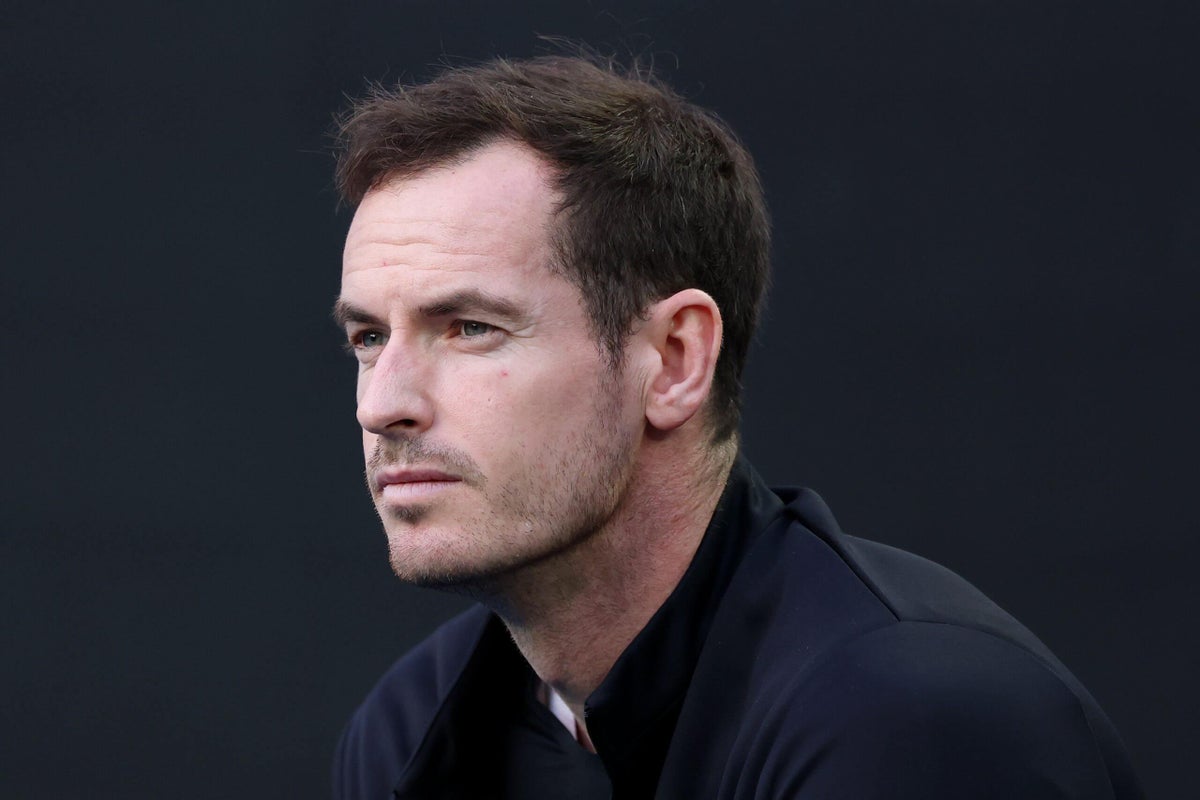

A year on from the start of Andy Murray’s surprise coaching partnership with his longtime tennis rival Novak Djokovic, the three-time Grand Slam champion discussed that partnership, things he would have done differently in his career, and his matchups against Djokovic, Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer in an exclusive interview with The Tennis Podcast.

Murray, 38, also touched on life in retirement. “I was playing Monopoly at 6 a.m. this morning with a six-year-old,” Murray said of his son Teddy when discussing his family life.

Here are the key takeaways from the Scot’s interview, which have been lightly edited for clarity.

On coaching Novak Djokovic

Murray and Djokovic’s partnership ultimately lasted just six months, but produced several highlights, the brightest a fever-dream Australian Open quarterfinal win over Carlos Alcaraz. Murray discussed the huge amount he learned from working with the greatest male player of all time, in even a short stint.

“Novak, like myself, is a challenging character in terms of the way he goes about his … His tennis is extremely demanding. I fully expected that. I look back on it and I’m glad that I did it. You know, it’s an amazing experience that I’ve had.

“It was unfortunate what happened in Australia with the injury, but I watched him play ridiculous tennis in that tournament. Amazing, just so so good, so impressive what he’s doing.

“After the injury, it was certainly a difficult few months for him, but also I think for the team and all of us. So yeah, I was was disappointed. Probably didn’t get the results I would have would have liked for him. But I learned a lot about what coaching is. And because it was throwing yourself in at the deep end, you find out a lot about yourself and some of your strengths, some of your weaknesses as a coach and things that maybe you need to work on.

“I was fully invested. I’d committed to a skiing holiday before I took the job and I explained that to him. But I was sitting there at 11 p.m., watching videos of his matches over in Australia, editing videos to send to him.

