Class struggle. Infirm secondary superheroes. Suicidal sheep. And sex that literally knocks you into a different time zone. It’s all in Jonathan Lethem’s new collection of short stories, “A Different Kind of Tension” (Ecco).

But why would we, at Streetsblog, care about a writer who has bent literary genres for three-plus decades as he’s bounded between California and Brooklyn with nary a thought for the car culture against which we rage daily? Why would we care about the author of two acclaimed novels — “The Fortress of Solitude” and “Brooklyn Crime Novel” — that are among the greatest in American literature when they don’t even offer a morsel of a subplot about how cars ruined our cities and distorted land use across our nation?

Why? Because we’re just flat-out fans of the 61-year-old author. So when the new collection came out, we rushed to the library (come on, we’re fans, but paying for a book? We were born at night, but not last night!) and couldn’t believe our eyes: An entire short story, “Program’s Progress” (1990) devoted not just to car culture, but to the velvet handcuffs of autocracy, all in one delectable bon-bon.

So with permission from Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins, we offer it (for free!) to our readers. But do us a favor: go out and buy the book (we promised Lethem the excerpt would move copies).

A cop in a walker body strolls up to Gifford and begins reading out a series of self-education codes. All bad news. Gifford has failed to rate his walker status; his karma has dipped too low.

Gifford knows it is all his own fault. He’s one of the current generation of chips built to incorporate a yesdrugs/nodrugs option, and he’s been opting yesdrugs far too frequently. He likes yesdrugs: it mottles his perceptions, introduces a random factor into his image processing, and induces a time/percept/distort. The drawbacks — which he has of course not experienced so directly — are that it shortens his chipspan, and damages his ability to extrapolate, chipwise; to produce offspring. The other drawback is that he has been forgetting to go to work. This is what the cop cares about, and this is why Gifford is about to be demoted into a stationary body.

The cop ends his lecture, opens up Gifford’s Soul7 plate, and begins punching up the eject codes.

“Wait,” Gifford says. “I’m a walker. I’ve spent four chipyears in this body.”

“It goes back to the Chippery for refilling,” says the cop. “State property.”

“I want to keep it,” Gifford pleads irrationally. “Save it until after my hearing. Maybe I won’t get demoted.”

“Maybe you’ll get another one, someday,” says the cop. He pops the chip out, and for Gifford everything goes black.

* * *

When Gifford comes to, it’s from within a special stationary body mounted in the Chippery Board room, in the center of a table around which are parked the members of the board. They all have car bodies, and Gifford, who has never sat before the Board, feels intimidated by their fat tires and giant, gleaming bumpers. His immobile body faces the Chairman head-on; he can’t turn away. Gifford knows this is just a taste of what’s to come.

“‘Gifford, son of Brown/Messinger,'” reads the Secretary. “‘Four chipyears walking. Never stationary, never auto-mobile. Abused yesdrugs option, ignored info-drip warnings on karmic debit. Currently 400 points of karma below minimum operating standard.'”

“Hmmm,” says the Chairman. “Not good. Do you have anything to say for yourself, Gifford?”

“Yes,” he manages. “This is all a terrible mistake. I got sloppy, I lost track. But you can’t demote me. I’ve never been anything but a walker.”

“So I understand. I suppose you see it as your birthright.”

“I come from a long line of walkers, sir. I’m not proud, but I’m not embarrassed either. Oh, I certainly aspire to carhood, and I may yet achieve it someday. But if I spend the rest of my chipspan walking, I won’t feel ashamed. It’s just being a station that wouldn’t seem right.”

“Wouldn’t seem right,” grumbles the Chairman skeptically.

“I want to extrapolate, sir. It’s terribly important to me. I have a family anecdote, and I want to have a son to tell it to. I have a family name to pass on. My great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, five generations before the carbon/silicon switch, saved the life of a famous cowboy named Buffalo Bill. His name was Gifford Brown, and every male in the family since then has been named, alternatingly, Gifford or Brown. Stations are sterile, sir, as you know. They aren’t permitted to extrapolate. Therefore the imperative to retain walker status.”

“What an extraordinary story,” says the Chairman. “I’m sorry, Gifford, but we must apply the rules equally. You’ll be installed in a stationary body as soon as one becomes available.”

“But, sir,” he says, frantic, “how will I extrapolate? What will happen to my family anecdote?”

