European governments that condemn Israel and announce sanctions still line up for its air defense systems, as fears of Russian drones and other threats override political boycotts

Germany is pressing Israel over West Bank annexation and Palestinian statehood even as it proceeds with multibillion-dollar defense deals and resumes approving weapons exports to the country, underscoring how security cooperation is being maintained despite deep political disagreements.

At a joint appearance in Jerusalem, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz warned against any steps in the West Bank that might amount to annexation, insisting there should be “no formal, political or structural measures” in that direction and reiterating that “recognition of a Palestinian state should come at the end—not the beginning” of peace negotiations.

Netanyahu, who greeted Merz as a “friend,” focused almost entirely on security. He again rejected Palestinian statehood, asserting that “the purpose of a Palestinian state is to destroy the one and only Jewish state,” and vowed that Israel would maintain security control “from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea.” He said the first phase of President Donald Trump’s 20-point ceasefire plan for Gaza was nearing completion and that he would meet the American president later this month to discuss the second phase, which centers on Hamas’s disarmament and Gaza’s demilitarization.

The disagreements did not end there. Merz expressed concern about Israel’s conduct in Gaza and about the International Criminal Court’s arrest warrant for Netanyahu, while the prime minister denounced the charges as politically motivated and made clear he has no intention of stepping aside, saying that “they are concerned with my future. Well, so are the voters, and they will decide.”

