European leaders’ failures on Ukraine are one more grim staging post on their road towards irrelevance

During the furious debates that raged over Brexit in the UK in 2016, Leavers demonised the European Union as a Leviathan of gigantic strength which was robbing the UK of control over its own affairs.

Remainers argued that, on the contrary, the UK was far stronger belonging to one of the greatest power blocs in the world, giving the British people greater commercial opportunities and political influence than they might otherwise possess.

Eight years on, both the malign and benign images of the EU’s power for good or evil have turned out to be delusory. In a decade marked by ferocious wars in Europe and elsewhere, and by escalating conflicts with the US over trade, the EU states individually and collectively have been shown to wield astonishingly limited clout, punching far below their weight.

A humiliating blindside

A week ago, European leaders were scurrying about in a panic when they discovered to their horror that once again they had been ignored by the US and Russia in formulating a peace plan to end the war in Ukraine. Their blindsiding was all the more humiliating given that the war is being fought on European soil, and that the Europeans are paying for American weapons – which enable Ukraine to keep fighting Russia.

Even this humbling lack of leverage on the Ukraine war was dwarfed by another EU failure to exert its strength this summer. As the world’s largest trading bloc, it might have expected to negotiate on an equal footing with President Donald Trump over his imposition of higher tariffs on the EU. But on 27 July, the President of the EU Commission Ursula von der Leyen nailed a white flag to the EU mast by agreeing at Trump’s Turnberry golf course in Scotland to a 15 per cent rise in US tariffs on EU exports without any proportionate EU tariffs on American goods.

“It is a dark day when an alliance of free peoples, brought together to affirm their common values and to defend their common interests, resigns itself to submission,” complained French prime minister Francois Bayrou.

Repeatedly ignored

When it comes to international decision-making, the EU, often accompanied by ex-EU member Britain, is being repeatedly ignored. At the UN Climate conference just ended in Brazil, the EU, UK and other states demanded “a road map” towards getting rid of fossil fuels, only to find that opposition by oil, gas and coal producers – led by Saudi Arabia and Russia – had even dropped the words “fossil fuels” from the text of the final communique.

The implosion of the EU as a global influencer is dramatic, though some argue that all we are seeing is the unmasking of the organisation’s pre-existing weakness. The decline is not solely in terms of realpolitik. Once, Remainers in the UK believed – and possibly still do – that the EU was the staunchest defender of liberalism, democracy and the spirit of rationality in human affairs which originated in the 18th century European Enlightenment. Yet, during two years of mass slaughter by Israel of Palestinians in Gaza – including at least 20,000 children – the EU was ineffectual to the point of complicity with what much of the world views as a merciless genocide. Any future bid by the EU to lay claim to the moral high ground in any conflict will be derided as gross hypocrisy.

Far from being a power-hungry autocracy in the making, as Leavers claimed, or a bastion of rules-based democracy as Remainers believed, the EU – with the UK obediently trotting behind – has turned out to be a busted flush.

Too fragmented to decide anything

Instead of uniting all that was politically, economically and morally best in Europe, it has exposed itself as a self-important talking shop, an updated version of the old Holy Roman Empire, the ramshackle central European alliance which, from the Middle Ages to Napoleon, was too fragmented to decide anything.

When push came to shove – and the pushing and shoving in the world today is far greater than 10 years ago – the EU, and Nato for that matter, do not possess the will and the unity for concerted action. A smokescreen generated by ceaseless rounds of meetings masks impotence when it comes to the defence of Ukrainian sovereignty and other serious issues. Sir Keir Starmer is comically proud of his “coalition of the willing”, though what its members are willing or unwilling to do remains a mystery. The tired old jibe about the rest of Europe being “willing to fight to the last Ukrainian” contains an essential truth.

Why has the EU proved such a disappointment? Why have the European elites been so visibly incapable of dealing with the challenges facing them since the financial crash of 2008? European integration has always been a bit of a phoney, as the nation state never ceased to be the decisive unit on the international map. Charles de Gaulle was right to talk about a “Europe des patries”, old hat though the idea of the primacy of national governments may have seemed in the 1960s. At the time of Brexit, a former British diplomat whom I had imagined would be a natural Remainer told me “there are too many people in European think-tanks and universities studying European integration and far too few looking at disintegration. That is going to be the wave of the future.”

Geography and traditions matter

The weaknesses of the EU should long have been obvious. Nations may delegate trade and regulations, but not, if they have any sense, decisions on war and peace. The very size of the EU and Nato make them unwieldy. Geography and traditions matter. Poles and Estonians, historic enemies of Russia, will perceive the Russian threat differently from Spanish and French. Nobody likes to get killed in the interests of another nation. “Who will die for Danzig?” was a French anti-war slogan in 1939. The same is probably true of Kyiv.

