hands on Tenstorrent probably isn’t the first name that springs to mind when it comes to AI infrastructure. But unlike the litany of AI chip startups vying for VC funding and a slice of Nvidia’s pie, Tenstorrent’s chips actually exist outside the lab.

If you’re feeling a little non-conformist and want to color outside the lines, Tenstorrent parts and systems are readily available to anyone that wants them. In fact, you may be surprised to discover the company has already shipped three generations of its RISC-V-based accelerators in an effort to build momentum within the open-source community.

Their philosophy is to deliver a reasonably performant accelerator that can scale efficiently from a single card to a 32-chip system and beyond, at a fraction of the cost of competing AMD or Nvidia GPU boxes.

El Reg recently had the privilege of going hands-on with one of the startup’s most powerful systems to date, an $11,999 liquid-cooled AI workstation called the Blackhole QuietBox. The 80-pound (36 kg) machine is essentially a cut-down version of the chip startup’s upcoming Blackhole Galaxy servers, which are expected next year. It’s designed to serve as a development platform to learn the architecture, port over existing code bases, and optimize model kernels before pushing them to a production system.

And, because the machine uses the same chips, memory, and interconnects that you’ll find in Tenstorrent’s Galaxy servers, that work should theoretically scale seamlessly to the full system — something that isn’t generally true of most AI workstations available today. Sure, you could toss four RTX 5000 Adas or Radeon Pro AI R9700s into a similarly equipped workstation and find yourself in the same ballpark as the QuietBox, but performance characteristics of those systems will be wildly different than the GB200 racks or MI350 boxes your code would eventually end up running on.

This is one of the reasons why Nvidia has periodically released systems like the DGX Station, which cram the same CPUs and GPUs found in its datacenter class products into a more office-friendly chassis. Having said that, we fully expect Nvidia’s next-gen Blackwell Ultra-based DGX Station to cost several times what Tenstorrent is asking for the QuietBox.

If you’re in the market for something to run local AI inference or fine-tuning jobs of small to medium-sized models, Tenstorrent’s QuietBox probably isn’t for you. We expect that will change, but right now the company’s software stack simply isn’t polished enough for most local AI enthusiasts.

However, for machine learning software devs interested in exploring Tenstorrent’s hardware architecture and software stack, or those looking to deploy the startup’s chips in production, systems like Blackhole QuietBox offer a relatively low-cost entry point into the company’s RISC-V-based accelerator ecosystem.

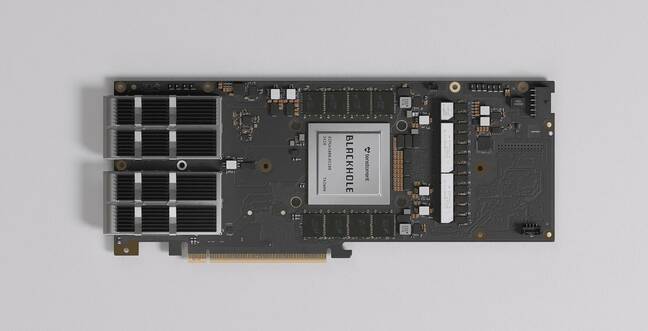

Tenstorrent’s latest QuietBox puts four of its liquid cooled Blackhole ASICs on your desk – Click to enlarge

Tenstorrent’s QuietBox is as beautifully engineered as it is ostentatiously styled. The machine is quiet, but its vibrant blue-stripped livery is anything but. Tenstorrent gets full marks for building a machine that’s instantly recognizable.

The QuietBox, both the Blackhole edition we have here and the older Wormhole-based variant, use a custom chassis with radiator placement and a front-mounted reservoir that remind us of Lian Li’s O11 Dynamic chassis.

The case functions as a chimney that pulls cool air through a 400 mm radiator at the bottom and exhausts it out a second 400 mm rad at the top. That might sound excessive, but those rads have nearly 1,200 watts worth of accelerators, not to mention the CPU, system memory, and storage-generating heat that they also need to dissipate.

The arrangement allows the entire machine to be cooled by just four of Noctua’s 200 mm fans, all while staying true to its name and keeping noise levels in check. And that’s really the inspiration behind the system. Tenstorrent wanted to give its users a high-performance compute platform they wouldn’t mind putting on their desks.

It’s certainly quiet, but it’s not silent. Fan noise ranges from a gentle hum to that of a desktop space heater, which, given the QuietBox’s contents, is an apt description. Accelerator temps never exceeded 70 Celsius in our testing, but that’s because that heat, all 1300-plus watts of it, was being pumped into the room.

