Almost a decade on from the UK’s EU referendum, has Britain finally moved on from Brexit? Drawing on a new study, Anne-Marie Houde and Louis Stockwell show that while Brexit has receded from the spotlight, it continues to haunt the political imagination of voters.

“I don’t want another five years of the only thing we talk about being Brexit.” That comment, shared by a focus group participant in Oxford in 2024, captures a widely shared sentiment in post-Brexit Britain.

In a new study, we find that nearly a decade after the 2016 referendum, the EU has receded from the spotlight, yet it has not disappeared. In fact, Britain’s relationship with Europe remains an unresolved issue, prone to flare-ups in moments of crisis.

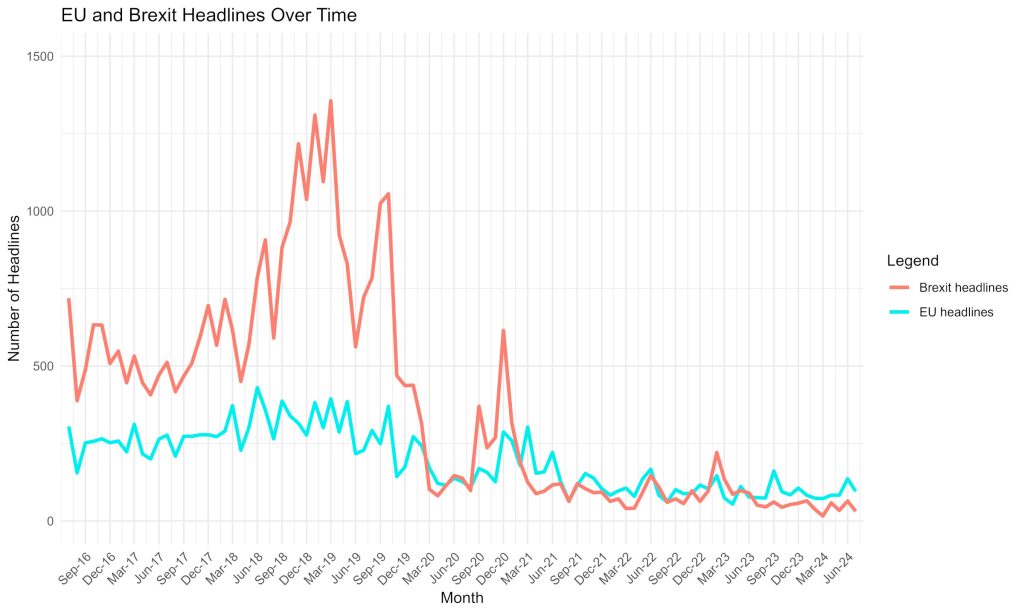

Drawing on new focus group data and a longitudinal media analysis of over 60,000 headlines from 2016 to 2024, we explore how public and media narratives about the EU have evolved.

We find that while the intense politicisation of the EU peaked between 2016 and 2019, it has since given way to a more subdued but emotionally charged state: one marked by disappointment, disconnection and a lingering sense that the EU is no longer central, but never quite peripheral either.

Brexit fatigue in the media

The media played a pivotal role in fuelling EU politicisation before and after the Brexit referendum. At its height, Brexit dominated the political news cycle. In 2016, British newspapers ran over a thousand EU-related headlines in a single month. By 2024, that number had dropped significantly. But the decline was not linear.

As Figure 1 shows, there were sharp spikes in coverage around critical junctures: the 2019 general election, the COVID-19 “vaccine wars” and the Northern Ireland Protocol disputes in 2021-22. During these episodes, emotionally charged and combative headlines returned, invoking “deadlocks”, “betrayals” and “Brexit chaos”. This suggests that while Brexit is no longer a daily media obsession, the issue remains latent and ready to resurface under the right conditions.

Figure 1: Indexed monthly coverage of the EU and Brexit in the British media post-Brexit

Note: Base = July 2016. For more information, see the authors’ new study in the Journal of Common Market Studies.

By summer 2024, however, coverage had become strikingly technocratic. Articles focused on trade fine-tuning, regulatory alignment or EU decisions unrelated to the UK. Notably, Brexit was almost absent from the 2024 general election campaign. As one headline put it: “Why is nobody talking about Brexit in the UK election?”

