948, the National Health Service was established, making Britain the first western country to offer medical care to its entire population that was free at the point of use. Pictured here, Aneurin Bevan, the Labour government’s minister of health and an instrumental figure in the NHS’s origin story, can be seen touring a hospital near Manchester.

In recent years, the service’s frontline staff were lauded for their courage during the COVID-19 pandemic. To learn more about the history of healthcare in Britain, get on down to Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries at the Science Museum in London.

1966: England win the FIFA World Cup

Football is sometimes called “the most important of the least important things”. And the massive reaction that greeted England’s World Cup win in 1966 (with apologies to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) might prove the saying true.

Taken after the 4-2 win in the final against West Germany at Wembley Stadium, this shot of captain Bobby Moore holding up the Jules Rimet trophy is, for the English, one of the most iconic images of the 20th century. Almost 60 years on, England’s men are still trying to win another major tournament. Visit the National Football Museum in Manchester to explore the nation’s love of the beautiful game.

Now check out historic photos of the sporting moments that shook the world