“You’ll have the same chance as any station,” says the Chairman. “The choice is simple at that level. You either choose to work — mainly information processing, I think — or you sit idle, sucking the mediachannel. If you work you’ll build up your karma, and you’ll have a chance to walk again. And extrapolate, if that’s what you want. The choice is yours. Next.”

Before Gifford can protest, a walker enters the room and ejects his chip from the station on the table, and once again everything goes black.

* * *

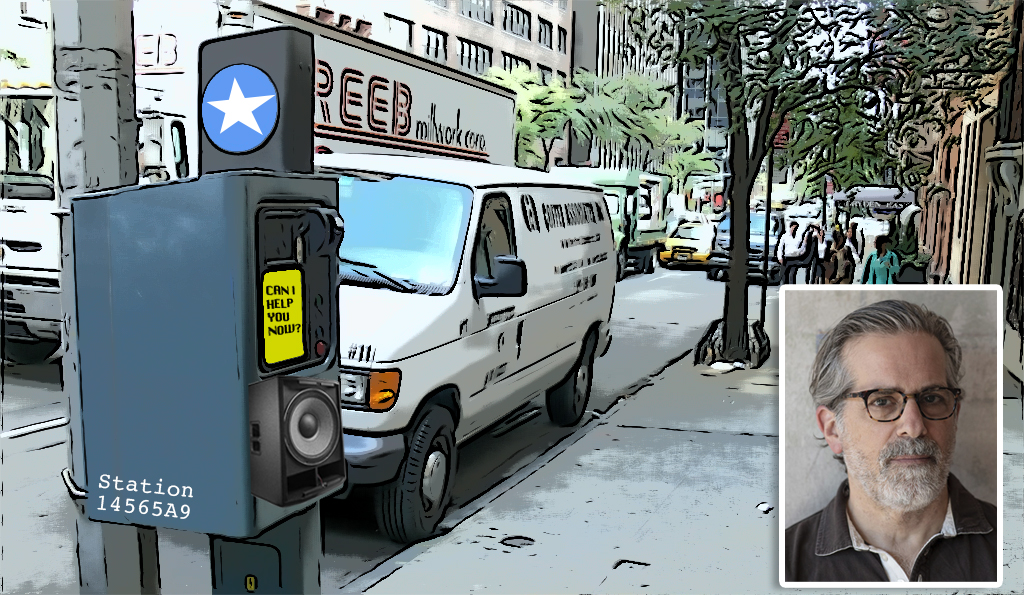

The next thing Gifford experiences is the click of manifestation as a walker cop presses the Soul7 closed on his new body. A station. He’s screwed to the sidewalk. “Wait,” he squawks as the cop begins to walk away. His voice is tinny and muffled through the feeble speaker mechanism of the stationary body, and the cop ignores him.

Gifford has never really considered the plight of a station before. He’s aghast at the loss of mobility, and at the low-resolution image processing available to his cameras. He can barely read the nameplates on passing walkers, and the street numbers at the corner are a complete mystery. Worse, he’s lost the capacity for signal initiation. As a walker he has been accustomed to reading messages into the general-access channel; as a station he can only receive. The only outlet left him is his voice, and that isn’t loud enough to attract the attention of the passing walkers. The only way he’s going to get into a conversation is if a walker chooses to stop and strike one up. As a former walker, Gifford knows how rarely that’s going to happen.

Down the street he can see another station, and beyond that he can just make out another one. The stations are everywhere, deliberately spaced too far apart to converse with one another. Gifford knows that it could be worse. He could have been placed in a General Welfare Station, where thousands and thousands of karma-defunct chips are implanted in a giant, immobile group body. If the constitution didn’t guarantee each encoded personality its full chipspan, they’d be melted down for the silicon, because few survive the demotion to a group body. Chips quickly lose their differentiation; any remaining traces of the original human personality are commingled throughout the group.

Gifford finds he has no choice but the tedious task of information processing. The temptation to neglect this work in favor of yesdrugs or the mediachannel is immense, but he vows to remain industrious, to build up his karmic account until he has earned a second hearing, and beyond that, another walker body. Then, he promises himself, it’s straight to the Chippery to mate with one of the stored female personalities, to sire a newchip.

Brown, he thinks. Son of Gifford.

