The mantra of polarised training is ‘go easy or go hard – never in between’. But what if that’s all wrong? Rob Kemp meets the coach who says the middle is where the magic happens

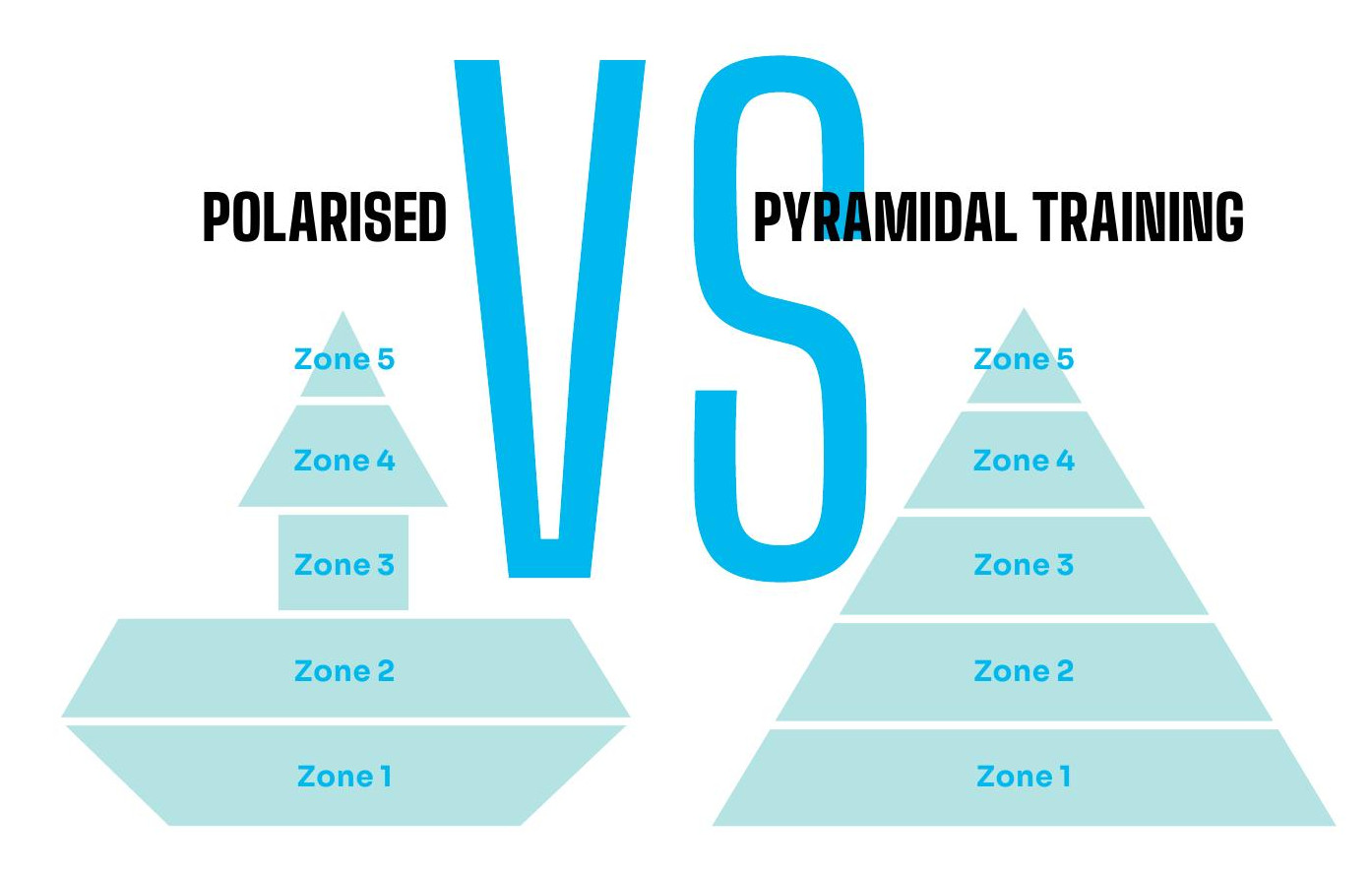

For more than two decades, polarised training has dominated endurance sports. The model – popularised by physiologist Stephen Seiler – demands that athletes spend about 80% of their training at low intensity, and 20% at very high intensity. Anything in the middle, the theory goes, is no man’s land: too hard to recover from, too easy to stimulate real adaptations.

It’s a simple, compelling message – especially in an era obsessed with data purity and perfect zone distribution. But what if everything we thought we knew about how to divvy up our effort across the week was wrong?

Best picks for you

Tempo training is the key to real-world endurance

(Image credit: Unknown)

Steve Neal, a Canadian coach with 37 years in endurance sport, doesn’t believe in a single “one-size-fits-all” model. Instead, he adapts training to the season and the athlete’s specific needs – sometimes pyramidal, sometimes polarised. The key, Neal says, is selecting the right method to move fitness in the desired direction.