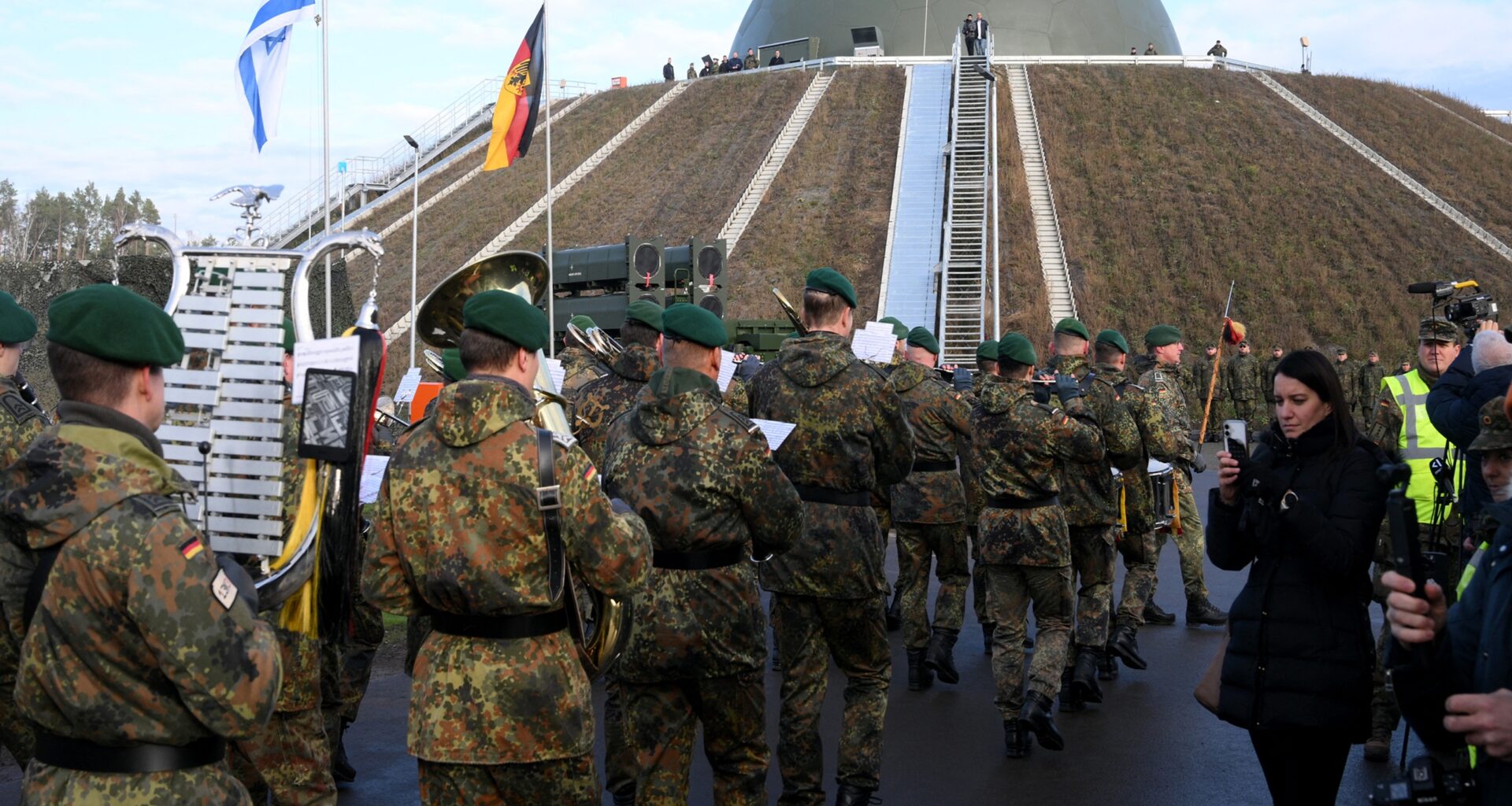

Yet even as the two leaders clashed in public over the future of the West Bank and Gaza, both underlined that security cooperation continues. Germany remains Israel’s second-largest arms supplier after the United States and has resumed approving weapons exports after a partial freeze linked to Israeli operations in Gaza. At the same time, Berlin is now a major customer of Israeli systems: Merz’s arrival came just days after Israel handed over its Arrow 3 missile defense system to Germany in a landmark transfer widely described as the largest single arms export deal in Israel’s history, worth roughly $4.5 billion.

Merz’s visit to Israel over the weekend captured the uneasy mix of friction and reliance that now defines ties between Israel and one of its most important European partners.

“The German embargo was not easy for Israel,” Dr. Yehoshua Kalisky, a senior researcher at the Institute for National Security Studies, told The Media Line. “Germany is Israel’s second weapons supplier after the US.”

Last month, as the ceasefire in Gaza appeared to hold, Germany announced it would be partially lifting the embargo. Speaking alongside Israeli President Isaac Herzog on Saturday, Merz explained Germany’s stance.

“The actions of the military and government put us in a dilemma,” he said. “We had to respond, but rest assured we are still by your side.”

Germany is far from alone in trying to balance political pressure with strategic dependence on Israel. A string of European countries, from Spain and the United Kingdom to France, the Netherlands, and Belgium, as well as Canada, announced an arms embargo on Israel during the war. Germany barred Israel from buying tank shells from it, and the United Kingdom also announced the suspension of some of its weapons sales to Israel. Similar sanctions came from France, Canada, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Spain.

As one of Israel’s most vocal critics, Spain cancelled large contracts it had with Israel at the beginning of the war, amounting to millions of Euros in lost revenue. Other countries that have announced embargoes still continue to purchase systems and technologies from Israel.

There is a lot of fear in Europe from Russian drones and other weapons. Israel excels at air defense systems.

“There is a lot of hypocrisy,” said Kalisky. “There is a lot of fear in Europe from Russian drones and other weapons. Israel excels at air defense systems, so countries can boycott Israel in many arenas, but when it comes to their defense, they will purchase exactly what they need and want from Israel.”

Several media reports claim Spain is still purchasing minor components from Israel, even under the embargo, flagging them in the national budget as “strategic programs” without mentioning the source.

Kalisky also mentioned Finland as an example of Israel’s complex standing. Finnish President Alexander Stubb condemned Israel for violating international law during the war. Yet, it proceeded with major purchases from Israeli defense firms, including the purchase of the David’s Sling medium-to-long-range surface-to-air defense system designed by Rafael.

There is no substitute for Israel’s operational experience and sophisticated systems

“All European countries buy from Israel in one way or another, because there is no substitute for Israel’s operational experience and sophisticated systems,” he explained.

In the aftermath of a lengthy war that placed Israel in international isolation and under intense global pressure, the country’s defense industry exports have excelled, cementing its position as a world leader in the arena.

According to the Israeli Defense Ministry, 2024 was the fourth consecutive year in which export levels broke the previous year’s record. Israeli firms sold almost $15 billion worth of weapons systems around the world, with European countries taking the lead.

“War is the best sales promotion,” said Kalisky. “Wars have a huge impact on the defense industry, both directly and indirectly.”