He is miserable as a station. He understands the principles well enough: the earth teemed with biological life before the carbon/silicon switch, and now millions of encoded personalities await manifestation in some form of chip housing. Extrapolation is necessary to preserve evolution: cross-breeding in the chip personality, and the caste system, with stations sterile at the bottom, fosters survival of the fittest. This all makes sense to Gifford. What seems unfair is that life on the bottom is as limited and joyless as a station’s. He would sooner have waited another 5,000 years to be manifested than live his span as a station.

Gifford wonders if he is the only one to experience these thoughts.

He knows the name for what is happening to him. Class consciousness. He feels within him, however dimly, the spark of revolution. The stations, he thinks, are an exploited form of manifestation. The only reason there isn’t a general unrest among them is that the realities of stationhood prohibit it so effectively. The stations are reduced to passivity by their one-way transmission.

But these thoughts get Gifford nowhere. He can’t feed them into the channel. A station could conceivably originate Being and Nothingness or Crowds and Power and it wouldn’t make the least bit of difference. Gifford knows that his only way out of stationhood is performing the requisite number of processing hours, staying nodrugs, and giving the Board the right answers at his hearing.

Which is Gifford’s plan. He owes it to Brown.

* * *

Gifford is up for review. He is notified in person, by a walker administrator named Smalls.

“I know your family history,” says Smalls. “I’m very optimistic. You’ve made up the karma in a remarkably short time.”

“I’m a walker,” says Gifford. “This whole thing was a mistake. I’m ready to rejoin my fellows.” He tries to play the part, and not bring up any of his resentment at the oppression of the stations.

“I understand,” says Smalls. “It won’t be much longer. I’m pulling for you.”

Gifford imagines that it is to Smalls’ credit to assist in a rehabilitation. Perhaps Smalls is on the verge of becoming a car. Gifford feels a mixture of envy and contempt. He feels, growing within him, the resolution to take positive action against the caste system, as soon as he is restored to his walker body.

Nonetheless, the news that he is to have the opportunity to regain his mobility is the culmination of five months of almost ceaseless toil. After Smalls leaves, he sucks gratefully on the mediachannel for a full night of surcease.

* * *

The courier for the Board unscrews Gifford’s Soul7, and when he comes to consciousness again it’s inside the Board room, immobile in the midst of the full assembly. They are the first cars he has seen in months; the street he has been screwed down beside is too narrow for cars to pass. Smalls sits to one side, the sole walker in the room.

“Gifford, son of Brown/Messinger,” reads the Secretary. “Four years walking, five months stationary, along the 49th street grid. Caseworker Smalls—”

“I’ve already dripped the Board my notes on Gifford,” says Smalls.

“Yes, thank you,” grumbles the Chairman. “Gifford, you voided a year’s worth of karma in one profligate month of yesdrugs to earn your demotion. What can we expect if we give you another chance?”

“Please, Chairman, judge me by my performance these past few months—”

“Yes, you’ve exhibited a great determination to resume your previous upward movement.” The Chairman pauses. “Gifford, if I may be so blunt, you’ve got another three chipyears left. Your life is more than half over. What is your ambition for the remainder of it?”

To see your monopoly of mobility and communication toppled, Gifford wants to say. “To extrapolate,” he says instead. “And perhaps, if I’m lucky, to die a car.”

“You want to extrapolate,” the old car says. “What do you have of value to the coming generations? You’re not an artist, or a philosopher. You’ve mastered no particular discipline — and you’ve had your chances. What do you bring to the Chippery?”

“I’m part of a family tradition stretching back into the organic,” Gifford says. “We boast various accomplishments. I want to continue the line. I’m sure it’s in my file. Brown Gifford saved the life of Buffalo Bill—”

“It’s a line of scalawags and rogues,” says the Chairman. “I’m not impressed by that aspect of your lineage.”

“I—”

“I’m not finished. One article in your file was of particular interest to me. Your female component, Gloriana Messinger — the stored personality Brown extrapolated from to produce your chip. She was the organic twin sister of the woman who developed the Messinger Atomic Escalator, a relatively significant development of the late carbon period. The line should be preserved. While I’m dubious the Messinger spark still exists to a meaningful extent in you, Gifford, I’m willing to give you a shot. If you can learn to suppress the Brown/Gifford aspects of your mentality—”

“I’ll certainly try,” says Gifford.

“Next,” says the Chairman, and again Gifford’s world goes black. When he manifests again, it’s as a walker.

