In November 2016, just months after the referendum, Boris Johnson stood at the Spectator’s Parliamentarian of the Year awards and declared: “Brexit means Brexit and we are going to make a Titanic success of it.” At the time it sounded like the usual Johnson bravado: reckless, jokey, weightless. Nearly a decade later, the phrase reads less like a joke and more like a verdict.

A major new study from the National Bureau of Economic Research has now provided the clearest picture yet of Brexit’s economic impact. Drawing on almost ten years of data, it shows that leaving the EU has not only damaged the UK economy, it has quietly, steadily, and comprehensively knocked it off course. Far from a momentary shock, Brexit has produced a slow-growth decade that no amount of political spin can disguise.

For years, arguments about Brexit felt abstract, mired in claims and counterclaims. But this new research removes the guesswork. It offers something Britain has lacked since 2016: a full, sober account of the consequences. And those consequences are stark.

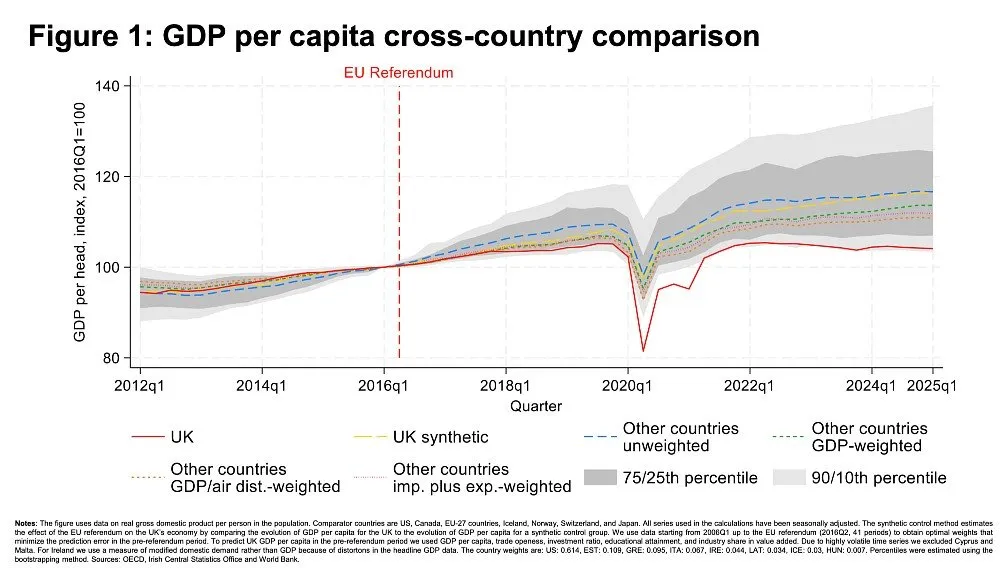

A self-inflicted lost decade Chart by National Bureau of Economic Research

Chart by National Bureau of Economic Research

The headline finding is devastating in its simplicity. By 2025, the UK economy is 6%–8% smaller than it would have been had we stayed in the EU. In economic terms, that is not a blip, a rounding error, or the unavoidable cost of “taking back control”. It is the loss of an entire decade of growth.

To put that in human terms: imagine wiping out the economic output of Scotland. That is roughly the scale of what has vanished.

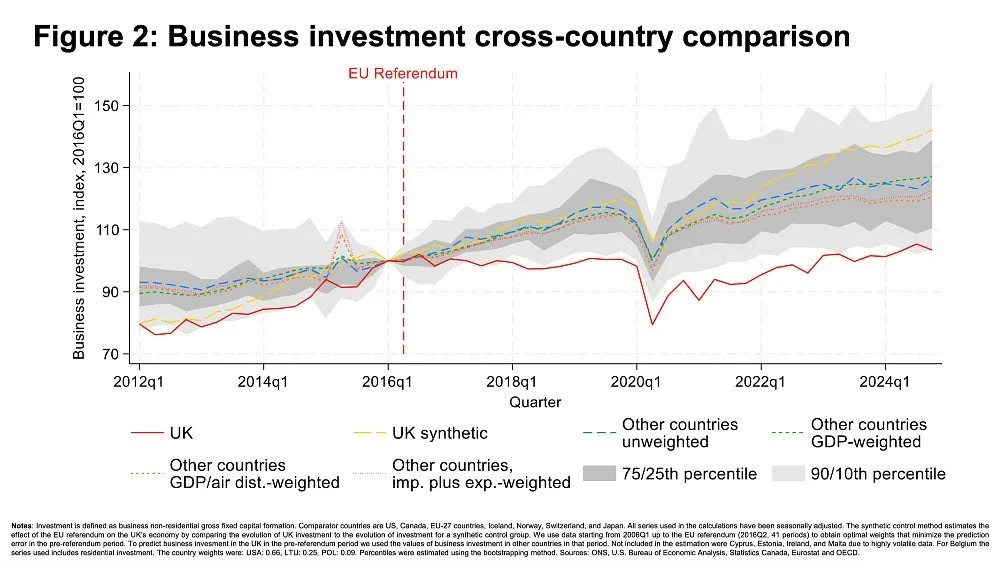

The picture becomes even bleaker when you examine what underpins that headline figure. Business investment is down 12%–18%. It means fewer factories were built, fewer laboratories opened, less new equipment purchased and less innovation. In the jargon of economists: we stopped building the future.

