The soaring cost of living has become Greece’s defining national pressure point. Grocery bills, rent hikes and stagnant wages dominate everyday conversations and consistently return to the center of political debate. And while political leaders battle it out in Parliament over inflation and affordability, new data shows just how deeply this problem is felt.

And while political leaders battle it out in Parliament over inflation and affordability yet again, Greece ranks first in what Eurostat calls subjective poverty — how individuals perceive their own financial and material situation.

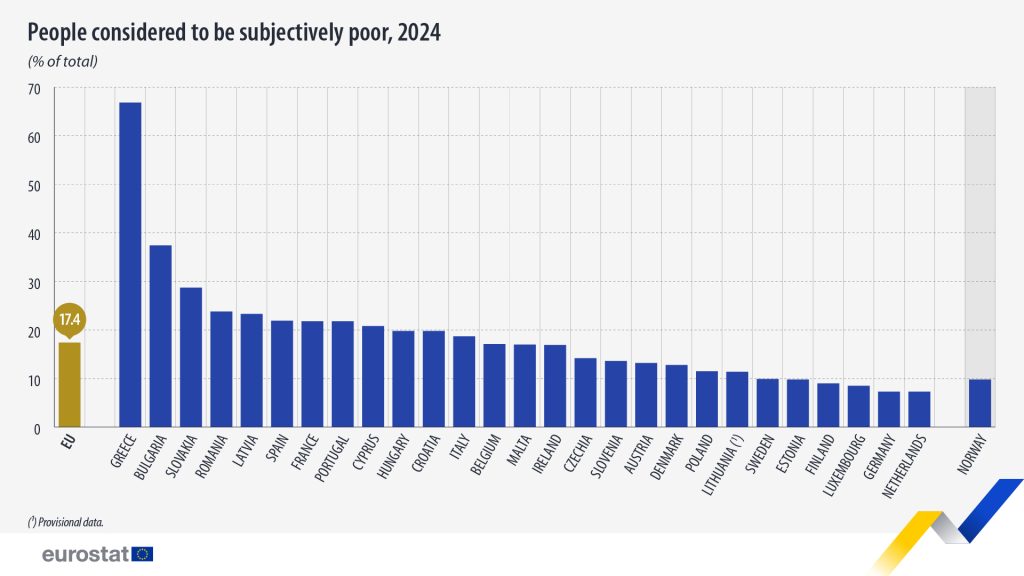

Nearly seven in 10 Greeks (66.8%) say they feel poor. It is the highest rate of subjective poverty in the European Union, where the average stands at just 17.4 percent.

As shown in Eurostat’s 2024 chart on subjective poverty, Greece records by far the highest rates in the EU.

What does it actually mean when such a large part of Greek society feels poor?

According to Gerasimos Prodromitis, professor of social psychology and Vice-Rector for Administrative, Student Affairs and Digital Governance at Panteion University in Athens, this feeling amounts to “an absence of hope — a lack of positive expectation and outlook.” It is, he told the newspaper To Vima, “an explosive mix which, on a psychological level, creates individual feelings of frustration, possibly low self-esteem and depressive withdrawal, but also more active (and possibly activating) emotions of anger and rage.”

In the Eurostat chart, the gap between Greece and the other EU member states becomes clear. Greece’s rate is almost four times the EU average of 17.4 percent in 2024.

“This figure reflects the widespread sense of economic hardship in Greek households, which is much higher than what is indicated by the data on the poverty threshold or even on the risk of poverty and social exclusion,” said Marianella Kloka, president of the board of the Greek Network for the Combat of Poverty.

The Gap Between Greece and Europe

Far behind Greece comes Bulgaria, at 37.4%, followed by Slovakia, at 28.7%, whereas in the Netherlands and Germany, the rate is just 7.3%. In other words, the share of Greeks who say they feel subjectively poor is nearly twice that of second-place Bulgaria, and eight times that of the Dutch and the Germans.

“The index of relative poverty concerns the relative deprivation of the population that is at risk of poverty, or faces material and social deprivation, or lives in households with low work intensity, as defined by experts,” explains Giorgos Loukas, a social worker and board member of the Hellenic Association of Social Workers (SKLE), speaking to To Vima.

This huge gap underscores the fact that in Greece, economic insecurity and a broader sense of precariousness remain strong.

The Imprint of Repeated Crises

The issue of subjective poverty is not purely economic. It also has social and political dimensions.

As Prodromitis observes, contemporary societies are marked by individualism. “In a society fragmented into individuals,” he says, “all this corresponds to an internalization of the TINA syndrome (There Is No Alternative). It is expressed as a trapped withdrawal into one’s private microcosm and as a displacement of aggression onto others, as a consequence of deprivation.”

Greek society, in the aftermath of the crisis that began about 15 years ago, appears to be living in a continuous and generalized state of “subjective poverty.” This feeling is linked to the deprivation of economic and social goods within a long-lasting condition of multiple crises. As Loukas points out, “This index expresses the real needs of the country’s population and the impact of the multiple crises that followed one another.”

This web of successive crises from 2008 to today seems to be inscribed in the psyche of Greek society. It is also telling, Prodromitis notes, how “subjective poverty” can be viewed through the lens of social psychology.

“Across the successive crises,” he says, “Greeks collectively felt what social psychologists call ‘relative deprivation’ — the sense that the opportunities for upward mobility had essentially disappeared, even in theory. People no longer felt they could count on a better future or enjoy the small, everyday comforts they once took for granted. This creates a personal sense of bitterness and injustice: the feeling that you are not receiving what you believe you deserve, especially when you compare yourself with others or even with your own past.”