We’ve pulled off the side panel to give you a better look at the QuietBox’s internals. – Click to enlarge

Sandwiched between the rads is an Epyc server board from ASRock Rack which provides connectivity to the accelerators as well as a couple of 10 gigabit Ethernet connections for local network access.

Rather than a typical workstation CPU, like an Intel Xeon-W or AMD Threadripper, Tenstorrent opted for the House of Zen’s Epyc Siena 8124P. The 125 watt chip features 16 Zen4C cores — “C” for compact — capable of boosting up to 3 GHz under load.

Instead of a typical workstation CPU, Tenstorrent has opted for a 16-core AMD Epyc. – Click to enlarge

The CPU is fed by eight 64 GB DDR5 4800 RDIMMs (one of the six channels runs in a two DIMM per channel mode) for a total of 512 GB of capacity and just over 200 GB/s of memory bandwidth.

Just below the CPU cold plate, we see the QuietBox’s main attraction: four Tenstorrent Blackhole P150 accelerators. Together the chips boast over 3 petaFLOPS of dense FP8 performance.

The QuietBox’s main attraction is its four liquid-cooled Blackhole P150 accelerators. – Click to enlarge

TT-Quietbox Blackhole at a glance

We couldn’t exactly pull and disassemble one of the P150s from our test system, so here’s a rendering of the card from Tenstorrent’s website. – Click to enlarge

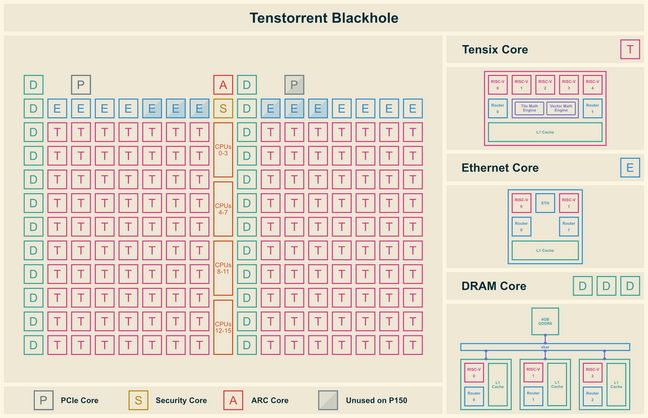

We took a closer look at Tenstorrent’s Blackhole architecture back at HotChips in 2024, but, in a nutshell, each of the 300 watt chips is packed with 752 “baby” RISC-V processor cores that make up everything from the chip’s 140 Tensix processor cores (T) to its memory (D), PCIe (P), and Ethernet (E) controllers.

The chip also features 16 of SiFive’s Intelligence x280 cores, which, in addition to handling operations that can’t easily be parallelized, can run Linux. We weren’t able to test this for ourselves, but in theory this should enable Blackhole to function as a standalone computer.

Here’s an overview of the core layout in Tenstorrent’s Blackhole ASICs – Click to enlarge

Together, the chip’s Tensix cores deliver roughly 774 teraFLOPS of dense FP8 compute or 387 teraFLOPS using Tenstorrent’s four or eight-bit block floating point data types. This compute is paired with 32 GB of GDDR6 that is good for 512 GB/s of memory bandwidth. And there are four of these in the system. But, as you’ll see, actually harnessing that performance and bandwidth proved somewhat difficult.

If dropping nearly $12K on a fully-built system like the QuietBox is a little more than your wallet can handle, Tenstorrent also sells air-cooled (active and passive) versions of the card for $1,399. Or, if you only need one card, a cheaper, less powerful version without the chip-to-chip networking and 28 GB of memory can be had for $999.

