National

Saturday, 29 November 2025

An obsession with the blue-and-white tiles led to Rembrandt’s house in Amsterdam, before modern technology brought the ceramic designs closer to home

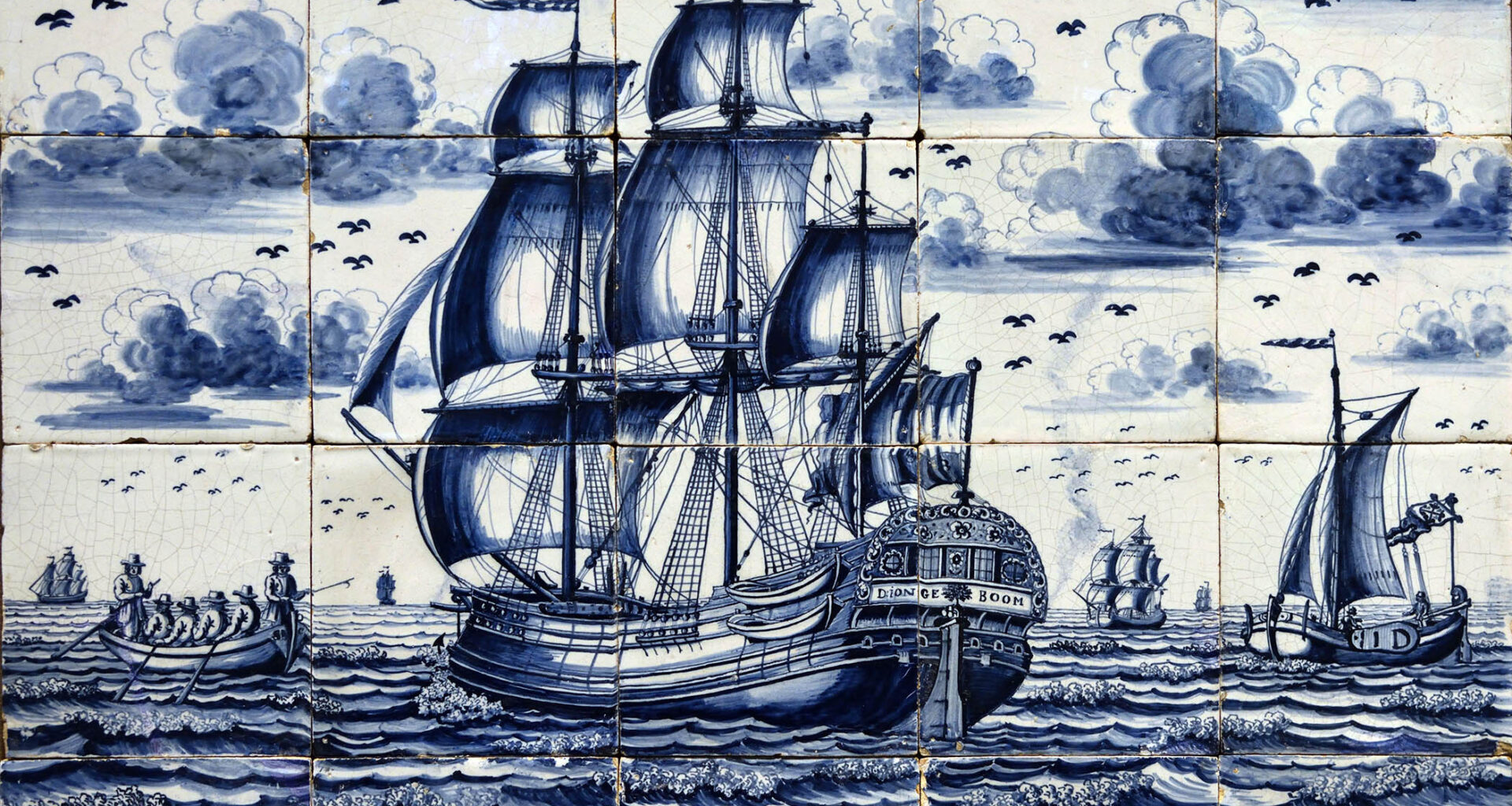

A tile design of the whaler De Jonge Boom by Dutch painter Pals Karsten, circa 1775. Alamy

They started arriving in small, deceptively heavy square parcels, sometimes chipped or cracked, some still clinging to bits of wall.

The packages grew with my husband’s online buying confidence and enthusiasm, although he insisted he was restricting himself to no more than £10 a tile.

My husband’s Delft tile mania was unleashed by his most reckless online auction purchase to date: a wrecked 14th-century merchant’s house in King’s Lynn, west Norfolk. When we learned the house had belonged to a Dutch merchant called Jakob Van Flierden, and then his son, between 1700 and 1750, the collecting began in earnest.

