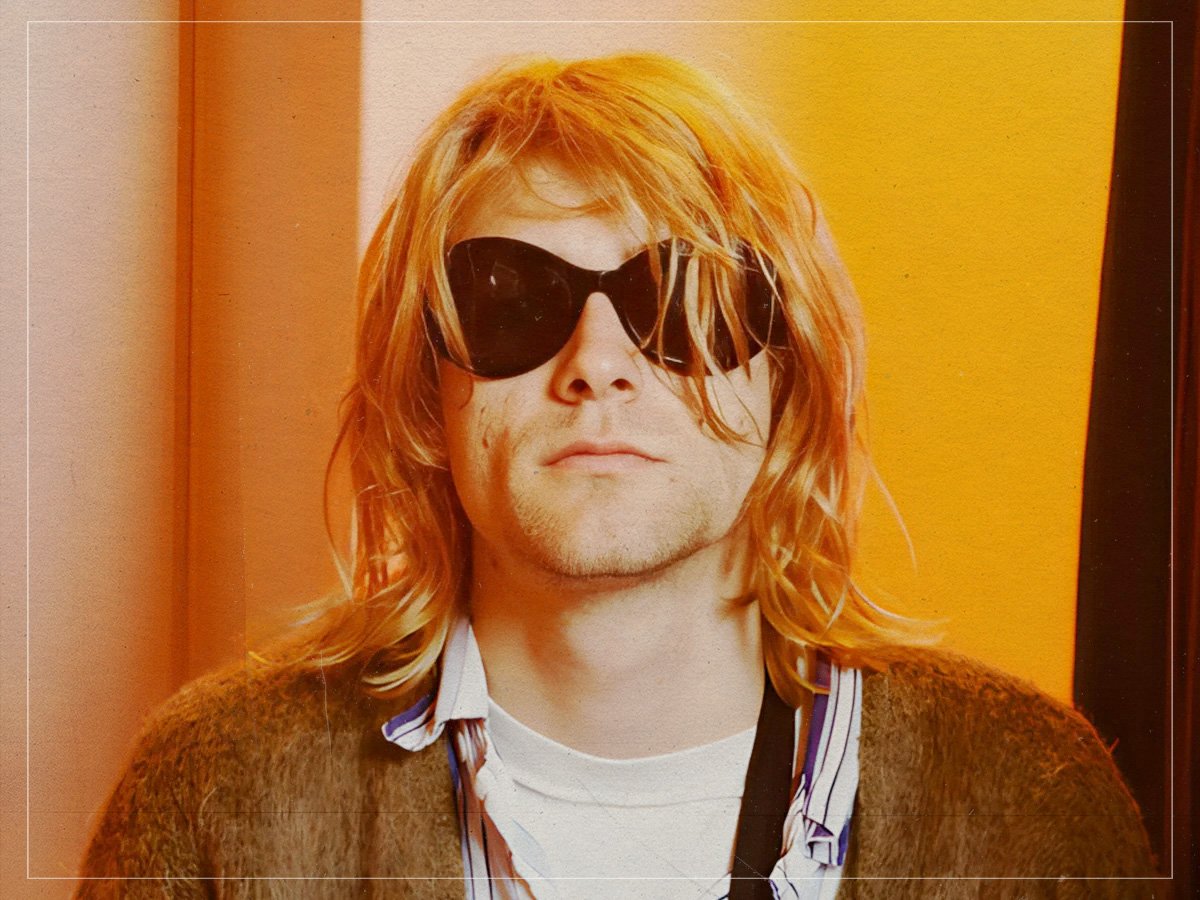

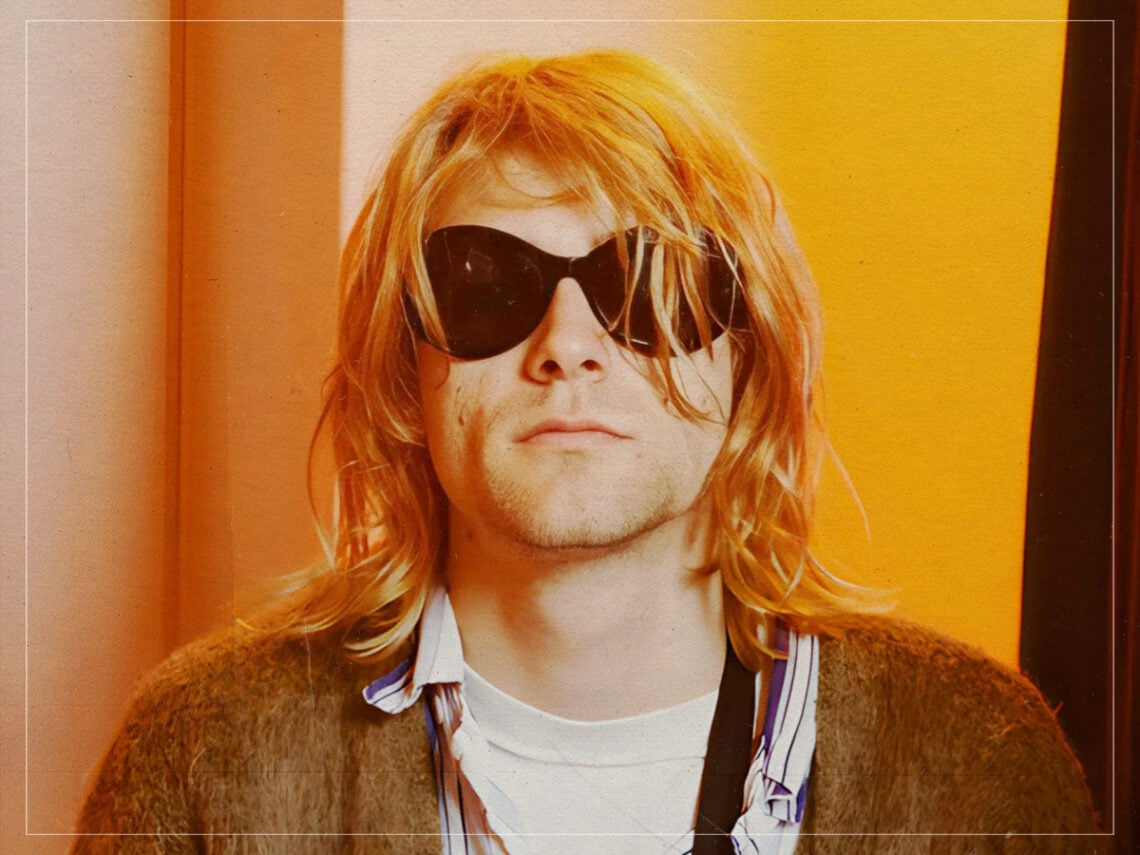

(Credits: Far Out / Nirvana)

Wed 26 November 2025 11:00, UK

No one in team Nirvana, least of all frontman Kurt Cobain, was expecting quite the dizzying success they’d achieve in late 1991.

Not that a comfortable chart presence wasn’t sought after. Shaped by punk and the jangly end of the left-of-the-dial college rock, Nirvana was happy to make a sonic leap away from the lo-fi murk of their debut, Bleach, toward a sophomore effort bigger, beefier, and more polished than the stripped-down sound popularised by producer Jack Endino amid the Seattle underground. Courted by the major labels, a signing with DGC after a spell with the indie Sub Pop Records would yield a larger budget and Butch Vig’s upgraded studio polish.

While the mainstream was being entertained, no one expected Nevermind to knock Michael Jackson off the Billboard 200 top spot. The trio didn’t pull this off by themselves. As is often erroneously regaled in rock lore, the bustling alternative was alive and kicking by the end of the 1980s, already chipping away at the spandex buffoonery mugging the day’s MTV during the fatigued end of hair metal’s pomp. But as the grunge dam was swelling to bursting point behind them, all it took was the final pop of ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’s opening riff to explode the flannel shirts all over the Hot 100 from then on.

Naturally, such catapulting to Top of the Pops and Rolling Stone front covers never sat entirely comfortably with Cobain, who always remained a punk kid at heart and never harboured serious aspirations toward Grammy nominations or VMA shows.

Despite sitting at the lofty top of the music biz, a healthy irreverence for the rockstar role, as well as his own self-deprecating minimising of his high-profile stature, fuelled a cynicism about musicians’ tendency to lean into spokesperson roles on the political issues of the day, making half an exception for one of West Coast hardcore’s titanic forces.