“There’s loads of things that you need to do and making sure that everything is done correctly. So making sure that the rackets are right, that the practice court is booked and that the practice partner is appropriate and that the videos around the match are done.

“I viewed that as being my job. It wasn’t like Novak said, ‘Please be the one getting my rackets and stuff.’ I wanted to do those things because you’re then in control of it.

“I think it’s important for a coach to bring a good energy. You don’t want your team to come out and be super flat on an important day, but also nervous energy is not what a player in my opinion needs before they walk on to play the semifinal of a Grand Slam. You need to bring an energy, a bit of confidence as well. So that the player feels like you believe in them. I’m aware from a psychological perspective how important those things are. So it’s something that if I ever coached again, I would work on and try and do a better job of it.

Andy Murray and Novak Djokovic embraced at the end of Djokovic’s titanic win over Carlos Alcaraz at the Australian Open. (Quinn Rooney / Getty Images)

“I felt like it was quite clear as to how he needed to play (against Alcaraz). But there’s a difference between seeing a strategy and actually going out on the court and executing it as well as he did. In my opinion there are very few people in the world that can do that. So you could give a guy ranked No. 50 in the world the best strategy you want to play against Alcaraz, but he is still probably going to win that match.

“Whereas Novak is that good that he is able to execute a strategy perfectly because he is so good. So yeah, I felt like the strategy for the match was a good one, but he played a ridiculous tennis match as well. And that’s why he won the match.”

On his hip injury and what he would have done differently

Murray’s career came to a shuddering halt in 2017 when he was world No. 1, as a hip problem ruled him out for almost a year. He was never the same player again, after an injury that was caused in part by the wear and tear of more than a decade spent trying to keep up with Djokovic, Federer and Nadal. The previous season, Murray had pushed himself to the limit to pip Djokovic to the year-end world No. 1 spot.

It was pushing himself to the maximum and not stopping playing until he’d squeezed out every last drop that gives him contentment in retirement, knowing he left nothing on the table, but he also had things he would have changed.

“I would have taken more breaks. I would have enjoyed the successes more. When I won the Olympic Games (London 2012) I flew the next day to Canada to play the Masters Series there. Terrible decision. I played my first match, my body was in bits, it was on a different surface, I got nothing out of doing that, and actually why didn’t I stay and celebrate what was the best week that I had had on a tennis court? I did the same thing after Rio (the 2016 Olympic Games, when he won the singles gold medal again), I got on a flight that night with Nadal to Cincinnati, and went and played there. Stuff like that I would definitely have done differently.

“I didn’t need to play in Cincinnati, but it was that wanting to compete. I was always drawn to that and sometimes I found it hard to say no to that opportunity.”

Murray also revealed that the hip injury started to bother him a year and a half before the pain got so bad that he had to stop playing.

“End of 2015, my hip was pretty bad and I struggled a lot that year in long matches, in five-set matches. And by the end of those matches I was really struggling, particularly with my serve. It became an issue. And if you look at my results from being two-sets-to-one up in Slams throughout my career up till that point, I rarely lost from that position. And then in those few months, it happened multiple times. I know in myself that physically I couldn’t serve properly and my hip was hurting badly in those longer matches and yeah, it’s possible that if I played less tennis and Cincinnati that my hip would have been feeling slightly better at the U.S. Open, but I don’t think so.

“My hip was already on its way to being finished and I lost multiple matches from two sets to one up, like against (Kei) Nishikori (in the 2016 U.S. Open quarterfinal), (Juan Martín) del Potro at Davis Cup (in September 2016), and (Stan) Wawrinka at the French Open (in the 2017 semifinal). And that was when my hip, eventually it was done.”

On living with the Big Three

“Part of what maybe helped me become more successful, was that I was always striving for more. But at the same time, I spent my whole career getting compared to Federer or Djokovic and Nadal. These are the people that I was competing against and trying to become as good as or better than. So when you’re looking at them and you’re seeing that they’ve won 10, 15, 20 Grand Slams, your achievements when you’re just in the middle of that seem insignificant almost.

“Literally within probably a week to 10 days of retiring, my perspective completely changed on my own career. At times when I was in the middle of it, like No. 3 or No. 4 in the world, and (you’re thinking) it’s rubbish. Or you get to the final of the Australian Open for the fifth time and it’s a terrible result.

“But when I finished my career, and I went and watched my daughter running a cross-country race, and she finished like seventh, and I was like, ‘Oh my god, that’s unbelievable. That’s so good.’ But when I was playing tennis, we finished second in one of the biggest competitions, and you’re like, ‘This is just a disaster.’ It’s not an ideal way to look at things. It’s hard to get much happiness and pleasure out of the sport when that is the mindset. I think a lot of athletes suffer from it.