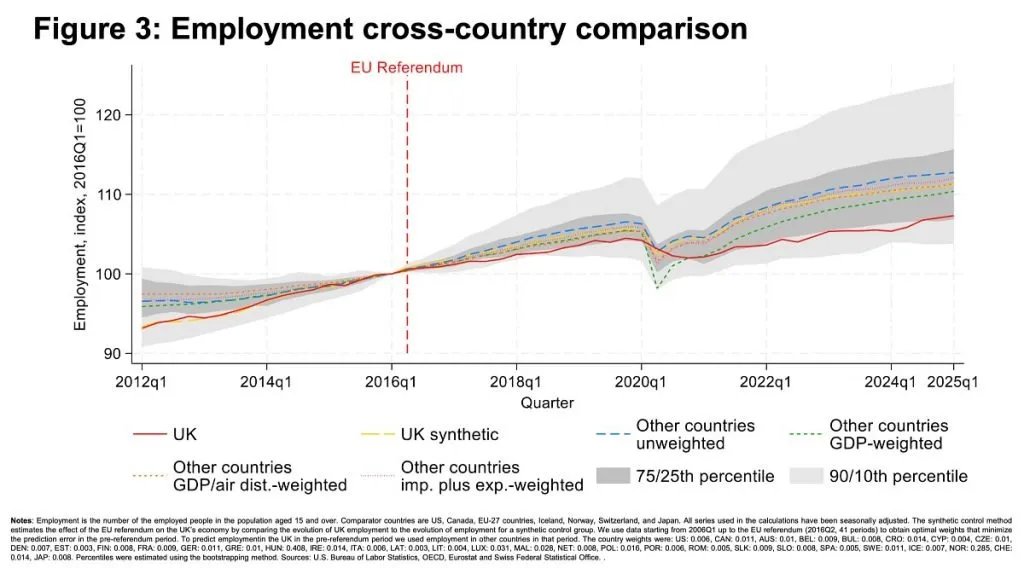

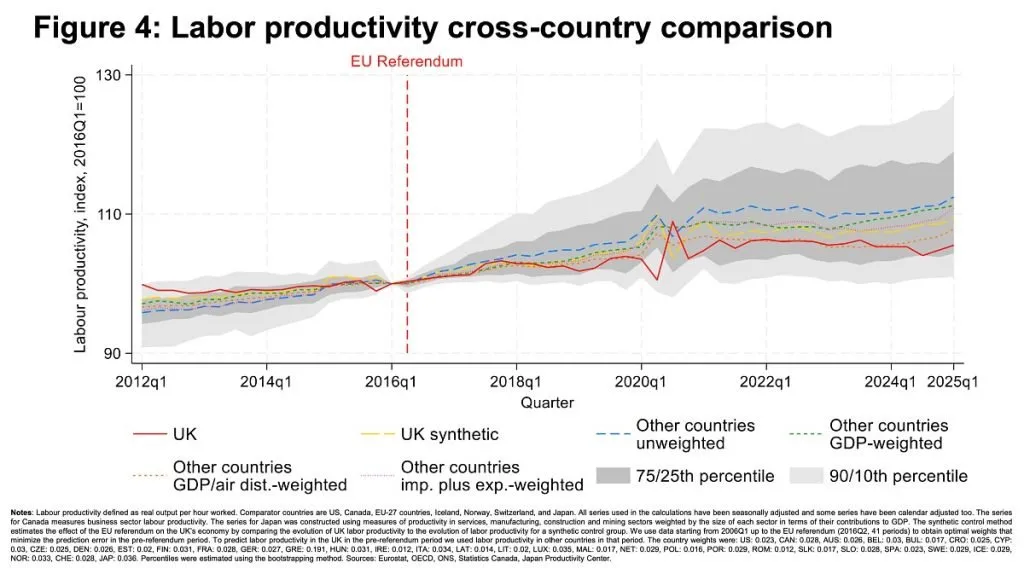

Employment is down 3%–4%: hundreds of thousands of jobs have never existed, never provided incomes, never supported families or local economies. Productivity – the long-term engine of rising living standards, and the key ingredient Britain desperately needed to fund decent public services – is down 3%–4% too.