BlackHole P100 / P150 speeds and feeds

* not specified for P150c

Scaling

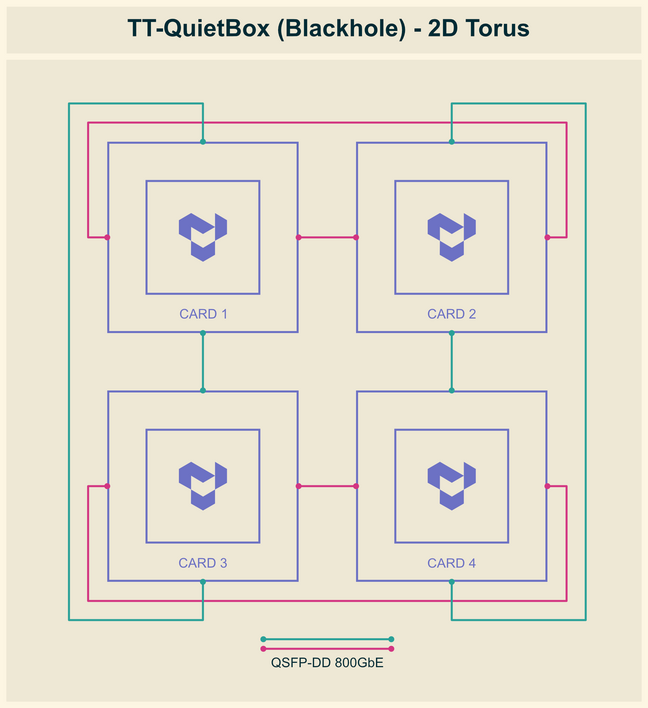

Rather than relying on PCIe 5.0 or some proprietary interconnect like Nvidia’s NVLink, each P150 is equipped with four QSFP-DD cages which provide high-speed connectivity at 800 Gbps to the other cards in the system over Ethernet. Or, well, it’s kind of Ethernet. It appears the ports aren’t exactly standard, with Tenstorrent warning that they are only for chip-to-chip communications, and can’t be connected directly to a switch.

Alongside the motherboard’s rather spartan I/O, we see the sixteen QSFP-DD cages used to mesh the four P150s together. – Click to enlarge

Usually Ethernet isn’t fast enough for scale-up networks, but, with 3,200 Gbps of aggregate bandwidth per accelerator, each P150 has nearly as much interconnect bandwidth as an Nvidia H100 (400 GB/s versus 450 GB/s).

For the QuietBox, Tenstorrent recommends a 2D-Torus topology, like the one depicted below, using the eight 0.5 meter direct attach copper cables included with the system.

For the Blackhole QuietBox, Tenstorrent recommends wiring up the four P150s in a 2D torus – Click to enlarge

While elegant in its simplicity, those cables aren’t cheap, running around $200 apiece. We can’t help but think an NVLink-style bridge connector would have been less expensive. With that said, QSFP-DD means the cards can easily scale to clusters of eight, 16, or more. Want to stitch a couple of QuietBoxes together? That’s totally possible.

More importantly, the architecture means that any code developed on a P150 or QuietBox is directly applicable to larger clusters through various degrees of pipeline, tensor, data, and/or expert parallelism.

In fact, if you look at the P150’s core layout, you’ll notice that only eight of the chip’s 14 Ethernet cores are active. We suspect future versions of the chip will support even larger topologies. Tenstorrent’s Blackhole Galaxy, for example, will pack 32 accelerators arranged into a 4×8 mesh.

Blackhole Galaxy is expected to deliver about 25 petaFLOPS of dense FP8 performance, a terabyte of GDDR6, and 16 TB/s of aggregate bandwidth. To put that in perspective, a DGX H100 with eight GPUs offered just under 16 petaFLOPS of dense FP8 performance, 640 GB of HBM3e, but 26.8 TB/s of memory bandwidth. Nvidia’s Blackwell and AMD’s MI350-series systems are on another level and are priced as such.

But, that’s for a single node. Tenstorrent’s interconnect heavy architecture means that it could be scaled up to a rack or beyond. In a rack-scale configuration, we can envision a system with 192 accelerators. Add in some optical transceivers to boost the reach, and the platform could theoretically scale across multiple racks and thousands of accelerators.

This is really what the startup is getting at when they call Blackhole infinitely scalable. In fact, the architecture is really more in line with how Google and Amazon have built out their TPU and Trainium clusters than what we see with Nvidia hardware.

Initial setup

Setting up the QuietBox is a bit different than configuring your typical desktop or workstation.

For one, there’s no graphics card — at least not in the traditional sense. Instead, your options are either to use the motherboard graphics via the included VGA-to-HDMI adapter, or the system’s IPMI interface to control it remotely over the network.

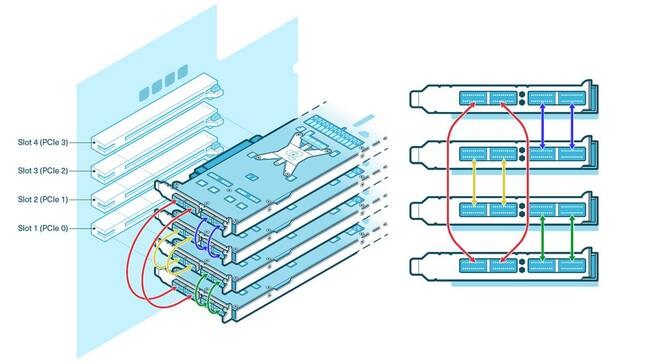

There’s also the matter of wiring up the accelerators per the diagram below.