War is the best sales promotion

Dr. Uzi Rubin, a former founder and director of the Arrow project at the Defense Ministry and an expert on missile defense systems, cites the war between Russia and Ukraine as a turning point for the global arms industry, adding that tensions between China and Taiwan have also impacted the market.

“The war and the tensions increased the demand for weapons systems, and the demand for such systems is immediate,” Rubin, an aeronautic engineer, told The Media Line.

“Countries carefully watched the performance of the F-35 and F-16 fighter jets, and this was good for American companies like Lockheed Martin, for example,” Kalisky added.

The American firm was ranked first in the 2024 Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) ranking of arms-producing and military services companies in the world. Israeli companies Elbit Systems, Israel Aerospace Industries and Rafael were ranked 27, 31 and 34, respectively—all displaying a double-digit increase in their revenues. A compact but influential player, Israel’s position in the global market is solid.

The data on Israeli firms could come as a surprise, as criticism of Israel’s conduct during the war, which included accusations of genocide and war crimes, was translated by some countries into actual sanctions against Israel.

As the Middle East war appears to have concluded, other wars in the world are still ongoing, making the demand for weapons constant. Israeli industries are just one of the few to benefit, with a marked advantage of vast hands-on experience.

“Israel has another two advantages—it supplies the product very quickly and is also willing to engage in joint projects with its clients, thus sharing its knowledge,” Rubin explained.

Last week’s ceremony at Holzdorf Air Base south of Berlin, in which the Arrow missile defense was handed over, came two years after the signing of the deal—an uncharacteristic speedy delivery in the defense world.

According to SIPRI, the global demand for weapons has pushed the arms industry to record levels, making it an industry that made almost 700 billion US dollars in revenue in 2024 alone.

India is a rising star in the field, making a deliberate pivot from importer to producer and exporter under the “Make in India” flagship program, which is aimed at turning India from a major importer of weapons into a global arms manufacturer by boosting domestic production, cutting reliance on foreign suppliers, and increasing defense exports. This has resulted in a sharp climb in exports with Indian-made guns, helicopters, drones, and other components being used by armed forces around the world.

“India is making a lot of headway, focusing on very sophisticated offensive technologies, making it a superpower,” said Kalisky. “It relies on Israeli technologies for much of its defense.”

The SIPRI report also marked 2025 is a pivotal year for Middle Eastern firms from Turkey and the United Arab Emirates. It is the first time nine Middle Eastern companies made the global top-100 arms producers list, collectively earning some $31 billion in arms revenues, thus increasing regional export capacity. This could potentially reduce these countries’ dependence on Western suppliers, but more importantly, it could shift the balance of power in the region in favor of those states that produce rather than just acquire weapons.

“Turkey has invested tremendously in its defense industries, making it a threat to Israeli industries,” said Rubin. “Buying from Israel always comes attached with political considerations, an advantage that Turkey has over Israel—it faces no embargoes.”

According to Rubin, Saudi Arabia is also on its way to becoming a major player in the industry. It has shifted at least a quarter of its defense expenditure to domestic production—focusing on drones, electronic warfare systems and armored vehicles. Saudi firms are making a reputation as credible weapons suppliers. This would mark another significant regional shift that could reposition Riyadh from a substantial regional buyer into a key arms exporter.

All of these changes could recalibrate geopolitical balances across the Middle East.

When considering defense contracts, there has often been concern in Israel that its knowledge will land in the wrong hands, especially those of its sworn enemies.

“There is no good response to this; it is definitely a risk,” said Rubin. “Israel tries to make sure the knowledge that leaks is not critical knowledge, but this cannot be completely avoided.”

Israel has grappled with this risk before: past disputes over drone upgrades for China and concerns about reverse-engineering of captured Israeli systems—including by arch-rival Iran—have demonstrated how sensitive technology can spread despite putting as many safeguards in place as possible. Officials often point to these episodes as proof that once advanced weapons enter foreign supply chains or conflict zones, some degree of knowledge leakage is almost impossible to prevent.

Facing the diplomatic fallout of the war and growing competition from emerging producers in Asia and the Middle East, Israel’s defense sector remains firmly placed among the world’s leading suppliers—sustained by updated battlefield-tested systems, rapid delivery capabilities, and a global market hungry for reliable, tried-and-tested technology. But as new powers rise and geopolitical alignments shift, Israel’s defense industry will need to keep itself on its toes to navigate an increasingly crowded arena in a constantly changing, complex political landscape.