- In Sri Lanka’s southern district of Hambantota, authorities have launched a large-scale elephant drive, mobilizing wildlife officers, armed forces and villagers to push herds from villages into what is known as the Managed Elephant Reserve (MER).

- Conservationists warn the Hambantota operation could mirror past failed drives, such as the 2006 drive in the south and the 2024 operation in north-central Sri Lanka that left elephant herds stranded.

- Experts urge a shift from elephant drives to implementing coexistence strategies, including habitat management and community-based fencing, as outlined in Sri Lanka’s national action plan to mitigate human-elephant conflict.

- Despite having reliable data on Asian elephant behavior and HEC, local scientists lament Sri Lanka is not adopting a scientific approach to find solutions to HEC while repeating past mistakes.

See All Key Ideas

COLOMBO — Playful 7-year-old Thinuli loved accompanying her father to his chena fields in a remote village in Hambantota, in Sri Lanka’s deep south. In August, she joined him as usual, eager to help in the field before the heat of the day. But in a tragic instant, an elephant charged out of the nearby thicket. Her father tried to save her, but it was too late. The elephant trampled Thinuli to death and left her father critically injured before retreating to the forest.

Two months later, in October, tragedy struck again, but differently. A pregnant female elephant was found shot dead in a nearby area, her body lying near a crop field she had likely entered in search of fodder. The fatal bullet, reportedly fired by a farmer defending his field, claimed not only her life but also that of her unborn calf.

These twin tragedies, occurring just kilometers apart, illustrate the worsening struggle between humans and elephants in Hambantota. Both humans and elephants are fighting for survival in a shrinking landscape, but only humans have a voice to demand solutions.

Under growing pressure to address the escalating human-elephant conflict (HEC), authorities in Hambantota have recently launched another large-scale elephant drive, aiming to push elephants from human settlements into designated protected areas.

“With several mega development projects in Hambantota, HEC in the area has gradually increased. We must protect both elephants and humans, so this operation was launched on humanitarian grounds,” said Hambantota district parliamentarian Nihal Galappaththi, who has an important role in the initiative. According to Galappaththi, the drive is led by the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) with the support of the armed forces, farmers’ associations and villagers, counting more than 2,000 people to carry out the elephant drive within a month.

These elephants had lost their body weight due to starvation inside protected areas after being driven into new areas. Image courtesy of CCR.

These elephants had lost their body weight due to starvation inside protected areas after being driven into new areas. Image courtesy of CCR.

