Catherine Barnard and Fiona Costello examine Nigel Farage’s proposal to scrap welfare benefit access for EU nationals living in the UK. They explain the rights of EU citizens under the EU Settlement Scheme and the numbers currently accessing benefits, as well as the potential consequences of this policy that would breach the Withdrawal Agreement.

What goes around comes around. This time it’s Reform’s announcement that it would scrap welfare benefit access for EU citizens living in the UK under the EU Settlement Scheme (EUSS) should they form a government after the next general election. Is this possible? And if so, how?

Rights of EU citizens living in the UK pre-Brexit have been guaranteed under the EUSS set up under The Withdrawal Agreement (WA), an international Treaty negotiated and signed by both the UK and EU. Part Two of the WA preserves the rights that EU citizens had prior to Brexit, including access to benefits, such as Universal Credit (UC). EUSS introduced two statuses: (1) settled status (SS) (equivalent to indefinite leave to remain (ILR)) for those who had already lived in the UK for five years pre-Brexit; and (2) pre settled status (PSS) for those who have lived in the UK less than five years. Those in this second group need to make another application after five years to ‘upgrade’ to settled status (or may be automatically upgraded).

SS gives its holders an automatic right to reside for the purposes of accessing welfare benefits, including UC. This group needs only to prove they are ‘habitually resident’ in the UK. PSS holders, however, must prove their entitlement to access welfare benefits with additional requirements such as being in work.

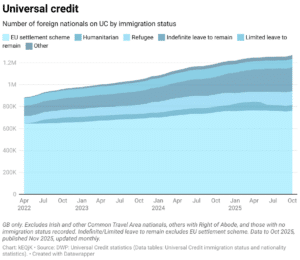

As the figures produced by Fraser Nelson show (see fig 1), those on EUSS are claiming UC in large numbers (see fig 1).

Fig 1 Foreign nationals claiming UC

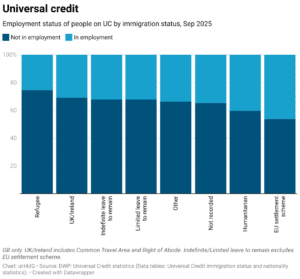

In fact, those with status under the EUSS are the foreign national group most likely to be both in work and claiming UC (see fig 2). This suggests – and our research supports this – that many EU citizens are in low paid work in the UK and are using UC to top up their pay. The pandemic showed us that many of the industries where these EU nationals work are essential– for example care workers or those working on farms and in factories. If this group were unable to ‘top-up’ their low paid work with UC, it is unlikely they would be able to remain in these jobs long-term. These jobs are shunned by British workers, but they do ensure cheap food, albeit subsidised by the taxpayer.

Fig 2 Employment status of foreign nationals claiming UC

If Reform were to unilaterally terminate the right to benefits for those under the EUSS, this would be a breach of the WA. The EU would undoubtedly start proceedings under the dispute settlement mechanism of the WA. This means, first, attempts to resolve disputes via the Joint Committee (Article 169), the body responsible for overseeing the implementation of the Withdrawal Agreement, failing which arbitration (Article 170).

If the arbitration panel finds against the UK and the UK refuses to comply within a reasonable time the EU could ask the arbitration panel to impose temporary remedies for non-compliance (Article 178) which include, in the first instance, a lump sum or penalty payment. If the UK then fails to pay or persists in non-compliance, Art 178(2) says the EU may suspend some of its obligations both under the WA (apart from citizen rights obligations) or now, more likely, ‘any other agreement’. This bridging provision links the WA to other agreements such as the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), the preferential agreement under which the UK currently trades with the EU. This means that the EU could impose tariffs on the UK. Nigel Farage has said ‘we can retaliate with tariffs. Two can play that game’. However, the EU is good at imposing tariffs, hitting states where it hurts. The EU may even decide simply to terminate the TCA because the UK is acting in bad faith and not complying with the rule of law by deliberately breaching a fundamental aspect of the WA.

Rather than try to navigate any dispute resolution of the WA, Nigel Farage has said that his party would look to renegotiate the Withdrawal Agreement. Discussion could be held in the Specialised Committee on Citizens’ Rights, established by the WA, which monitors the implementation and application of citizens’ rights. The Committee does not have the power to make such a major change to the Treaty. The Joint Committee did have powers to adopt decisions amending the WA ‘to correct errors, to address omissions or other deficiencies, or to address situations unforeseen when this Agreement was signed’, provided ‘that such decisions may not amend the essential elements of this Agreement’. Changes of the sort advocated by Reform would amend ‘essential elements’ of the Agreement; and the powers to amend have now expired anyway.

Assuming it is even possible to negotiate such changes, how would Reform get the EU back to the table? The EU will be reluctant to limit any of the rights it has already protected for its citizens in the UK, especially when some member states have already raised concerns that their citizens are not being treated fairly. Reform must also consider that any reduction in rights will work both ways, if welfare benefits are refused to EU citizens in the UK, they would also be refused to UK citizens in the EU. We know this number to be approximately 1.2 million people. Many UK citizens in the EU are older/retired people (approximately 460,00 are over 65), who may well not be in work and be accessing (or need to access in the future) social assistance in their EU home.

Considering the difficulty of renegotiating an international Treaty or the implications of reneging on international agreements, a more efficient way to address the numbers of those claiming benefits under the EUSS is to look at low paid or atypical work contracts and ask if more can be done to reduce reliance on welfare benefits as a means of subsidising low wages.

By Catherine Barnard, Senior Fellow, UK in a Changing Europe & Professor of EU Law and Employment Law, University of Cambridge and Fiona Costello, Assistant Professor, University of Birmingham.