While pyramidal training often emphasises tempo and so-called “middle” intensities, Neal doesn’t view this mid-level work zone as wasted effort. Used correctly, it can be the engine room of real-world performance.

“WHEN I LOOK AT RIDERS’ DATA, WHAT I OFTEN SEE IS PYRAMIDAL TRAINING I OFTEN SEE NOT POLARISED”

Steve Neal, Canadian coach

“I’ve been doing this for a long time, and whenever I look at riders’ data – whether it’s in TrainingPeaks, INSCYD, or Xert – what I often see is pyramidal training, not polarised,” Neal says. “People talk about 80/20, but in reality, when you analyse it properly with power data, my athletes are often at more like 95/5. Even when they’re racing stage races, doing two-and-a-half to three hours a day for a week, they very rarely break 90/10.”

If Neal is right, the implications are huge. Most of us might be telling ourselves we’re doing polarised training while actually implementing a structure with a broader base, heftier middle and much sharper tip – better described as pyramidal. Even at pro level, the roots of the polarised model may be shakier than most realise.

(Image credit: Photos ANDY JONES & ANDREW SYDENHAM)

Neal’s approach blends old-school coaching wisdom with new-school ideas. His mentor Juerg Feldmann, a Swiss speed skater who later coached Canadian mountain bike world champions and Olympians, taught him to combine rigorous fundamentals with innovative methods. “Some of the methods I learned from Juerg years ago are only just being discussed widely today. For example, respiration [breath] training – he was using it over 30 years ago.”

Neal has built on these innovative foundations. Unlike many modern coaches, he doesn’t take training software outputs at face value. “I think software does a great job of the higher-intensity training zones, but I still prefer to use lactate testing to dial in the training below threshold.”

At the heart of Neal’s philosophy – and his success in raising the performance of elite riders across varied disciplines – is pyramidal training. He has found that this approach especially suits athletes aged over 40, who make up 95% of his coaching clients.

At its core, pyramidal training means plenty of easy endurance work, a solid dose of tempo or “middle” intensity, and just a small amount of hard effort at threshold or VO2max. Picture a pyramid: a wide aerobic base that narrows as intensity rises, with that middle zone getting real attention.

Unlike more strictly polarised models, pyramidal training doesn’t avoid the “grey zone” – it makes smart use of it.

Neal’s cyclists use pyramidal training to build aerobic durability and fatigue resistance, improving their ability to ride at or near race pace for extended periods. “The key,” Neal says, “is looking at the actual intensities that will drive performance. Many riders and coaches neglect to consider this, and instead train in zones that look right on paper but don’t match what racing actually demands.” He points out that in stage races and Gran Fondos, riders often spend hours at tempo, which for Neal sits within Zone 3.

(Image credit: Unknown)

He defines his zones by heart rate (see box), refined with lactate, metabolic, or muscle oxygen testing where possible. When he prescribes pyramidal training, the focus is on Zone 2a/2b endurance and Zone 3 tempo, with just enough high intensity to maintain race readiness. This differs sharply from polarised training, which avoids tempo almost entirely. “One of the biggest misconceptions is that Zones 2 and 3 are fundamentally different,” Neal explains. “They’re not – it depends on the person.

That’s why I measure LT1, LT2, and a point in between that I call the ‘balance point’.” That balance point, he says, can shift dramatically even when the thresholds themselves barely move. “Sometimes I only move an athlete’s LT1 or LT2 by five watts across a whole season, but that balance point can shift by 30 or 40 watts – and that’s what makes people faster.” In other words, the athlete’s usable range of performance expands, and they are able to ride at closer to threshold (LT2) for longer periods of time, even if the threshold itself doesn’t move.

Have we been getting it all wrong?

For Neal, the entire polarised model rests on a methodological error. “Polarised training was studied at the elite level in rowing, running and cycling – but only using heart rate,” he says. “The problem is, heart rate is usually a zone lower than power.” He alludes to the fact that heart rate doesn’t always match how hard the legs are pushing: it lags behind changes in effort, and drifts with fatigue or heat.

“So those studies probably just showed what we now call pyramidal training. That’s why I think comparing pyramidal and polarised is misleading – because most of what we think we know about polarised is wrong. What I really notice in my athletes isn’t a lack of low-intensity work, but that the supposed 15–20% above threshold just isn’t there.” That’s a bold claim, but Neal has evidence on his side. Analyse a year of training from almost any serious rider, he says, and you’ll find pyramidal, not polarised, distributions.

“Even elite athletes people assume are polarised are actually pyramidal if you track them properly.”

So what does pyramidal training actually achieve? Neal points to three key adaptations. First, aerobic development: by training near the balance point, where fat and carbohydrate contribute in roughly equal measure, riders can push their aerobic system to become more efficient. Second, durability:

“If I can get someone’s tempo power closer to 75% of their VO2max power, they will race better,” Neal says. “Even if their VO2max number drops slightly, their ability to sustain power over time improves dramatically.” Finally, metabolic efficiency: riding long at tempo teaches the body to manage fuel better, delaying fatigue.