Citizens want to move on – but can’t

In our focus groups, participants across generations and political leanings described a sense of Brexit fatigue. Many, including Leave voters, felt let down by how Brexit had been handled. Some compared the UK’s departure from the EU to a divorce – irreversible and messy, but ultimately something the country now had to live with.

Yet this weariness was not the same as indifference. People felt the issue had been mishandled and felt emotionally drained due to overexposure. One student participant noted, “it just feels like everything’s gone worse since Brexit but it’s probably not because of that”.

Both Remain and Leave voters expressed regret, not necessarily about the outcome, but about how little they understood at the time. Misinformation and false promises came up repeatedly. Some participants felt they had been manipulated. As one older Brexit supporter said, “it was generally sold to us as being a rather straightforward and simple operation”.

These findings point to a distinct form of depoliticisation – not a loss of interest, but a loss of trust. Participants were not disengaged from the issue, but felt disempowered by it. They had, in many cases, stopped investing energy in Brexit because it felt futile. Some talked about wanting to move on not because they felt closure, but because they were tired of conflict.

Parallels could be drawn here to the fallout from other contentious referendums that were designed to “settle” decades of polarised debate. In particular, to the demobilisation of the Quebec sovereignty movement in an environment of constitutional “fatigue” following the 1995 referendum.

The emotional fatigue of Brexit took different forms, however. For some, it was a sense of national isolation. One participant observed that “we’re definitely more disconnected from Europe now”. For others, it was confusion about Brexit’s actual impact. Across groups, people struggled to separate Brexit’s effects from those of the pandemic, economic turmoil or broader political instability.

The EU as a “dormant issue”

Despite the fatigue, the EU has not disappeared from people’s minds. Many participants acknowledged that the UK would never be fully detached from Europe. “We’ll always have a relationship with the EU, whether we’re in or not,” said a participant from a lower socioeconomic status group. Still, few believed Brexit would be reversed. Even Remain supporters doubted the political appetite for rejoining. Instead, they imagined a more pragmatic, less antagonistic relationship.

The lasting effect of Brexit, it seems, is not an end to EU debate, but a shift in tone. The conversation has moved from a polarised standoff to a low-simmering question mark. The emotional charge has faded, but the issue remains unresolved and, for some, unresolvable.

Our research suggests that Britain’s EU debate is now governed by something approximating the inverse of what Edgar Grande and Hanspeter Kriesi call “punctuated politicisation”. In other words, a steady decline in the volume and intensity of public contestation over Europe as the issue becomes dormant beneath more pressing concerns, such as the cost-of-living crisis or NHS funding. Yet, in moments of stress or geopolitical conflict, it can re-emerge abruptly, reigniting familiar divides.

While these ebbs and flows of EU contestation have been observed across many member states, and are therefore not entirely unique, this inversion of the EU-wide trend of rising politicisation in recent decades does point to a distinctively new, semi-depoliticised, dynamic.

In the UK, the EU’s first major former member state, fatigue and institutional change may have driven the EU lower in the order of domestic political priorities. Yet the UK’s relationship with the EU remains a wound that can easily be reopened, as well as a key foreign policy preoccupation.

The findings from our focus groups suggest that this liminal status makes it harder, not easier, to achieve closure. In this sense, Brexit is not so much a chapter that has ended, but a thread that runs through the background of British politics.

The politics of unfinished business

Brexit may no longer dominate the headlines, but it continues to haunt the political imagination. The EU has become, in many ways, a symbol of unfinished business, not just in trade or regulation but in identity, belonging and Britain’s place in the world.

While our study highlights a clear decline in polarisation and salience, it also underscores the emotional aftershocks that politicisation leaves behind. Apathy, we found, is not the absence of interest in politics – it’s often the residue of overexposure, disillusionment and unmet expectations.

Whether the UK–EU relationship remains in the background or returns to centre stage will likely depend on future crises. But one thing seems clear: Brexit is not something Britons still want to fight over, but it’s also not something they can forget.

For more information, see the authors’ new study in the Journal of Common Market Studies.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of LSE European Politics or the London School of Economics.

Image credit: M. W. Hunt provided by Shutterstock.