The QuietBox’s four P150s use eight 800GbE DACs connected as shown in the diagram above – Click to enlarge

With that out of the way, we could power up the system. Tenstorrent notes the initial boot could take in excess of 10 minutes. This is normal for Epyc systems, particularly those equipped with a large quantity of memory, but it’s something that may catch newcomers off guard, making Tenstorrent’s warning warranted.

Out of the box, the machine comes preinstalled with Ubuntu Desktop 22.04 LTS. Since we knew all of our interaction with the system would be through the terminal, we opted to install OpenSSH, so we could remotely access it over the network.

Tenstorrent provides an automated install script which ensures that all the dependencies are installed, device firmware is fully up to date, and the Ethernet mesh connecting the cards is functioning properly.

For the most part, the script involves answering a few “Yes / No” questions, most of which you’ll be answering “Yes” to. Unfortunately, on our initial setup, a recent change to package naming caused it to error out.

This, as it turns out, was foreshadowing as to the rest of Tenstorrent’s software stack.

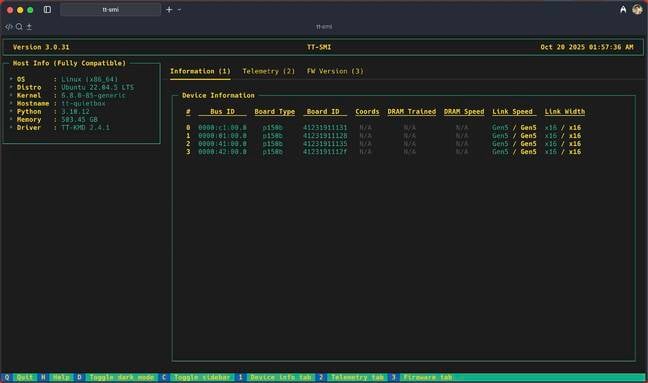

In any case, after a reboot, which took another eight or so minutes, we ran Tenstorrent’s diagnostics utility tt-smi and confirmed all of the cards were detected properly.

Tesntorrent’s system management interface tt-smi was quite sure what to make of our single chip Blackhole accelerators – Click to enlarge

All four of the cards appeared as expected, but it’s clear `tt-smi` isn’t quite sure what to make of our Blackhole cards. In addition to being detected as Tenstorrent’s passively-cooled P150b parts, many of TT-SMI’s fields were either blank or missing. This was a bit disconcerting, but apparently it’s normal and nothing to worry about.

Model demos

Blackhole isn’t a GPU. That means you can’t just spin up a model in something like Ollama or Llama.cpp like you normally would. Thankfully, Tenstorrent’s getting started guide provides a number of demos, including one for running LLMs in TT-Inference-Server.

This process was fairly straightforward and was aided by a couple of convenient helper scripts that automatically selected the right model and flags for the hardware.

The entire process took about 45 minutes or so. Most of the wait was dominated by the download of the roughly 140 GB model files and conversion to the 4- and 8-bit block floating point data types used by Tenstorrent’s hardware.

In the end, we were left with an OpenAI-compatible API endpoint that we could point to a front-end, like Open WebUI, at and begin prompting the system.

Since LLM inference is one of the prime use cases for this class of hardware, it’s nice to see Tenstorrent putting the documentation for TT-Inference-Server front and center, even if performance isn’t quite there yet.

Alongside the LLM serving demo, Tenstorrent also provides a containerized environment for playing with model demos that can be started by running `tt-metallium-demos`.

This eliminates the often frustrating process of downloading and wrangling the dependencies necessary to get things running. With a bit of effort, we were able to get a variety of models running, including Resnet50, Bert, Stable Diffusion 1.4, and the Boltz 2 structured biology foundation model, which is designed to predict protein structure and binding characteristics.

In addition to ML demos you’d expect, like Bert or ResNet, we were also able to get scentific models like the Boltz-2 biomolecular foundation model running on the QuietBox – Click to enlarge

Unfortunately, actually finding the demos requires digging through Tenstorrent’s TT-Metal Github repo. Even after we found them, it was hit or miss whether they ran at all or if there was any documentation to help us sort out why.

We’d really like to see more playbooks and tutorials like Tenstorrent’s LLM serving guide for popular genAI workloads like image generation, text and image classification, object detection, voice transcription, and fine tuning, to name a few.

New users shouldn’t need to search through GitHub repos or parse code comments just to get demos running. A couple of straightforward and user-friendly tutorials would go a long way to attracting interest from developers and students. It would also give Tenstorrent the chance to highlight its hardware’s strengths, which aren’t always obvious given the general immaturity of the software stack.