Dutch landscapes feel familiar to the residents of East Anglia’s flat wet expanses, so we hopped over the North Sea for some inspiration. We saw Delft tiles in canal houses, as glorious expanses on chimney breasts, and trompe l’œil designs on kitchen walls, but it was their use as skirting boards and around the bottom of staircases that really made us swoon. (We need to get out more, clearly.)

Modern tiles created using AI for Malika Browne’s Norfolk home.

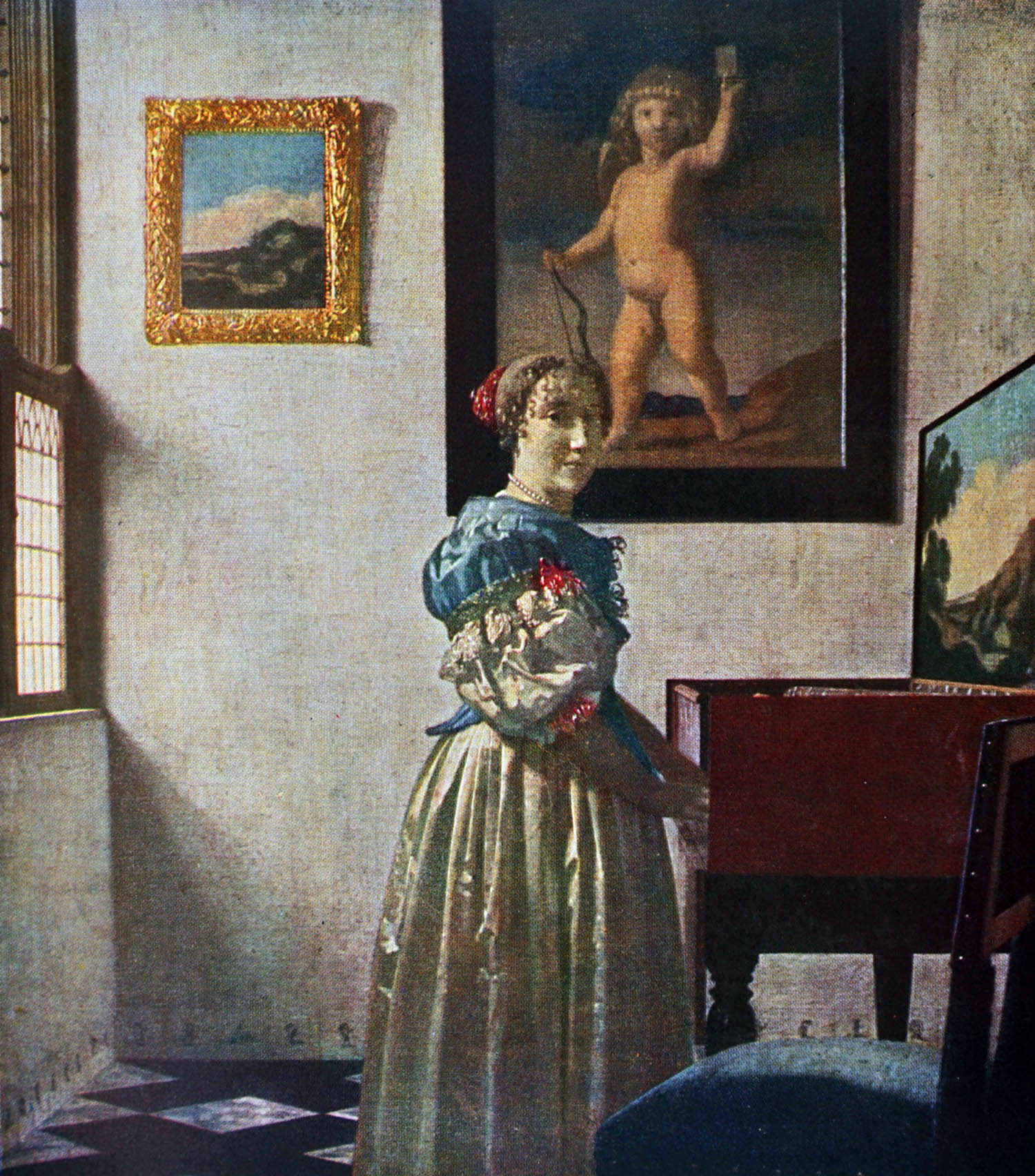

Ever practical Dutch housewives did not want to damage or dirty their white-washed walls when washing the floors, so a strip of tiles was placed as a hard-wearing buffer. Although absorbed by the paintings in Rembrandt’s house, we most admired the Delft tile frieze near the floor. On closer inspection of paintings by Vermeer and de Hooch in the Rijksmuseum, the skirting was there too, miniature paintings within paintings. We vowed to replicate the look at home.