For most Europeans today the Ukraine war has been a propaganda conflict. People have strong views, usually demonising Russia, but they have so far had to pay no “butcher’s bill” in corpses and mangled survivors coming home from the front. As a result, there is a dangerous European disconnect with the military situation on the ground, the battlefield reality, which will be the final decider for any successful peace agreement.

Trump and the US military reportedly believe, based on intelligence analyses, that Ukraine is slowly losing an attritional war with casualty and desertion rates soaring. Drone warfare makes it impossible to supply frontline troops with sufficient food and ammunition, or to reach the wounded to give them medical treatment. Doubtless the Russians suffer equally, but they are much the larger population and they believe the military balance will tip further towards them in six months or a year’s time.

European leaders speak and act as if Ukraine is winning the war, though I doubt if many of them really believe this. They seldom mention the appalling death toll, though Trump speaks continually about 7,000 Ukrainians and Russian soldiers being killed every week. Many of Trump’s statistics are false, but, unfortunately, probably not this one.

The failure of European leaders to contribute significantly towards ending this slaughterhouse on their own continent marks one more grim staging post on Europe’s road towards global irrelevance.

Further thoughts

I gave the below speech on 25 November at a memorial meeting for David Hirst (1936-2025), one of the greatest journalists of his era, who was for 45 years The Guardian‘s correspondent in Beirut:

I first met David in the late 1970s in Beirut and I would meet him there or elsewhere in the Middle East over the following decades. Regardless of his or my location, I was continually conscious of his presence as I read everything he wrote – to be better informed, naturally, but also for more egocentric motives. I knew that David was more likely than any other journalist in the Middle East to have written something I truly wished I had written myself.

What made me grind my teeth a little was not so much his scoops, though he had plenty of those, but rather articles he had written about people and places I knew well. But when I read what David had written, I could often see that he had drilled that bit deeper and reached conclusions more definitive and striking than myself.

I remember one incident when I was correspondent for The Independent in Jerusalem in the late 1990s. I had visited Gaza and found that the newly established Palestinian Authority was making a terrible mess in running the place because of Israeli pressure – but also because of its incompetence and corruption. I had described this in several pieces, but then I read with some envy an excoriating three-part series by David about Gaza. Backed by incontrovertible evidence of wrongdoing, every elegantly written paragraph carried a punch with devastating impact.

The influence of these pieces in the Middle East and beyond was all the greater because of his strong support for the Palestinian people during the escalating horrors inflicted on them for decade after decade. In 1977, he first published The Gun and The Olive Branch: the Roots of Violence in the Middle East, which he repeatedly updated and which remains one of the best histories of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Though a lowkey person in many respects, David never lost his capacity for outrage at terrible injustices – whoever committed them.

Rather than me listing the virtues of the book, I think it might be more telling – and amusing – if I quote from a critical review of it that appeared in the Washington Post, when it first came out nearly half a century ago. Here it is:

“The Gun and the Olive Branch could not appear at a more inappropriate time,” concluded the WP reviewer Roderick MacLeish. “A few weeks before its publication Anwar Sadat of Egypt and Menachim Begin tried to break out of the miserable point-counterpoint of Middle Eastern history. Their Jerusalem meeting conceded that there can be no adequate retribution for all the things that Abraham’s descendants have done to each other, for all the things that others have done to them. The only possible vision is forward.

“In the light of that moment, David Hirst’s book is an accusative sniffle amid the opening chords of an anthem of hope.”

Because he refused to join in what might be better termed an anthem of illusion and deception, David made many enemies – invariably the right kind of enemies to have, but dangerous people all the same. For many years he believed – and I thought the same – that the Sunday Times Middle East correspondent David Holden, who was murdered on arriving in Cairo from Beirut in 1977, might have been killed in mistake for himself because of similar names. David – Hirst that is – had been writing a very negative biography of Sadat at the time.

A few years later, I witnessed an incident which shows how David was unintimidated by powerful and dangerous people. Both of us were in a party of a dozen or so foreign journalists who had been unexpectedly given visas to go to Iraq. It turned out that Saddam Hussein wanted to give a press conference, which took place in a hall in Baghdad with a stage. After we sat down, alongside many Iraqi journalists, the presidential guard arrived and we assumed that Saddam must be in the building.

An hour or more passed and the press conference failed to begin. A few of us tried to leave, but were pushed back by the presidential guards. It turned out that the microphone was not working, something which Saddam felt reflected badly on Iraq. He refused to begin the press conference until it was fixed.

After a further lengthy wait this was done and Saddam appeared accompanied by an English-Arabic translator. Respectful questions were asked of the Iraqi leader by the Iraqi media and duly answered by him. Then the foreign journalists started asking questions in English which were duly translated in Arabic. Suddenly I heard a yell of dissent and somebody appeared to be shouting furiously at Saddam and his translator, something unheard of in Iraq, where even whispered criticism of Saddam might have lethal consequences.