Tenstorrent’s software philosophy

Something that’s become abundantly clear over the past few years is that it doesn’t matter how good your GPU or AI ASIC looks on paper if nobody can or is willing to program it.

Tenstorrent has taken a multi-pronged approach to this particular challenge. First, its software stack is entirely open source. Second, it’s developing both a low-level API interface akin to Nvidia’s CUDA and higher-level compilers for running existing Pytorch, JAX, or Onnx models.

This sets Tenstorrent apart from many AI chip startups that may have aspired to such a comprehensive software stack at first, but in the end delivered little more than an LLM inference server or API service.

Tenstorrent’s software strategy looks a bit like a layer cake. – Click to enlarge

At the very bottom of Tenstorrent’s software stack is its low-level kernel environment (TT-LLK), which is about as close to programming on bare metal as you can get.

One layer up from that is TT-Metalium (TT-Metal) which provides a low-level API for writing custom kernels in C or C++ for Tenstorrent hardware. You can think of TT-Metal in the same category as Nvidia’s CUDA or AMD’s HIP. But while TT-Metal offers low-level access to hardware features, it comes at the price of a new programming model.

Above TT-Metal is TT-NN, a library that exposes supported neural-network operations to users without requiring intimate knowledge of the underlying hardware. These libraries work with both standard Python and C++ and provide a higher-level program environment for running AI models.

From what we can tell, TT-Metal and TT-NN is where most of Tenstorrent’s model enablement is taking place. For example, both Tenstorrent’s implementation of Transformers and vLLM are running atop TT-NN.

The complexity associated with programming at these layers is no doubt why it has taken so long to add support for new models, as custom kernels need to be handwritten for each.

These challenges aren’t unique to Tenstorrent. It’s one of the reasons why PyTorch, TensorFlow, and JAX have become so popular in recent years. They provide a hardware-agnostic abstraction layer for accelerated computing.

However, because Blackhole doesn’t look anything like a modern GPU, using these same frameworks means Tenstorrent needs a compiler.

The company is developing a multi-level intermediate representation (TT-MLIR)-based compiler it calls Forge. The idea is that TT-Forge will take PyTorch, JAX, or other models and convert them to an intermediate representation. TT-Metal can then use this to compile compatible kernels for the underlying hardware.

Forge is currently in beta and clearly under very active development. If they can make it work, TT-MLIR and Forge should eliminate the need to hand code custom kernels just to support new models. As we’ve seen with similar projects, performance probably won’t be as good as targeting TT-NN or TT-Metal, but would go a long way to expanding Tenstorrent’s addressable market.

Gen AI performance

The Tenstorrent Blackhole accelerators available today, including the QuietBox, are all development kits, and that makes performance comparisons a bit tricky. The point of this hardware isn’t to compete directly with Nvidia or AMD GPUs, at least not just yet, but rather to enable users to write software for Tenstorrent hardware.

The state of the startup’s software stack means performance enhancements are hitting Github on a daily basis. Just like we saw with AMD’s ROCm 6.0 libraries, software can have a far larger impact on inference and training performance than the hardware itself. In a little over a year and a half, AMD managed to bolster inference performance on the MI300X by 3x. We fully expect Tenstorrent to deliver similar gains with time.

But this means any benchmarks we share here will already be out of date. As such, the figures below should be interpreted as a snapshot of the Blackhole P150 and QuietBox’s performance as of November 2025 and not as the final word on what the accelerators are capable of.