Traditional elephant habitat

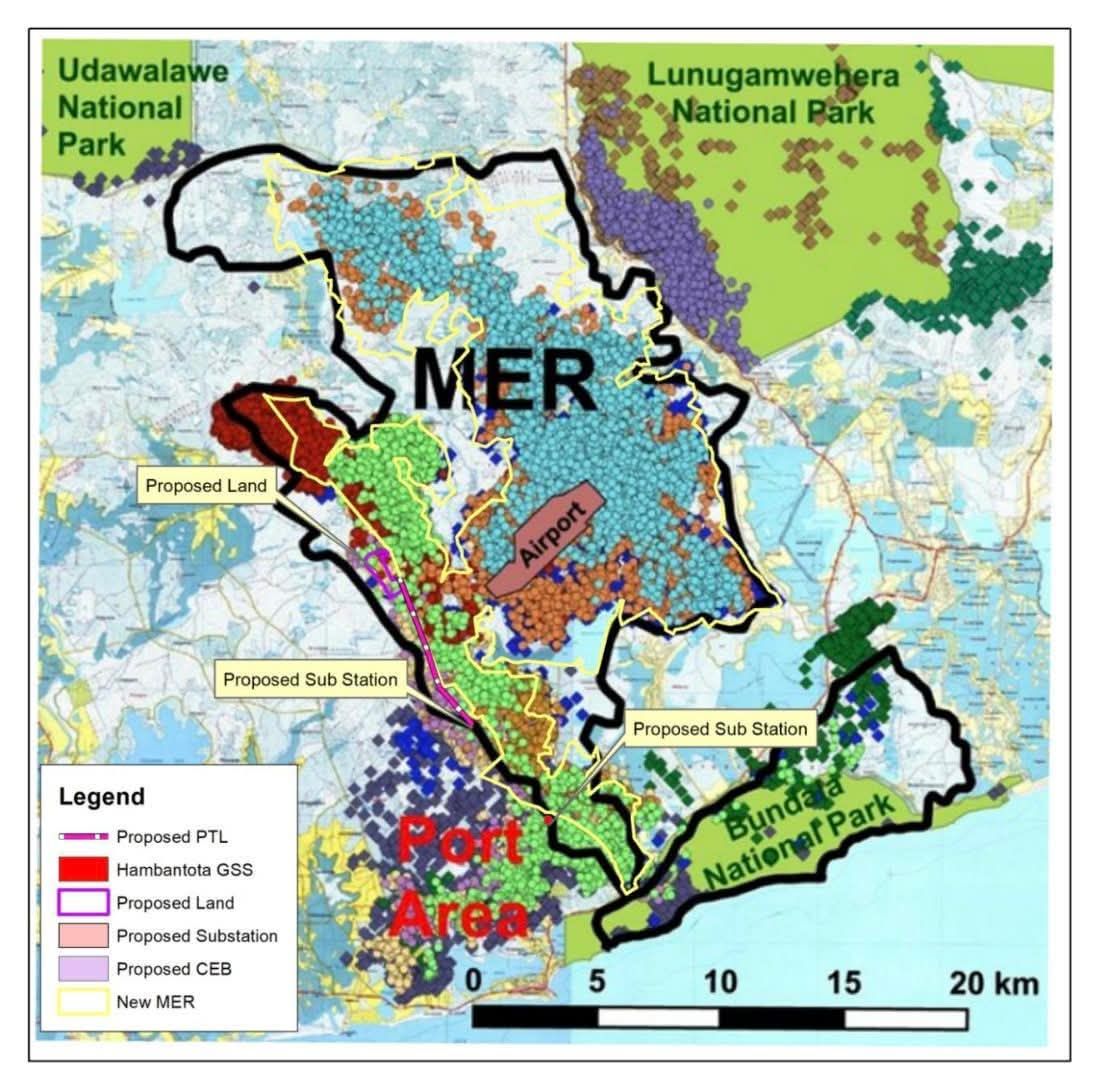

Once an elephant stronghold, Hambantota’s landscape over two decades has drastically transformed itself. The district has several large-scale infrastructure projects, including Sri Lanka’s second international airport, a seaport and industrial zones, all of which have been established by clearing traditional elephant habitats. In response, conservation planners in 2009 proposed a Managed Elephant Range (MER) of about 23,000 hectares (57,000 acres) to reduce conflict and to maintain habitat connectivity across the modified landscape.

Bordering Udawalawe, Lunugamwehera and Bundala national parks, the MER was designed to allow elephants and people to coexist by keeping elephant corridors open rather than forcing animals into restricted spaces. Yet, it took more than a decade to gazette the MER, a task only completed by 2021.

“We are trying to drive the elephants scattered in nearby villages into the MER so they will be able to forage safely and move toward national parks,” said Channa Suraweera, an assistant director of the DWC for the southern region. “About 60 elephants, almost all of them male elephants, are trapped within forest patches near settlements, and these are the ones targeted in the operation,” he said.

However, conservationists strongly oppose elephant drives, calling them outdated, inhumane and counterproductive. Environmental researcher Supun Lahiru Prakash argued that drives often worsen HEC by causing stress to elephants, fragmenting their social groups and displacing them within unfamiliar territory, only for many to return to their home range later. Prakash pointed out that Sri Lanka already possesses a well-researched national action plan for HEC (2020), which discourages the practice of elephant drives and instead calls for community-based electric fencing around villages and cultivated plots.

The makeshift home of 7-year-old Thinuli, along with an inset of her small school bag and books, reflects the deep poverty her family endures where for families like hers, sharing the land with elephants isn’t a choice, but a harsh reality of survival. Image courtesy of Sameera Weerathunga.

The makeshift home of 7-year-old Thinuli, along with an inset of her small school bag and books, reflects the deep poverty her family endures where for families like hers, sharing the land with elephants isn’t a choice, but a harsh reality of survival. Image courtesy of Sameera Weerathunga.

Lacking fodder

“We must first find out why these elephants moved out of the MER region,” said Sameera Weerathunga, elephant researcher of the Udawalawe Elephant Research Project. It is likely due to MER being disturbed by encroachments, where elephants would have less food and water, forcing them to move out in search of new areas,” Weerathunga told Mongabay. If the conditions remain the same in MER, elephants would be forced to move to a new area in search of food, and this may escalate the HEC and extend to new areas, Weerathunga added.

“Farmers in Hambantota cannot do proper cultivations due to this elephant problem where we have to live in constant fear,” said Chandrasena Gamage, a farmer leader who wishes to see the elephants driven away from their villages.