This raises a logical question: why hasn’t this widely shared frustration produced broader social movements or collective demands?

Prodromitis notes that feelings like these often lay the groundwork for collective action; they are what typically precede organized demands for change. But today’s social landscape — fragmented, individualized and inward-turning — makes it far harder for that frustration to coalesce into a broader movement.

Europe Moves Ahead, Greece Stays Behind

Across the EU, the share of people reporting severe difficulty covering basic expenses fell in 2024, from 9.1% in 2023, to 17.4% in 2024. But Greece continues to lag. The country ranks second-to-last in income levels in the EU, just above Bulgaria.

There are also significant geographical differences between EU countries. In northern and western Europe, rates are low (around 7–8 %), while in southern and eastern Europe they are significantly higher (20–37%).

As noted earlier, in Greece’s case Eurostat’s data reflects deeper economic and social factors. First and foremost, wages and incomes are on average much lower than in most EU countries, while the cost of living and specifically the cost of energy, housing and food is fiarly high.

“In the past we used to say that low wages were justified because our country had a low cost of living,” Kloka says. “This is no longer true, and we all experience it in the supermarket, we see it reflected in rental prices and unpaid electricity bills, mobile phone bills and loan installments.”

Why Greeks Feel So Poor?

Loukas offers insight from the front lines of social work, describing the reality he and his colleagues confront every day.

Loukas describes what social workers see every day: a growing number of adults and children who are losing access to services and protections that should be basic guarantees. Many struggle to secure housing, health care, safety, or education, and they increasingly turn to social services for urgent assistance. “The rising cost of living. from food and energy prices to rents and mortgage payments, has created a suffocating reality for families and households across the country” Loukas underscores.

The OECD notes that housing prices in Greece have risen by 69% since 2017, a much greater rate of increase than wages. As a result, 27% of households now spend more than 40% of their income on housing costs, a share that is four times the European average of 9.4%.

This suffocating pressure is reflected directly in the subjective feeling of poverty.

Access to basic public services in Greece — health care, education, transportation — is often complicated and unreliable, a reality that deepens the feeling of social marginalization. Research shows that when people measure their daily lives against the standards they believe should be normal, or when they struggle to secure essentials like a doctor’s appointment or dependable public transit, their sense of poverty intensifies.

In this sense, Greece’s prolonged financial and social crisis has significantly affected citizens’ everyday experience and expectations.

Even as the broader economy appears to rebound, many Greeks say the recovery has bypassed them — a sentiment reinforced by the persistent financial insecurity facing large parts of the population.

The index of subjective poverty captures something different from the usual economic data that measure who is formally at risk of poverty. It reflects a broader sense of vulnerability — a feeling of being unable to cope — that is tied not only to income but also to psychological strain and the wider social and political environment.

Kloka notes that research links this sense of insecurity to rising risks of depression, other mental health conditions and even addictions, including alcohol, drugs and gambling.

Greece’s situation is further exacerbated by long-standing inequalities: low wages and pensions, a tax system that weighs heaviest on those with the least and housing costs that continue to climb.

Women and Young People Feel Poorer

Subjective poverty varies across demographics. Women report slightly higher levels of financial insecurity than men (17.8% versus 17.0%). Young people under 18 feel the most vulnerable (20.6 %), while older adults over 65 feel it least (14.9%).

Education matters too: people with lower educational attainment are far more likely to say they cannot make ends meet (27% versus 8.5%). Unemployed individuals feel the highest level of insecurity (42%), followed by non-working adults(24.7 %). Only a minority of employed people (13.5%) or pensioners (14.2%) report severe difficulties, though the numbers are still significant.

This comparison shows that beyond income, living standards and the overall quality of life matter. For example, German or Dutch citizens with middle incomes enjoy a high standard of living and benefit from a stronger social safety net and a more reliable system of public support.

The Poverty Risk That Lurks

More than 2.74 million Greeks -26.9% of the population- are at risk of poverty or social exclusion. This group includes many families with children (with child poverty close to 22.4%), young people entering the workforce with only a high school diploma, older unemployed adults and even full-time private-sector workers.

In countries with stronger welfare systems, people in similar situations do not feel the same pressure. In Germany, for instance, low-income families often receive direct financial assistance or can access loans on favorable terms, easing the strain on household budgets.

Steps Toward Change

Can subjective poverty become a catalyst for social or political change?

Prodromitis thinks it can. This widespread sense of deprivation, he argues, could prompt people to question the power structures that shape economic life and push them to demand something more humane and equitable.

But in the economic sphere, a disconnect remains. Political leaders speak of “growth for all,” yet many citizens see little evidence of it in their daily lives. The real question is whether any of that growth will actually reach them, and whether the relentless rise in prices can be contained enough to ease the feeling of poverty.

Kloka argues that meaningful relief will require concrete steps: adjusting wages and pensions to inflation, lowering the standard 24% VAT rate, removing VAT altogether from basic food items and reforming a tax system that currently places the heaviest burden on those with the least. She adds that rent levels, supermarket prices and energy costs all need tighter oversight. Such measures, she says while talking to To Vima, would give households room to breathe and allow other public systems, including education and health care, to function more effectively.

Loukas offers a similar view. To change course, he says, policy must put people at the center rather than focusing solely on macroeconomic indicators. That means strengthening the incomes of those living below the poverty line and ensuring real access to essential rights such as housing, health care and education.

Breaking the cycle of widespread subjective poverty will require a strategy that makes a tangible difference in people’s daily lives — something they can feel, not just see reflected in national statistics.