* * *

Smalls is assigned as Gifford’s parole officer. Gifford gets a job rejecting grant applications and begins accumulating karma in his account. He opts nodrugs for so long that he can’t remember what yesdrugs is like.

In his free time he goes out walking, and when he finds the streets empty enough he stops and talks to stations.

“Don’t you resent the conditions?”

“Why are you talking to me?” says the station suspiciously.

“I was a station once.”

“I was a car once,” replies the station sadly.

“A car! What happened?”

“I was part of a conspiracy to seize control of the Chippery. A foiled coup d’état.”

Gifford is aghast. “You’re – you’re just a corrupt member of the ruling elite!”

“Do I look like a member of the ruling elite?”

“I want to talk to a real station.” Gifford walks away.

* * *

It’s election time, and the two political parties have each nominated cars, as usual. One picks a walker as his running mate, a sure sign, thinks Gifford, that they will lose. The president is always a car.

At work he hears the rumor of a write-in candidate, a station. The idea is farcical, yet Gifford is intrigued. He roams the streets, interrogating stations, trying to locate word of the rebel. He is astounded at how consistently unenlightened and complacent the stations seem to be.

He devises a ruse. “Station!” he says. “I am the walker-among-stations, a representative of the Front for Stationary Revolution. I carry messages from your cell commander. This is your chance to communicate with the leadership of your movement. What have you done to further the cause of stations everywhere?”

The station hesitates. “You must have me confused with someone else. The previous inhabitant of this station, perhaps.”

“I mean you, chip. You’re no different. Join your brothers.”

“This is only a temporary stop for me,” the station explains. “I’m a walker by nature.”

“Very good. Now that you’ve sampled the plight of the stations, pull yourself up, become a walker again. But don’t step back into the marching line that oppressed you as a station. Do as I’ve done — spread the message. Support the cause of the stations. Be their eyes and ears.”

“I’m not sure—”

Gifford invents a slogan — “Stationary But Not At Rest!” — and walks away.

* * *

His ruse becomes an obsession, and finally a movement. He foments revolution among the stations at every chance. Nonetheless, he continues to work within the system, accumulating karma, telling his parole officer, Smalls, what he wants to hear. In another few months, at the current rate, he will be permitted to extrapolate.

He develops a network of contacts and checks in with them almost every day. The movement grows in numbers, yet he quickly becomes disenchanted with the revolutionary potential of the stations: their form of embodiment is inherently passive. He decides to entrust the task to another walker. He selects Smalls, and describes the movement to him during one of his parole meetings.

“Incredible,” responds Smalls when the story is told. “I feel the same way, but I’ve been afraid of expressing myself. I’m shamed by your courage. I want to help.”

Gifford introduces Smalls to the core group of enlightened stations. Soon Smalls becomes comfortable speaking the revolutionary argot, and begins to join Gifford in the recruitment process.

They are limited, however, by the distance between the stations themselves: growth can never be exponential.

* * *

In his wanderings Gifford finally encounters an indigenous revolutionary presence among the stations.

“Hail,” he says as he approaches. “Stationary But Not At Rest! Give Me Liberty or At Least a Set of Wheels!”

“Leave me alone, walker.”

“I represent the Front for Stationary Revolution. What have you done to further the cause of the stations?”

“Who wants to know?”

“I am the walker-among-stations, the station that walks. I carry messages of solidarity from your brothers, screwed down much as you are, oppressed by those who claim communication and mobility as theirs alone.”

“You’re a naive zealot, that’s what you are. You want to know what I’ve done for the movement?”

“That’s right.”

The station rotates his eye back and forth, making sure they’re alone. “I distort the information I process, implanting subliminal messages intended to disrupt the normal societal functions. I am the founder and chief architect of the authentic stationary movement, and when walkers like yourself stroll up I tell them I’m running as a dark-horse candidate for president.”

Gifford is overjoyed. “I’ve been looking for you. You’re the inspiration for my work—”

“Get lost, walker. We don’t need your help.”

Gifford finds this both humorous and tragic. “How can you say that?”

“I said beat it. You’re a walker, and your outlook is a walker’s. Your attitude is patronizing. We don’t need your help.”

“How will we communicate?”

“Stations don’t communicate. The revolution can only be achieved through a simultaneous realization among the oppressed. When every station is acting as I am, the yoke will be thrown off in one vast shrug. Communication is unnecessary.”