It was on our return I realised we were not the only ones buying tiles like they were going out of fashion. On my Instagram feed, decorators referenced the tiles in historic houses, and trend-chasing Carrie Johnson, wife of a former prime minister, was one of many proud home renovators showing off her new blue and white fireplace.

Hunting for tiles on eBay, while fun, can be a minefield. When you search for them on the site, two categories come up: architectural antiques or decorative collectables, and prices can vary from £28 up to £200 for single tiles that sellers claim are 17th or 18th century. The rule of thumb is that Dutch Delft were more consistent in size than English tiles, at 5.1in square. The side view is important for dating: the thicker the tile the older it is.

Original tiles bought online now decorate the bathroom.

Delftware came about when Europe began imitating expensive Chinese porcelain imports, prized for their pure whiteness. Unable to produce porcelain until the formula and the right clay were discovered in Meissen in 1708, European craftsmen instead added Cornish tin to a white glaze to imitate the Chinese wares. It was known as maiolica in Italy and as faience in France, and it spread to Britain and to the Netherlands, where the town of Delft became known for it.

The golden years of “Delft faience” production were from 1660 to 1720 and its wares were exported across the world. Examples have been spotted as far afield as Rajasthan in India, the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul and in an Ottoman palace in Algiers.

Tin-glazed earthenware with blue or polychrome decoration made in Britain (before and after it was made in Delft) became known as English delftware with a small d.

Matilda Moreton, a ceramicist and painter, who has run delft tile painting courses for many years, attributes the latest craze in part to two 2023 exhibitions: ceramicist Simon Pettet’s work at the house of his partner Dennis Severs in east London, and the Rijksmuseum’s Vermeer blockbuster. Pettet, like the original tile painters depicted things around him, including artists and neighbours Gilbert and George as Tweedledum and Tweedledee. They are mixed in with older Dutch tiles and the juxtaposition of old and new looks very natural and playful.

Lady Standing at a Virginal (1672) by Vermeer features Delft tiles as a skirting board. Universal Images Group/Getty

Moreton first discovered delftware while mudlarking on the Thames, where her favourite finds were shards of pottery featuring its quick, “gestural brushstrokes”. Between the mid-16th and 18th centuries, London boasted about 50 delftware makers on the river’s southeast bank.

The universal appeal of Delft tiles is undoubtedly their hand-painted simplicity and versatility of themes, which make them collectable and timeless. An original Delft tile can feature anything from a seascape, to a Bible story, or just a small leaping dog. There is something for everyone.

Ruth Guilding, author of The Bible of British Taste, says Delftware’s renewed appeal is perhaps due to us “wallowing in nostalgia”. She has seen many examples around the country, and picks out those in the house of antiques dealer Gretchen Andersen, in Sussex. “Her bathtub and sink were surrounded by Delft tiles printed on to sticky backed plastic, made even more realistic because the grouting was black. I couldn’t believe they were not real until I was up close.”

Guilding remembered that Fablon (the brand-that-could-not-be-named by Blue Peter presenters and therefore became known as sticky backed plastic) printed with Delft tiles had been widely available in the 1970s. She asked readers of her website if they would buy a revived version, and cheered by their enthusiasm, set about it. It was then she heard about Not Quite Past, a design start-up that was exploring modern Delft tiles designed by AI.

Jack Marsh and Adam Davies, its founders, have taught an LLM (Large Language Model) to “speak Delft”. Clients enter a prompt, say “bagpiper in front of the pyramids”, and the Delft generator comes up with an image. (Try it, it’s hours of fun). The image is then printed via a transfer to a tile and fired in Stoke-on-Trent.

“Used wisely, AI can bring about a renewed production of objects in the artistic traditions of the past,” explains Davies. I can report that the process feels strangely artisanal.

For our house, we ordered tiles to reflect themes of our family life to sit alongside the older online finds. So now we have a skirting board featuring our lurcher (which baffled US-trained AI but we got there), Istanbul, an F-35, a bagpiper, a Thai temple, a rabbit to commemorate King’s Lynn’s rabbit-infested Hardwick roundabout, and to update the Norfolk windmill, a wind turbine. Whenever I mop my floors, it feels like Delft has come home.

Malika Browne hosts Shows that Go On, a podcast about exhibitions

This week, The Observer has launched a new app and website. Find out more and subscribe here.