TRAINING ZONES

As defined by Steve Neal

- Zone 1: Recovery

- Zone 2a: Endurance, 60–70% max HR

- Zone 2b: Steady endurance, 65–75% max HR

- Zone 3: Tempo, or “lactate balance point,” 78–83% max HR

- Zone 4: Threshold, 85–90% max HR

- Zone 5: VO2max, 90–95% max HR

- Zone 6: Sprint/ torque efforts

The gains may not show up as flashy VO2max increases, but they win races. “If someone has a VO2max power of 350 watts, I don’t want only their five-minute power to go up,” Neal explains. “I want their tempo or balance point to be 75% of that, i.e. around 262 watts. If it was 220 watts to begin with, and I can move it up by 40 watts, they’ll race faster – even if their VO2max power drops.”

Who benefits most from pyramidal training? Neal says masters athletes with limited hours see huge gains. “One of my riders is 45, Canadian marathon MTB champion, always top three in cross-country,” he says. “Over a year, his threshold has gone from 300 watts to around 310–320. That might not seem huge, but year after year, at his age, still winning – it’s massive.”

Neal gives a UK example: Sam, a new dad, working full-time, training just eight to nine hours a week. For two years he stuck with endurance and tempo, and became rock-solid. “He could sit at 300 watts in Zone 3, breathing steady, heart rate under 83%, and call it easy. That’s durability. That’s why pyramidal training works.”

The risk, Neal cautions, isn’t just overtraining, it’s focusing too much on threshold work without balance. “Simply piling on threshold sessions doesn’t actually improve threshold,” he explains. Done to excess, or executed poorly, that kind of training can also push an athlete toward being overly glycolytic, eroding their ability to go long and ride strong in the tempo zone. Research has shown that excessive threshold work can blunt gains at that intensity. Instead, riders should build fitness at sub-threshold, says Neal, pushing the ceiling up from below.

Middle-intensity rides bring your threshold up from below

(Image credit: Unknown)

Holding back requires patience and discipline. Some riders simply find pyramidal training boring, concedes Neal, recalling a talented UK rider who improved 8-10% in three months on his system – but quit because he didn’t want to skip smash-fest group rides.

Making middle-intensity training part of the weekly schedule is nonnegotiable for Neal – it’s where performance is built. The easy miles keep you steady; the all-out efforts sharpen you. But the work that makes you faster, stronger, and harder to crack? That happens in between.

After two decades of polarised orthodoxy, that idea may feel heretical. Yet the data – and the riders – keep proving him right. The truth is that real-world cycling isn’t tidy or binary; it’s a continuum of effort, fatigue and adaptation. Somewhere between too easy and too hard lies the zone that holds it all together – not a grey area, but gold.

More middle ground worked wonders for me

An early block of pyramidal training can build the base for later success

(Image credit: Unknown)

Cameron Nicholls, 41, from the Sunshine Coast, Queensland, Australia recounts how switching from polarised training to a more middle-heavy pyramidal model paid dividends.

“I used to turn my nose up at sweetspot training. I was strictly team Zone 2 and high-intensity, plus VO2max and big-gear efforts. Nothing in the middle. I spent most of my training at low intensity and the rest in the hurt locker.

“After deciding to try something new, I worked with coach Ryan Thomas and adopted a hybrid approach. The first six weeks were pyramidal, and the remaining six weeks were polarised. In the first six weeks, I was mainly doing Zone 2 rides and sweetspot efforts, sitting in the grey somewhere between Zones 3 and 4.

“Coming from a polarised model, it was not a training philosophy I had considered. But ‘no man’s land’ wasn’t as bad as I thought. In the remaining six weeks, we ramped up the intensity and added VO2max and anaerobic HIIT sessions. My bread-and-butter Zone 2 rides were always maintained.

“At 41, I achieved personal bests in three of four key power-to-weight segments, and I had great racing results. Whether the pyramidal approach or the hybrid model takes the credit, I can’t say for sure. But it’s the only thing I really changed in the last 10 years. It delivered some of the best results of my career.”

PYRAMID IN PRACTICE

So what does pyramidal training look like in practice?

● Base phase: Lots of Zone 2 endurance, with controlled amounts of Zone 3 tempo.

● Build phase: For a rider training around eight hours per week, aim to lift tempo volume to three to four hours weekly, while keeping maintenance doses of high intensity every week or two. Depending on the athlete and the demands of their target event, this phase may also involve backing off some tempo in favour of more endurance work, or shifting focus towards race-specific intensities.

● Race season: Hold the pyramidal distribution, layering in specific intensity for events.

● A typical week for an 8-10-hour amateur might include:

– 2-3 steady endurance rides (Zones 2a/2b)

– 2 tempo sessions (Zone 3, 45-90 minutes)

– 1 group ride or race-specific session (touching Zone 4/5)

– 1 easy spin or recovery ride

● Regular testing is crucial, Neal insists. “Many of my athletes own a lactate meter and/or a muscle oxygen sensor,” he says. “Home testing helps them track where they’re at while saving money on lab sessions.”