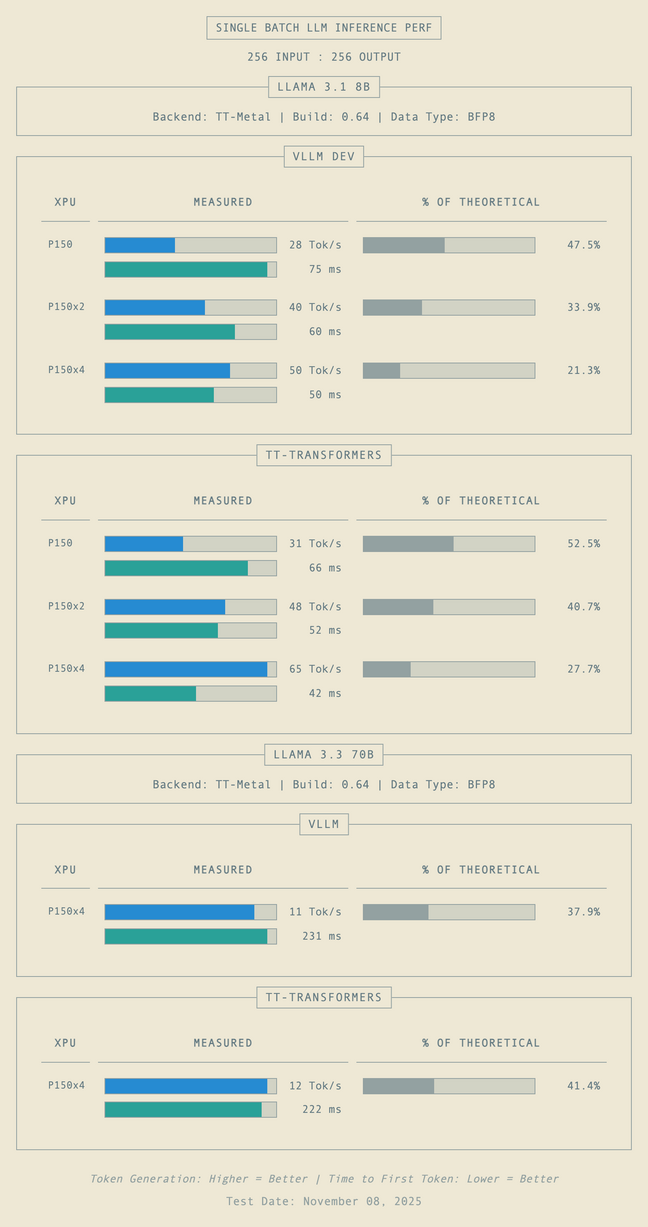

LLM inference performance

For the Blackhole accelerators, we tested LLM performance using both the TT-Transformers libraries and Tenstorrent’s vLLM fork. We also experimented with TT-Inference-Server, but found no material advantage over using vLLM.

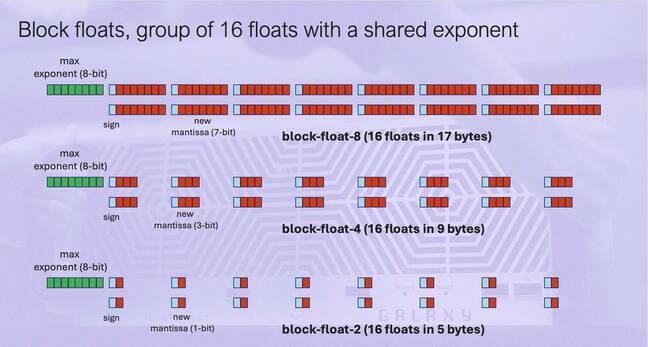

For most LLM inference workloads, Tenstorrent utilizes either 4- or 8-bit block floating point data types, not unlike OCP’s MXFP4 and MXFP8 or Nvidia’s NVFP4, which we previously explored here.

The implementation of these data types is, unfortunately, non-standard. We can’t just pull an NVFP4 quant from Hugging Face and expect it to run. Instead, we needed to quantize higher-precision models to run on the QuietBox’s P150s. When it comes to AI, quantization involves compressing model weights from one precision to another, shrinking them in the process.

Tenstorrent’s accelerators are optimized for block floating point datatypes similar to what we’ve seen from OCP and Nvidia – Click to enlarge

The specific combination of FP8, BF16, BFP8, and BFP4 used by Tenstorrent varies from model to model in order to balance performance and accuracy.

For the sake of consistency, we opted to quantize our test models, which included Llama 3.1 8B and Llama 3.3 70B, to BFP8. In real world applications, we recommend sticking to Tenstorrent’s defaults.

And, if you’re wondering, we’re using Llama rather than newer, more capable models like gpt-oss-20B or 120B. The reason is simple: of the rather short list of LLMs supported, the two Llamas appear to be the best optimized for Blackhole.

A full list of supported models can be found here.

Batch 1 performance

We began our testing by evaluating the single batch performance of the P150 in single, two-way and four-way tensor parallel configurations.

Tensor parallelism is a method of distributing both the model weights and inference workload across multiple accelerators. It generally provides better scaling than pipeline parallelism, while also being more memory efficient than data parallelism.

On the left, we see the decode and prefill performance shown in blue and green, respectively. If you’re not familiar, decode represents how fast the hardware can generate tokens, while prefill measures the time required to process a prompt.

On the right, we chart how efficiently the inference engine can utilize the card’s memory bandwidth as a percentage of its peak theoretical performance.

