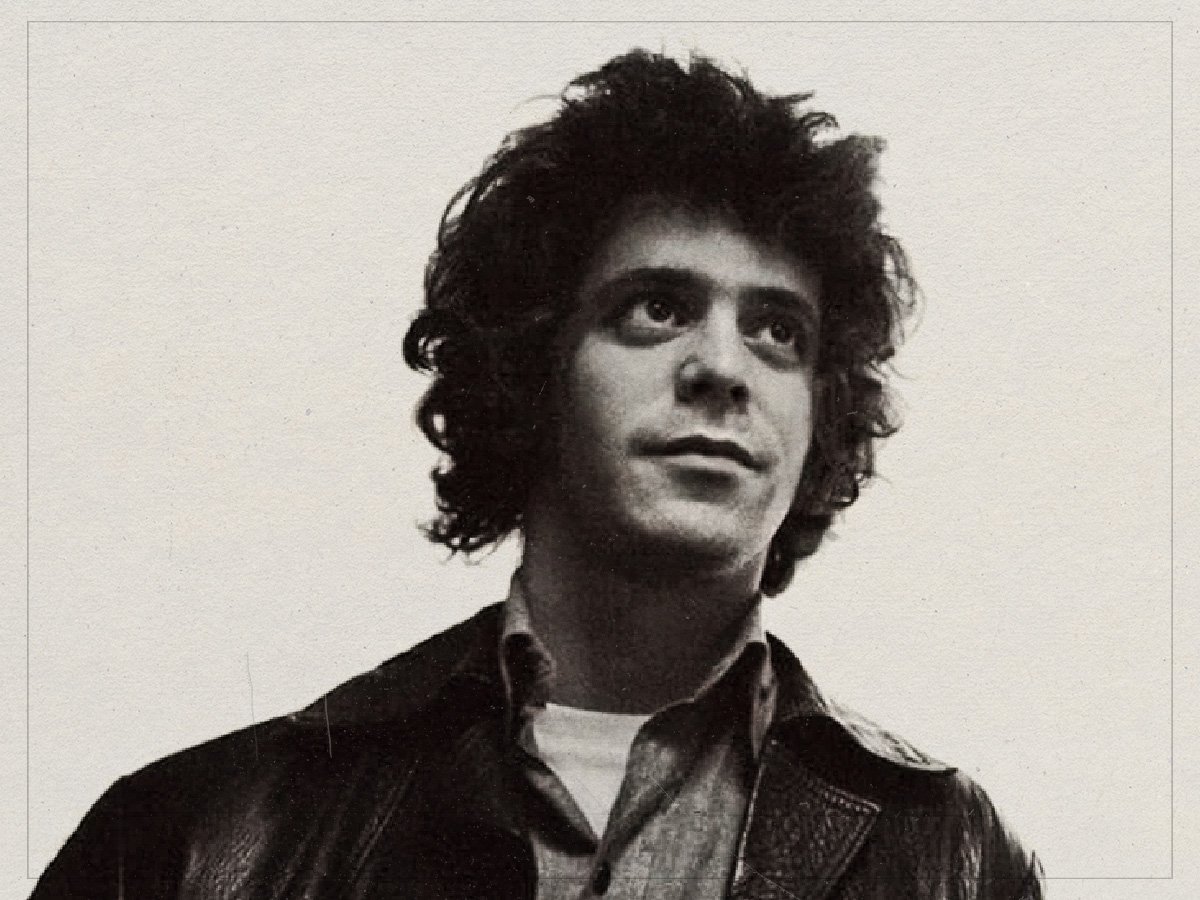

(Credits: Far Out / Album Cover)

Sun 16 November 2025 19:45, UK

Lou Reed was a man of few words—in conversation, that is.

An infamous persona followed Reed from when he first tasted fame in the early 1960s with The Velvet Underground. He had little to no tolerance for interviews, often coming off as detached and easily provoked to anger and scorn. His demeanour was dominated by a face that rested somewhere between solemn and boredom, speaking with a cool remove. He was both shy and confident, resolving to tact when there was nothing else to say.

Yet, on record, he was an open book.

To sing brazenly on ‘Heroin’ of the gory intricacies of his drug use and of sadomasochistic themes on ‘Venus in Furs’, while remaining resigned face-to-face, only added to Reed’s intrigue. With his departure from The Velvet Underground in 1970, Reed’s solo career warranted deeper introspection in his songwriting: a rare glimpse at Reed, unmasked.

He continued to sing of sex and drug use, while also chronicling the dark underbelly of city life and its eccentric, shady cast of characters, never shying away from transgression. Reed’s stories often held up a mirror to himself; we could hear bits of himself woven into his tales of friends, lovers and acquaintances who crossed his path. But sometimes, Reed directly confronted himself, writing tragic stories of a life burdened by addiction and struggle. One song in particular tells of his life pre-fame, when his teenage years were spent in a torturous psychiatric hospital: ‘Kill Your Sons’.

In 1959, during his first year of college at New York University, Reed was brought home to Long Island after suffering a mental breakdown. As writer Will Hermes describes in his biography of the musician, Lou Reed: the King of New York, Reed remained “depressed, anxious, and socially unresponsive” for a period of time.

(Credits Far Out / Faber & Faber)

(Credits Far Out / Faber & Faber)

Encouraged by a psychologist, his parents consented to having Reed undergo electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), thrice weekly for eight weeks. Reed said later that his parents sought to “cure” his suspected homosexuality, though his depression and subsequent behaviour are cited as the primary reasoning. It is an experience that haunted Reed for the rest of his life, and one that he immortalised on ‘Kill Your Sons’.

Appearing on 1974’s Sally Can’t Dance, ‘Kill Your Sons’ calls out Reed’s parents and the “two-bit psychiatrists giving you electro shock”, sung with a spitting voice that amplifies Reed’s signature drone. He also chronicles the therapy’s after-effects, particularly the memory loss he endured. “But everytime you tried to read a book / You couldn’t get to page 17,” he sings, “‘Cause you forgot, where you were / So you couldn’t even read.”

He names the hospitals he was admitted to – ”Creedmore treat me very good / But Paine Whitney was even better” – and of the drugs he was administered on top of his ETC treatments, producing a range of emotions. With a dark humour, he sings, “All of the drugs that we took, it really was lots of fun / But when they shoot you up with thorizene on crystal smoke / You choke like a son of a gun.”

Reed’s blatant criticism of his family continues, with a particular scathing tone towards his father. He sings of his Mom calling him on the phone, informing him of his father’s violent behaviour: “Took an axe and broke the table,” Reed recalls dryly. “Aren’t you glad you’re married?” he follows, with an almost mocking tone.

Reed’s sister, Merrill, on the other hand, married and stayed on Long Island. Her husband, as Reed recounts, is “big and he’s fat, and he doesn’t even have a brain”. From Reed’s point of view, his native Long Island has become a place of stagnancy, one with too much trauma to endure. He equates the island with his family and regards both with disdain, complicit in his wrongful treatment.

As the chorus repeats, “Don’t you know they’re gonna kill, kill your sons? / Until they… run away,” Reed emphasises the ill-fated effects of his so-called therapy: the attempted killing of his old self, to reinvent anew, with his permanent aversion to the conformity that was attempted to be placed on him.

As heart-wrenching as ‘Kill Your Sons’ is to listen to, Reed allowed the song to purge his emotions on the subject, even once managing to joke to his biographer, Victor Bockris, “It was shocking, but I was getting interested in electricity anyway.”

Related Topics