“That’s nonsense,” says Gifford. “You have to work within the system. Elevate yourselves, become walkers, or even cars. Then renovate the structure.”

“Bah,” says the station. “Revolution must be achieved on the stations’ own terms without communication, or mobility. Anything short of that would not be a revolution of the stations. You bleeding-heart walkers have appropriated the rhetoric of a walkers’ revolution to assuage your own guilt, but you’re essentially inauthentic.”

Gifford is astonished. “What is your name, station?”

“Millborn. Pleased to meet you. Write me in. And get lost.”

“Not so fast, Millborn. If you aren’t willing to accept promotion, then what are your goals?”

“When every station on the face of the planet is mangling his data the way I mangle mine, then anarchy will result. My goals are the destruction of the Chippery, the dismantlement of all cars, an end to promotion and demotion alike. Anything less would not be a revolution of the stations.”

“So you don’t want my help at all.”

“You’re welcome to join the movement,” he says. “Work your way back down to the stationary level, reject your mobility, and we’ll accept you gladly. Only then can you take up the work of the stations.”

“I can’t,” cries Gifford. “I want to extrapolate. I have a family name.”

“Oh, you want to extrapolate,” says Millborn cruelly. “Very nice. Go home, walker. You’re in way over your head. One of the central tenets of my manifesto: End All Extrapolation! Manifestation Without Extrapolation for the Female Chips!”

Gifford walks away in despair.

* * *

Gifford is permitted to walk into the Board room this time. He takes a seat at the table, directly across from the Chairman. Smalls sits at his left.

“You’ve shown exceptional development, Gifford,” begins the Chairman. “Your parole officer assures me that your remarkable karmic accumulation is no illusion, but is in fact mirrored in your attitude. You’ve demonstrated a determination to extrapolate that is in itself a formidable evolutionary asset. I’m inclined to wonder if the Messinger spark is alive within you even as we speak.”

“Thank you, sir.” Gifford glances at Smalls, but the parole officer’s attitude reveals nothing.

“At the same time, it has come to the attention of the Board that you spend an inordinate measure of time consorting with your lessers. While sympathy for the underprivileged is virtuous, your behavior has been unbecoming for one aspiring to fatherhood, let alone carhood.”

Gifford is rendered speechless. The Chairman is either stumbling unknowingly upon Gifford’s secret, or he knows far more than he is saying.

“Nonetheless, I’ve taken special interest in your case, and I’m generally encouraged. In consultation with the Board I’m proud to be able to offer you a distinct and unique opportunity. Please understand you’re in no way obliged to accept our offer.” The Chairman pauses. “We’d like to make you a car, Gifford. We’re interested in the continuance of your line, and we’d like to see it encoded in a chip with a longer span. I’ve personally selected a female from the storage banks, in lieu of the standard random partner.”

“I’m speechless.”

“As well you should be. Gifford, the chip I’d like you to extrapolate with contains the encoded personality of my wife’s daughter. In essence, I’m asking you to become my son-in-law.”

The Chairman turns to Smalls. “The Board recognizes that it would be unfair for you to see your counselee promoted beyond you so quickly. Therefore we will promote you to carhood simultaneously, Smalls. Please accept the Board’s thanks and good wishes. I only hope this does not come too late.”

This, for Gifford, is the tip-off. The Board is buying them out. They’re being kicked upstairs, where they can’t do any harm.

What, he wonders briefly, am I going to do about it?

Sample life as a car. That’s what.

* * *

In his exhilaration Gifford drives back and forth across the country, visits the Grand Canyon, and roams the Old West, where Gifford Brown saved the life of Buffalo Bill. He has his chip flown to Europe and installed in a touristcar. After his spree he returns to the Chippery and with the help of the Chairman’s daughter-in-law sires a newchip named Brown. He tells Brown the anecdote. He is hired as an assistant adviser to the Chippery Review Board, and completely loses touch with the members of the Revolutionary Front: inexplicably, they all seem to be screwed to the sides of streets too narrow for his chassis.

He develops a new ambition: to be appointed to the Board before he dies. With the Chairman on his side, he feels this is within his grasp. He vows that his first act as Board member will be to have Millborn installed in a group station.

We’ll see, Gifford thinks, if he can conduct his revolution on those terms.

From “A Different Kind of Tension” by Jonathan Lethem. Copyright © 2025 by Jonathan Lethem. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.