On the left we chart decode and prefill performance in Tok/s and miliseconds time to first token. On the left we chart the percentage of theoretical decode performance achieved – Click to enlarge

Even in the best-case scenarios, the P150’s decode performance is only about half that of theoretical when running Llama 3.1 8B on a single card. This is far less than we typically see on GPUs from Nvidia or AMD, which usually saturate somewhere between 60 and 80 percent of a card’s memory bandwidth.

For the larger 70 billion parameter model, which is too large at BFP8 to run on one or even two cards, the QuietBox scales significantly better but still only manages to achieve about 41 percent of peak theoretical performance.

Scaling up

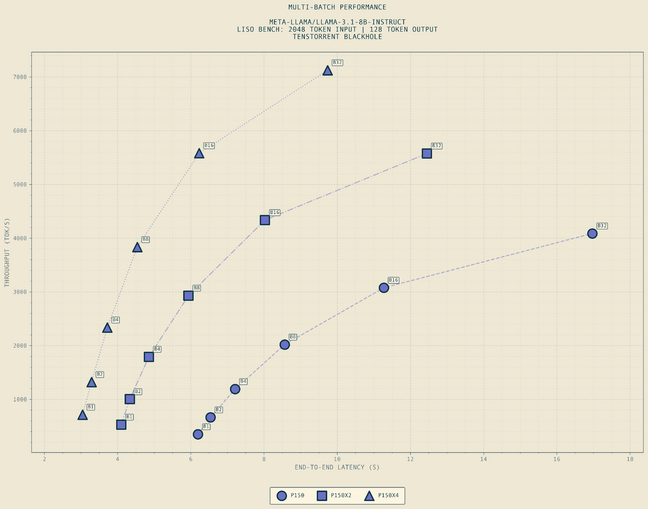

Sometimes accelerators perform better at larger batch sizes. To test this, we tasked the system with processing a 2,048-token prompt and generating a 128-token response at batch sizes ranging from 1 to 32. At the largest batch size, the cards had to process more than 64,000 tokens and generate roughly 4,096 tokens in response.

Like our batch-one benchmarks, we ran these tests across our P150s in single, dual, and quad tensor-parallel configurations, charting total token throughput on the vertical axis and end-to-end latency on the horizontal.

This graph charts overall throughput (tok/s) against end-to-end latency at various batch sizes ranging from 1-32 – Click to enlarge

Even at higher batch sizes, performance fell well short of our expectations. At batch 32, results showed a roughly 25 percent reduction in end-to-end latency going from one card to two and then again from two cards to four. Meanwhile, overall throughput jumped 36 percent going from one P150 to two, and 27 percent going from two to four.

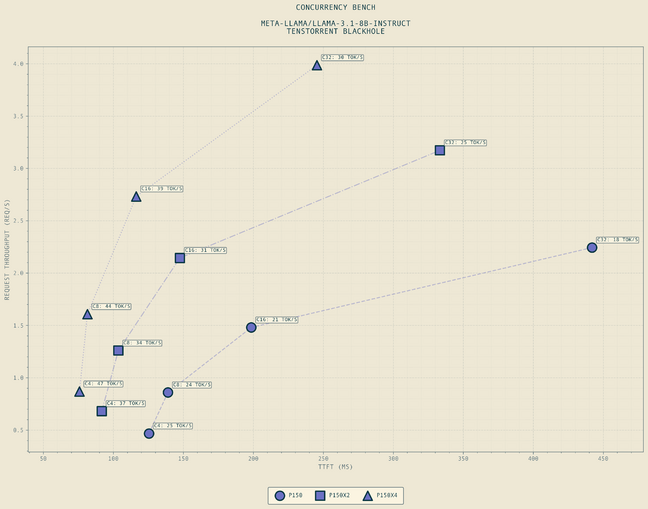

We observed similar scaling in our online-serving benchmark. The four-card configuration was able to serve 1.78x more requests than a single P150, while the dual-card configuration landed roughly in the middle.

Similar to the multi-batch benchmark, this graph depicts the performance characteristics for various numbers of concurrent requests – Click to enlarge

At four requests a second, a QuietBox running a similarly-sized model should be able to handle over 14,000 requests an hour while maintaining reasonable prompt processing times (TTFT) and interactivity. Performance isn’t awful; it’s just less than half of what we’d expect from hardware of this caliber.

The relatively even spacing in both tests is encouraging in its consistency, but performance is anything but. We would have expected better scaling here, especially considering the 12.8 Tbps of bandwidth stitching the cards together.

To put these performance figures into perspective, a single P150 performed almost identically to an Nvidia DGX Spark in our testing. Going off speeds and feeds, the Blackhole card should deliver somewhere between 2-3x the the performance in LLM serving at FP8.