“We do not want to harm the elephants but driven away to a suitable protected area, so that it will serve both people and elephants. Villagers, too, would not have to face the wrath of others for using hundreds of elephant crackers weekly,” Gamage said. The farmer leader also said many environmental activists do not understand the difficulties faced by affected populations and are taking only one-sided action.

Scientific studies do not show elephant drives as a solution, said Prithviraj Fernando, chair of the Centre for Conservation and Research (CCR) and Sri Lanka’s foremost elephant researcher. His long-term studies using GPS-collared elephants have shown that drives rarely succeed. “Elephants have a strong ability to remember locations and tend to return to their home ranges even after being chased long distances,” he explained. “When driven from familiar areas, they become stressed and aggressive, increasing conflict along the way,” he noted.

Radio-collared elephant Biso Menike before (left) and after (right) the drive shows the loss of body conditions due to lack of food. Image courtesy of CCR.

Radio-collared elephant Biso Menike before (left) and after (right) the drive shows the loss of body conditions due to lack of food. Image courtesy of CCR.

Creating new conflict zones

Fernando’s research following the 2006–07 southern elephant drive, an attempt to move hundreds of elephants from Hambantota and adjacent areas to Yala and Lunugamwehera national parks to facilitate an agriculture project, documented the failure of the effort. The lonely males are the usual troublemakers; however, the vast majority driven were females and young elephants, the study recorded. Many elephants returned to their home ranges, while others died of starvation, exhaustion or shooting. Some became stranded in fragmented habitats, creating new conflict zones, according to the study.

Fernando stressed that elephant drives ignore a key ecological reality that more than 70% of Sri Lanka’s elephants live outside the protected areas, depending on landscapes shared with people. “Driving elephants into already full parks is like pouring more water into an overflowing glass where it only spills over,” Fernando said. “The real solution lies in coexistence, land use planning and fencing villages, not pushing elephants away.”

Conservationists also point to a more recent failure of an elephant drive in north-central Sri Lanka. In December 2024, authorities launched another elephant drive to push herds from villages to Wilpattu National Park. But the operation ended prematurely in an area known as Oyamaduwa, where elephants became stranded. Critics say it serves as another example of how elephant drives create new conflicts instead of resolving old ones. However, Sri Lanka doesn’t seem to follow a science-based approach, as a second elephant drive, too, was set in motion in Mahailuppallama in north-central Sri Lanka.

Meanwhile, Hambantota’s current operation is being closely watched by conservationists who fear it may follow the same fate. Decades of failed drives have shown that elephants are resilient and intelligent animals that resist forced relocation. As forests shrink and farmlands expand, both humans and elephants are being squeezed into the same contested spaces.

The Hambantota Managed Elephant Range (MER) was proposed in 2009, designed to balance conservation and development, but was gazetted only in 2021. Image courtesy of the Centre for Conservation and Research (CCR).

The Hambantota Managed Elephant Range (MER) was proposed in 2009, designed to balance conservation and development, but was gazetted only in 2021. Image courtesy of the Centre for Conservation and Research (CCR).

Repeating past mistakes

Fernando’s pioneering elephant studies through radio collaring of the elephants is hailed around the world as landmark studies. But despite having one of the world’s best data sets on Asian elephant behavior and human–elephant conflict, used by other countries to guide their own conservation strategies, Fernando said that Sri Lanka continues to ignore scientific evidence, repeating past mistakes instead of adopting proven solutions.

With Sri Lankan media reporting conflict stories about the drive with some claiming the drive has been halted, Kamal Rohitha Uduwawala, secretary of Sri Lanka’s ministry of Environment, told Mongabay that the elephant drive is going ahead as planned.

The tragedy of little Thinuli and the death of the pregnant elephant reveal the heartbreaking consequences of this ongoing war for space. Yet, amid the grief, the question remains: Will Sri Lanka continue chasing elephants from one corner to another — or finally learn to share the land with these animals based on scientific evidence that supports coexistence?

Banner Image: Elephants were driven to a national park during the final days of the failed elephant drive to Lunugamwehera in Hambantota in Sri Lanka’s deep south in 2006. Image courtesy of Centre for Conservation and Research (CCR).

Citations:

Fernando, P., Jayewardene, J., Prasad, T., Hendavitharana, W., & Pastorini, J. (2011). Current status of Asian elephants in Sri Lanka. Gajah, 35, 93–103. doi:10.5167/uzh-59037

Fernando, P. & Pastorini, J. (2020). Elephant Drives in Sri Lanka. Report, Centre for Conservation and Research, Tissamaharama, Sri Lanka. CCRSL. https://www.ccrsl.org/userobjects/2811_2556_Report-ElephantDrives.pdf