A wolf in British Columbia was filmed fishing on April 29, 2024, pulling in a crab pot from the water and eating the bait. Video: Heiltsuk Wolf and Biodiversity Project.

A wolf in British Columbia was filmed fishing on April 29, 2024, pulling in a crab pot from the water and eating the bait. Video: Heiltsuk Wolf and Biodiversity Project.

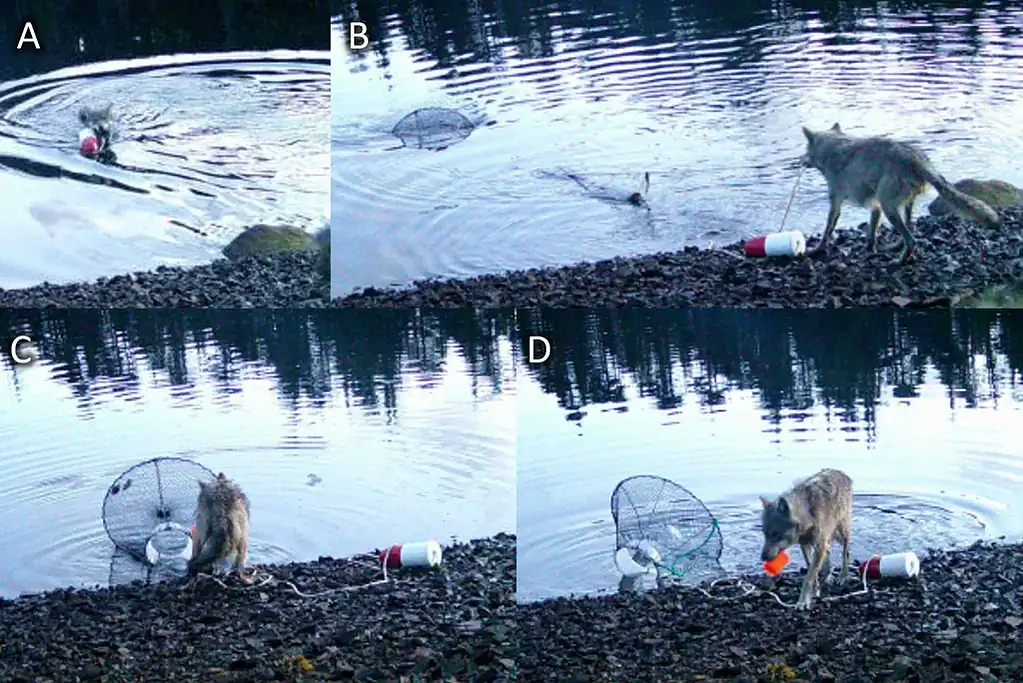

On the remote shores of British Columbia, a wolf waded into cold saltwater and seized a buoy in her jaws. With slow, deliberate movements, she pulled a crab trap line hand over paw — well, paw over rope — until the hidden cage rose from the depths. She tore through the mesh, extracted the bait cup, and ate the sea lion meat inside.

What looked like a three-minute heist was actually something stranger. And far more consequential.

Scientists say the brief scene, recorded by a remote camera in May 2024, could be the first documented instance of tool use by a wild wolf.

“We were not expecting that,” said ecologist Kyle Artelle of the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry.

The Mystery of the Mangled Traps

A wolf was observed pulling a buoy attached to a crab trap to the shore to eat the bait from the trap in Heiltsuk territory of the central coast of British Columbia. Credit: K.A. Partelle and P.C. Paquet, Ecology and Evolution, 2025

Artelle and colleagues with the Haíɫzaqv Nation — an Indigenous stewardship program that works to monitor and protect their territory — had been trying to solve a mystery: who (or what) kept destroying their crab traps?

The Haíɫzaqv (pronounced Heiltsuk) Nation has spent years combating an invasion of European green crabs, a species that threatens native clams, salmon, and eelgrass. Their Guardians began setting traps baited with herring and sea lion meat.