“I’m fully aware, like where I sit in the pecking order, I know that what all of those guys have gone on to achieve is far superior to anything that I did on the tennis court. But also there was a period like in the middle part of my career where most major events, whether that was the Slams, Masters Series, Olympics, Davis Cup, that one of those four players was winning. Now granted most of the time it was them, but it wasn’t always. And yeah, I was proud to have been part of that period.”

Andy Murray with Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic at Nadal’s retirement ceremony in Paris earlier this year. (Li Jing / Xinhua via Getty Images)

Murray then discussed what it was like playing the Big Three, starting with Federer, who he beat in six of their first eight matches before ending his career with a 14-11 losing record against the Swiss.

“His backhand would still have been one of the best backhands in the world, but in relation to his forehand, it was clear that that was a side that you could maybe attack and my backhand crosscourt was one of my best shots. I also used to like playing this sort of high forehand, down the line, that was sort of slow. I’ve never asked him about it, but I didn’t always hit it super deep. It was high, but short in the box, and for a one-hander it’s difficult. You need to make a decision early, to step into the court and try and take it early, or retreat and go back behind the baseline.

“I felt like that shot gave him some trouble, particularly early on when we played. Obviously he figured that out the more I played against him.

“Over the years he got progressively more offensive, particularly with his court position, and my second serve was average at best. And as I played against him more, he was more offensive on second-serve return, trying to get on his forehand more when I was hitting second serves. Whereas at the beginning, he would often sort of stand on the baseline, and if I served to his backhand would just chip it back and start the rally.

“Rafa served differently on grass than how he did on a clay court. He served faster, tried to serve more aces, tried to get more free points on his first serve. And then on the second serve I felt like he also upped his speed at times on the grass court and because of the nature of the surface, his second serve became a little bit harder to return and he would serve quite a lot to me on a grass court into my forehand body. It would sort of slide through and come into my body and I found returning against him significantly harder on a grass court than on the clay. And then his forehand was great on every surface.

“He had very solid volleys, good hands. He was quick at the net, anticipates well at the net and he was able to use those skills more on a grass court than maybe he did on the clay.

“Novak was a difficult match for me because we have very similar game styles, but everything (he did) was just a little bit better. The only area where I was probably stronger was at the net. But then it’s hard to sort of exploit. It’s not like he’s not good at the net. He’s not like a terrible net player, and how do you make that work to your advantage? If I want to bring him up to the net, it’s not an easy thing to do. You can at times, but you can’t spend every point hitting drop shots or hitting short balls to try and get him to come forward. So it wasn’t really that easy for me.

“One of the things where there was a big difference is when I would hit a slice backhand to Novak, most of the time he would come back with a slice. His slice is sort of quite slow, whereas someone like Federer really knifes his slice. It was a strength of his. Novak wouldn’t miss many, but it was a slower ball. And when I got on my forehand after that shot, so when he sliced and I was the one to get my forehand, the percentage of points that I won was significantly higher. So that was something towards the end when I played against him that I focused on a lot. So then I would bring the slice into the rally immediately trying to get on my forehand as much as possible. And that seemed to help a bit against him.”

On the tennis schedule and player burnout

Murray opposed increasing the number of two-week ATP Masters 1000 events (the rung below the Grand Slams and such a hot topic this year) two years ago. Like many he emphasised that it’s not the greater volume of tennis that’s the issue necessarily, but the increased time on the road and the mental load that puts on players.

“I was sitting on the ATP player council when this got voted for, to change to longer events and I was completely against that change … The feeling from the ATP at the time was there would be less injuries, because you would have more time to recover between matches. My feeling was that if you put two-week tournaments on there’s less time for players to actually recover. I don’t think there’s anything that suggests players are getting more injured before … But I do think players are more tired, and I think mentally more fatigued than they were before because they’re spending more days away and more days on the road and when you’re more fatigued, you’re more sensitive to pain and discomfort.

“The matches, I don’t think they’re so much more demanding than they were 10, 15 years ago. But it’s the amount of time that players are away on the road that’s actually an issue.”

On life in retirement

“I don’t cook. I’m a terrible cook. I used to cook more. There’s a recipe that you follow [in a meal kit] but the problem for me is that I will follow the instruction down to a T, and so if something isn’t going quite right, I have no idea how to make adjustments … I retired from cooking as well as tennis.

“I was still playing at the end, but there were quite a few periods when I was at home through the injuries, I wasn’t playing quite as much. For my eldest daughter, it was quite a big change for her, quite a big adjustment. She was finding it hard if I had to be the one to take her to school, or to pick her up, take her to a club or being around her friends, that was something she was finding difficult. If I was getting any attention she struggled with that.

“It was only last week when I picked her up from netball, it was the first time that she actually walked next to me back to the car.