If Brexit had delivered even one of the transformative benefits promised by its architects, those numbers might have been offset. But it didn’t. And the losses kept compounding year after year.

The economists dismissed as ‘Project Fear’ were, if anything, too cautious. Their forecasts predicted a long-term hit of around 4%. This new research shows the real damage is closer to 6%–8%, because the grinding uncertainty of the Brexit process magnified the harm far beyond what its architects were willing to admit.

The damage wasn’t one big hit – it was ten years of slow bleeding Chart by National Bureau of Economic Research

Chart by National Bureau of Economic Research

One of the most striking insights from the paper is that Brexit didn’t behave like a normal economic shock. There was no singular collapse or dramatic turning point. Instead, it created a rolling fog of uncertainty that lasted almost a decade.

Between 2016 and the present, firms were repeatedly forced to prepare for multiple possible futures: no deal, partial deal, Northern Ireland complications, changes to migration rules, shifting regulatory arrangements, and the long delay before anyone knew what trading terms would apply. That uncertainty didn’t just make life difficult for ministers. It made it impossible for thousands of firms to plan.

Senior managers spent hours every week firefighting Brexit-related logistics instead of running their businesses. Many firms stockpiled like it was wartime. Investment in research, development, training and technology fell. Migrant workers left, particularly in sectors that depended on EU labour. Innovation slowed as firms diverted time and money to navigating bureaucracy rather than improving productivity.

These aren’t abstract concepts, they are the lived experience of businesses across the country. They are the reasons why the UK was already falling behind comparable economies long before the pandemic or the energy crisis hit.

The international comparison is brutal

Charts by National Bureau of Economic Research

Charts by National Bureau of Economic Research

One of the strengths of the NBER study is that it compares UK performance with that of 33 similar countries. The conclusion is unavoidable: other nations grew steadily; Britain lagged behind.

GDP growth since 2016 has been markedly weaker in the UK than in almost every comparator country. That gap cannot be explained by Covid, because the UK’s Covid-affected years look broadly similar to others once you adjust for population. It cannot be explained by global shocks, because those shocks affected everyone. It is, overwhelmingly, the Brexit effect.

The authors even ran multiple versions of the comparison using different weighting systems to avoid bias. The outcome barely changed. No matter how you measure it, the UK is doing worse because it left the EU.

In other words: this isn’t the world doing badly and Britain being caught in the tide. This is Britain drifting backwards while others move forward.

For nearly a decade, millions of people who opposed Brexit were told they were exaggerating, scaremongering or refusing to ‘believe in Britain’. Yet the numbers now tell a different story.

Those who warned about the economic fallout were right. The experts were right. The people who marched, campaigned, wrote, protested and pleaded for honesty were right. The tragedy is that being right offers no comfort at all when the consequences are now baked into everyday life.

Why Labour’s problem is structural, not managerial

This slow-moving wreck has now landed squarely on the desks of Rachel Reeves and Keir Starmer. The government’s recent admission that there is a “hole” in the public finances caused by Brexit is not a political embarrassment, it is a mathematical inevitability. A smaller economy produces fewer tax receipts. Fewer tax receipts mean less money for public services, less for investment, less for wages, and less room to manoeuvre.

Improving the Trade and Cooperation Agreement would help at the margins, but the scale of the economic loss revealed in this paper shows how limited those gains will be. Even a significantly better deal with the EU cannot suddenly restore a decade of missed investment, lost growth, and weakened productivity.

It is, as one might put it, rearranging the deckchairs.

And Britain is not merely listing. According to this paper, we are already several metres below the waterline.

What happens now?

The country is still living inside the economic aftermath, whether Westminster wants to admit it or not.

There is a temptation among politicians to avoid dwelling on Brexit – to treat it as a closed question, something better left in the past. But as this research makes clear, Brexit isn’t in the past. It is present in every overstretched council budget, every cancelled infrastructure project, every school without enough teachers, every struggling business wondering how to cope with higher costs and lower demand.

For nearly a decade, the country has been told that Brexit was a matter of political will or national identity. This study reminds us that, ultimately, it is a matter of arithmetic. You cannot vote away the laws of economics.

Johnson wanted to make “a Titanic success” of Brexit. In one respect, he succeeded: we hit the iceberg. What comes next depends on whether we have the courage – or simply the honesty – to acknowledge the damage and start steering towards reality.

If Britain wants to recover, the first step is to stop pretending everything is fine. The second is to recognise that reconnecting with Europe may not be a political choice anymore, but an economic necessity.

This article is based on a paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research: “The Economic Impact of Brexit” by Nicholas Bloom, Philip Bunn, Paul Mizen, Pawel Smietanka and Gregory Thwaites, and written as a collaboration between ChatGPT and an East Anglia Bylines editor.

More from East Anglia Bylines Download the Bylines app to get our content straight to your phone!

Download the Bylines app to get our content straight to your phone!