This discovery marks the first confirmed observation of a CME beyond our solar system. It was made possible through the combined use of the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton space observatory and the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR) radio telescope. The findings highlight the significant space weather risks posed by red dwarfs, the most common type of star in our galaxy, and have important implications for the search for life beyond Earth.

First-Ever Detection of a CME from Another Star

For decades, astronomers have suspected that CMEs, massive expulsions of plasma from a star’s corona, occur on other stars, much like those seen on the Sun. However, until now, there has been no direct confirmation of a CME from any star outside of our solar system. According to Joe Callingham from the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON), previous findings had only suggested their existence, without definitive proof that material had fully escaped a star’s magnetic field.

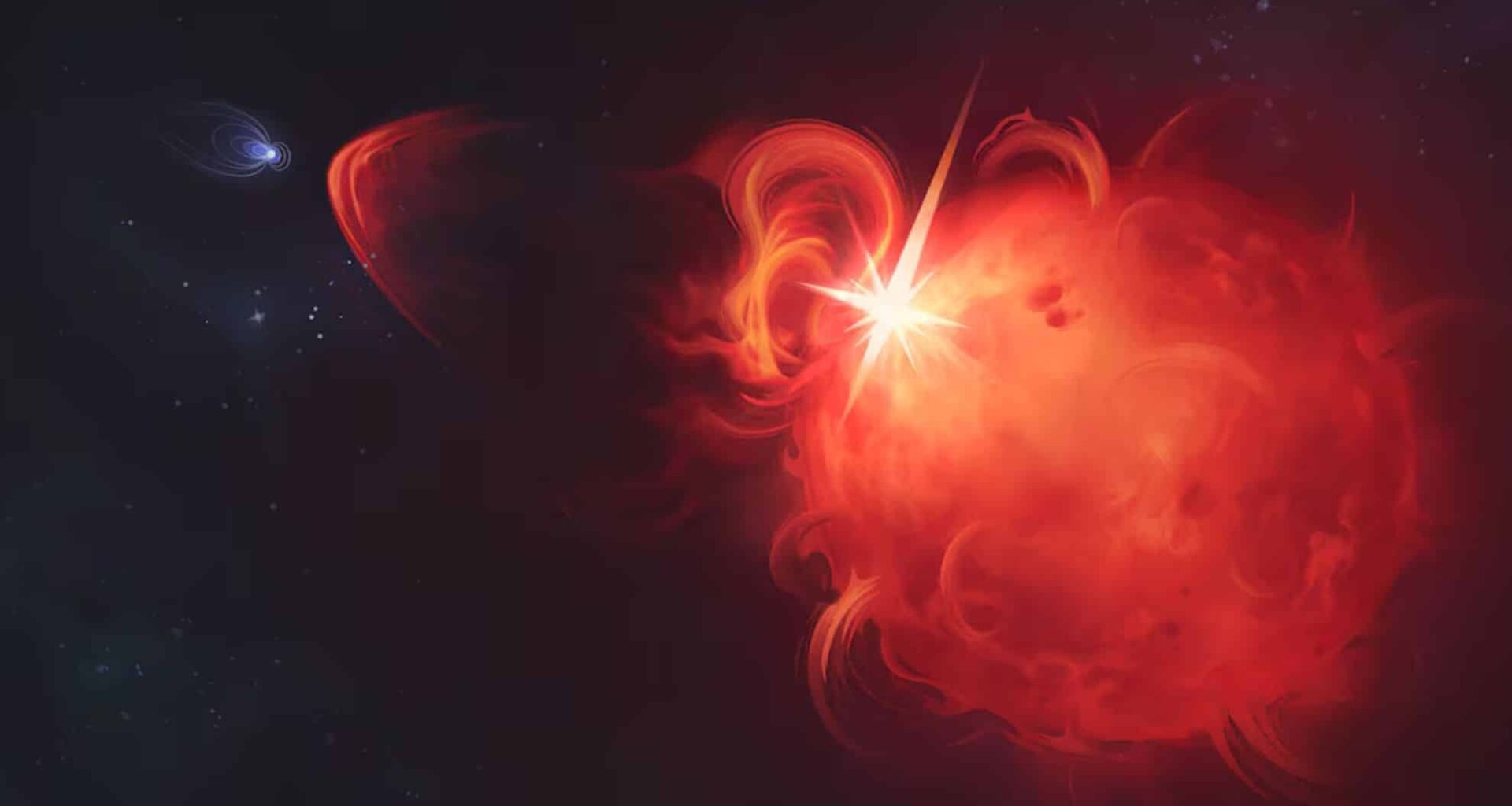

The CME was detected using LOFAR’s advanced radio capabilities, which are ideal for picking up the short, intense radio signals associated with these kinds of outbursts. The team then confirmed the eruption’s origin with XMM-Newton, which provided essential data on the star’s temperature and magnetic properties. This combination of technologies allowed researchers to trace the violent burst back to the red dwarf star, StKM 1-1262, located 130 light-years away.

Stellar Outbursts with Devastating Power

The CME observed from StKM 1-1262 is not just a typical solar flare; it was moving at an extraordinary speed, around 2,400 kilometers per second (1,491 miles per second), a pace that is seen in only 1 out of every 2,000 CMEs on our Sun. This eruption was so intense that it could easily strip the atmosphere off any nearby planet, even those within the star’s habitable zone. According to Callingham, the blast was dense and fast enough to cause serious harm to any planet caught in its path, possibly rendering it uninhabitable.

Red dwarfs, such as StKM 1-1262, are smaller and cooler than our Sun, but they are also much more active. These stars have magnetic fields up to 300 times stronger than the Sun’s, and they rotate much faster, 20 times more quickly. Such activity is common among red dwarfs, and as a result, they regularly emit powerful flares and CMEs. These extreme space weather events pose a particular risk for exoplanets that may orbit within the star’s habitable zone, where conditions could otherwise support liquid water.

Implications for the Search for Habitable Worlds

This discovery raises important questions about the habitability of exoplanets orbiting red dwarfs, which are the most common type of star in the Milky Way. These stars are known to host many Earth-like planets, making them prime candidates for the search for extraterrestrial life. However, the frequent and intense CMEs produced by red dwarfs could severely affect the atmosphere of any nearby planet, making it uninhabitable, despite its location in the habitable zone.

Henrik Eklund, a researcher at the European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC), points out that the findings open up a new frontier for studying space weather on distant stars. As CMEs appear to be even more extreme around smaller stars, the study of these eruptions will be crucial for understanding how exoplanets retain their atmospheres over time and whether they can remain hospitable to life.

In the wake of this discovery, astronomers are now looking ahead to future missions that will help expand our understanding of stellar activity. The upcoming Square Kilometer Array, which will be operational in the 2030s, is expected to detect even more CMEs from distant stars, providing valuable data for the ongoing search for life beyond Earth.