Confusingly, Tenstorrent’s own docs actually show super-linear decode scaling on its prior-gen accelerators when going from an eight-chip Wormhole QuietBox to a 32-chip Galaxy node. Meanwhile, for prefill, the jump from eight to 32 accelerators cut prompt processing time by roughly two thirds. This suggests that a lack of optimization is holding back the P150 and QuietBox from achieving its full potential.

Tenstorrent’s own performance testing shows that it was able to achieve linear decode scaling on its prior gen Wormhole accelerators – Click to enlarge

Making sense of Blackhole’s half-baked performance

So, what’s with the lackluster showing for Tenstorrent’s latest accelerators? From what we can tell, the problem lies in the fact that all the models we tested appear to be using kernels written for its older Wormhole accelerators.

These models are forward-compatible with Blackhole, which means they run but don’t take advantage of the newer chip’s substantially higher core counts.

Wormhole features 80 Tensix cores, but, on the N150 and N300, only 72 or 128 (64 per ASIC) are actually enabled. In what we imagine was a move to maximize compatibility, most models ended up being tuned for 64 Tensix cores. Unfortunately, that means, when running kernels written for Wormhole on Blackhole, 76 of the chip’s 140 Tensix cores end up sitting idle.

The lack of optimized kernels also appears to be why Blackhole generates tokens so much slower than we’re expecting. The kernels haven’t been tuned to take advantage of the additional memory bandwidth, so they don’t. The decode performance we observed is indicative of a card artificially capped at 288 GB/s of bandwidth, which happens to be exactly what Wormhole was capable of.

If we’re right, this is a missed opportunity on Tenstorrent’s part. We understand that this is a bit of a chicken and egg problem. You can’t exactly write kernels if you don’t have the hardware to write them for. But even one optimized model would have been enough to showcase Blackhole’s architectural improvements.

Instead, we’re left with an accelerator that, in testing, looks like it only delivers iterative improvements in performance over its predecessor while consuming roughly twice the power.

We get the distinct impression here that, in a rush to get the product out the door, Tenstorrent’s marketing team may have gotten ahead of its software engineers.

Summing up

With the Blackhole QuietBox, Tenstorrent has managed to build a powerful. yet quiet, not to mention relatively affordable, development platform for its latest generation of accelerators.

On paper, the system’s four Blackhole P150s promise a nice balance of compute, memory, and bandwidth, while doing something similarly priced GPUs can’t: scale. The days of NVLink on consumer or workstation platforms are long past us, and PCIe will only get you so far. With 3.2 Tbps of bandwidth per chip, Tenstorrent has a platform that should deliver the same linear scaling as its last-gen Wormhole cards.

While some will balk at the machine’s $11,999 price tag, getting anything remotely close in terms of performance, memory, and networking will set you back at least as much, if not more.

The bigger problem for Tenstorrent is that those competing platforms are still more useful and therefore a better value thanks to software stacks that are more mature, even if they can’t scale as effectively.

The open source community — arguably the P150’s and QuietBox’s target market — can and are helping with this, but, without clear examples to demonstrate the Blackhole architecture’s potential, it’s a tough sell.

Imagine if Nvidia launched a new GPU with 3x the performance and nearly twice the memory bandwidth, but to harness any of it meant rewriting your codebase without any assurances the claimed performance gains are even achievable. That’s a big ask. Yet, this is essentially where we find ourselves with Blackhole.

The lack of optimized kernels for LLM inference — the most important, or at least highest demand, workload in the world today — is a particularly inexcusable misstep, and one that Tenstorrent shouldn’t waste time resolving.

Even one optimized model, perhaps OpenAI’s gpt-oss, would go a long way toward inspiring confidence, and, more importantly, building momentum behind the Blackhole architecture.

On the topic of software, we would also like to see Tenstorrent do a better job of consolidating its documentation. As it stands, the company’s docs are scattered across multiple dedicated sites or buried in one of dozens of poorly indexed GitHub repos.

In particular, we think Tenstorrent would benefit greatly from increasing the number and quality of its “Getting Started” guides. If anyone from Tenstorrent’s software team needs inspiration, take a look at the documentation Nvidia has provided with the DGX Spark.

The more things that potential customers know can and do run on Tenstorrent hardware, the faster the company can build momentum behind the product, and the easier time it’s going to have selling accelerators and core IP.

Production servers based on Tenstorrent’s Blackhole architecture haven’t started shipping, so there’s still time for the startup to break out the sanders and polishing cloths and smooth over its software platform’s rough edges. ®