“They’re trying to make people aware, but I really can’t think of anyone who’s really schooled enough to be political to the point that would be required for a rock star,” Cobain told The Advocate in 1993. “If Jello Biafra was a big international star, it would be really cool. But he’s not on a major label, and he doesn’t write commercial enough music to use that as a tool.”

If one band were to define San Francisco’s punk scene, Dead Kennedys would reign supreme with little protest. Spiritually burnished in the city’s White Night riots, frontman Biafra proved the perfect force of nature for Dead Kennedys’ serrated surf rock attack, throwing himself into a live-wire absurdist theatre on stage and spitting satirical barbs at the rotten political class, be it Republican dinosaurs or democrat ghouls.

Such even-handed bile dished out across the political spectrum perhaps would have struck a more pertinent nerve in today’s climate, where the uniparty mulch that clogs up Congress on both wings is loathed more fiercely than ever.

But back in the early 1990s, Biafra’s Yippe anarchism and socialist orbiting activism looked far beyond the national mood and political possibilities of the day, much of the arts world enthused by Bill Clinton’s presidency after years of conservative administrations. Coupled with a continuing music career anchored to the underground, Biafra’s post-Kennedys output stayed put in the fraught waver of mainstream’s fringes, likely exactly where he liked it.

Funnily enough, Cobain expressed support for one of Biafra’s most famous lyrical targets. “I would have rather had Jerry Brown,” he stated when asked about his thoughts on Clinton’s presidency. The former Californian governor who challenged Clinton in the party primaries, Brown found himself at the centre of Dead Kennedys’ debut single ‘California Über Alles’ as the hippie-fascist dictator of a liberal totalitarianism in one of Biafra’s most venomously satirical visions.

Related Topics