Then the traps began coming back in pieces.

Some were shredded or dragged ashore. Others, anchored in deep water, were never visible at low tide.

“We were really puzzled,” Dúqva̓ísla William Housty, director of the Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department, told Science Magazine.

At first, everyone blamed otters or seals. But the evidence didn’t add up. The mystery deepened until Guardian Richard Cody Reid and University of Alberta student Milène Wiebe placed a trail camera above the site in May 2024.

Within a day, the thief appeared.

The footage showed a female wolf swimming through the shallows, tugging the buoy in her mouth, then pulling the attached line in precise, repeated motions. When the submerged trap was within reach, she ripped through the netting, carried the orange bait cup to dry ground, licked it clean, and trotted off.

“This wasn’t just random tinkering,” Artelle told The New York Times. The wolf’s sequence, he said, was “unwaveringly purposeful.”

In February 2025, another camera caught a second wolf tugging on a partially submerged line. Two nearby traps were later found on shore with their bait boxes missing.

“The weight of evidence,” said Artelle, “suggests the female wolf or her full pack are responsible for the pilfering.”

Members of the Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk) Nation caught the crafty female wolf on camera. Credit: Artelle et al. / Ecology and Evolution, 2025

Members of the Haíɫzaqv (Heiltsuk) Nation caught the crafty female wolf on camera. Credit: Artelle et al. / Ecology and Evolution, 2025

Whether the wolf “used a tool” depends on how we define it.

Tool use, by one common definition, means employing an external object to achieve a goal intentionally. By that logic, the wolf qualifies. She recognized that pulling the rope would bring up food she couldn’t see.

But others argue a tool must be modified or reoriented, as when crows craft hooks or chimpanzees strip leaves from sticks.

“If this had been a chimpanzee or other nonhuman primate, I’m sure no one would have blinked about whether this was tool use,” said Marc Bekoff, a University of Colorado biologist.

The Ecology and Evolution study notes that the wolf’s actions “demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of the multi-step connection between the floating buoy and the bait within the out-of-sight trap.” Whether it reflects causal insight or brilliant trial-and-error, the authors write, it is still “noteworthy” behavior.

“Even if we don’t want to call it tool use,” Artelle told The New York Times, “the fact that the trap was completely underwater and out of sight makes it hard to argue that she didn’t understand the connection between all these steps.”

A Place Where Wolves Get to Be Wolves

Wolves along the Haíɫzaqv coast live differently from most. The wolves swim between islands. They hunt intertidal prey. And they are not hunted themselves.

That last part might be key.

“This is a place where wolves get to be wolves,” Artelle said.

In most of North America, wolves face persecution from hunting, trapping, or culling. In contrast, the Haíɫzaqv Nation’s relationship with wolves is one of kinship and respect. Their oral histories speak of a time when humans and wolves could shape-shift between forms.

“We’ve always maintained a very respectful relationship with the wolves up here in the territory,” Housty told the Washington Post.

Freed from fear, wolves here may have the time and safety to experiment. As the study’s authors suggest, reduced persecution could allow them to “develop confidence and devote time to exploring novel behaviors.”

That might explain how a wolf became curious enough to test a buoy, then smart enough to work the whole system.

The Broader Story of Animal Tool Use

The wolf’s cleverness now joins a growing catalog of animal innovation: octopuses carrying coconut shells for armor, elephants using branches to swat flies, pandas scratching themselves with bamboo, and dingoes shifting tables to reach food.

“Behaviors like this challenge us to rethink the mental lives of animals and how we treat them,” said Bradley Smith, a comparative psychologist at Central Queensland University.

The wolf’s behavior forces us to reconsider what intelligence looks like in the natural world. It isn’t limited to toolmaking apes or problem-solving crows. It’s also found in a wolf that can map the unseen geometry of rope, buoy, and bait — and act on it.