I was sitting some seats away, but I saw that the person doing the shouting was David, on his feet and gesticulating with his arms. He had asked some trenchant question of Saddam in English, which the translator, presumably terrified of repeating David’s critical words, had drastically toned into a more palatable and craven form for Saddam. The Iraqi leader had just begun to reply when David, who had understood the deliberate Arabic mistranslation, vigorously objected and demanded a retranslation – which to our surprise, he eventually extracted.

He was unafraid, modest, high principled, deeply knowledgeable, and had great professional writing skills; a person who always sided effectively, though never uncritically, with the small and weak battalions against big and powerful ones.

He was a great journalist.

Beneath the Radar

What do Starmer and Jeremy Corbyn have in common, aside from being unsuccessful leaders of the Labour Party? Both appear to be fairly decent people, so why have they attracted such a degree of unpopularity – and even hatred – beyond anything merited by their flaws?

I suspect that, in an age of myriad news outlets, when a successful political leader needs to give around the clock press conferences and interviews – witness President Donald Trump, New York mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani and UK Green Party leader Zack Polanski – they are fatally hobbled by their inarticulacy in front of a camera or before a hostile interviewer. Both Corbyn and Starmer lack the political and media instincts of Trump and Mamdani, so impressively displayed at their notorious joint press conference in the Oval Office.

Trump and Mamdani think much like journalists, knowing what will make a headline and what will not. They never let a vacuum of information develop about themselves and their views which can be filled by their enemies. Their talents are not new, but the penalties for not being able to do this have soared, as Starmer and Corbyn discovered to their cost. Building a personality cult has become much easier, but so too has becoming the victim of instant demonisation.

Cockburn’s Picks

As the new Syrian leader, Ahmed al-Sharaa, formerly a leading member of al-Qaeda, is received in the White House, there is not much news about the ongoing massacres of Syrian minorities – Alawites, Druze and Christians – though the great French expert on Syria, Fabrice Balanche, describes what is going on. The Syrian Kurds fear they may share the same fate.

I always saw the Syrian civil war (2011-24) as being primarily between the Sunni Arabs and the Syrian minorities led by the Alawite Assad family. The Assads held power by brute force, and their community is now the price for this. Here is an excerpt from Balanche’s account:

“Since March of last year, there has not been a single day without news of an Alawite being murdered or gone missing. Young men live in constant fear, desperate to escape. Women are abducted, then forced to marry jihadists, claiming that they willingly joined their husbands after appearing wearing a niqab. Families keep quiet because of shame, but also out of fear of reprisals.”

I used to stay in hotels in the Christian quarter of the Old City of Damascus, where the alleyways leading to my hotel were too narrow for car bombs. Under the Assads, Syria was a ferocious authoritarian state, but I enjoyed its ethnic and religious diversity – something which is now being extinguished forever.

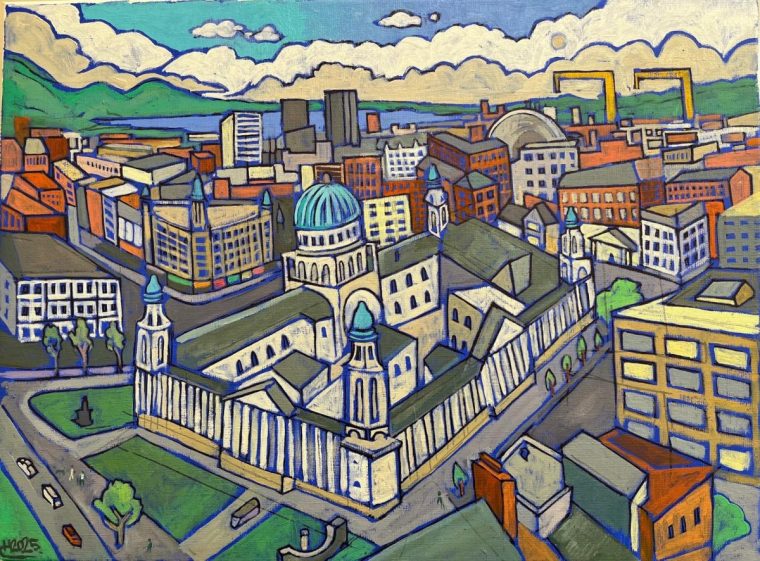

I have written a series of essays, illustrated by my son Henry, about the state of the UK. You can read my dispatch from Northern Ireland here; Lewes here; Canterbury here; Dover here; Newcastle here; Herefordshire here; Salford here; and Barrow here. Patrick has also written an essay about the gig economy, which you can read here.

Belfast, illustration by Henry Cockburn

Belfast, illustration by Henry Cockburn