Inside a heaving A&E where tempers flare, lights flicker and patients wait four hours just to be seen, the only thing stopping the chaos from tipping over is the relentless kindness of staff stretched far beyond their limits says James Holt. Is this the A&E we have come to accept?(Image: Manchester Evening News)

Is this the A&E we have come to accept?(Image: Manchester Evening News)

“No tea and no f***ing coffee,” a man grumbles. He is sat opposite with his carer and has been for a number of hours, getting increasingly frustrated and restless. He’s fidgeting with the remains of a sad-looking wrap in its packaging. He wants a hot drink – but there’s nowhere to get one.

A teenage girl is rowing and fighting with her boyfriend and being told to calm down by security.

Another is on the phone to someone threatening to ‘punch their head in’. One of the fluorescent lights is flickering above us. Paint is peeling off the walls.

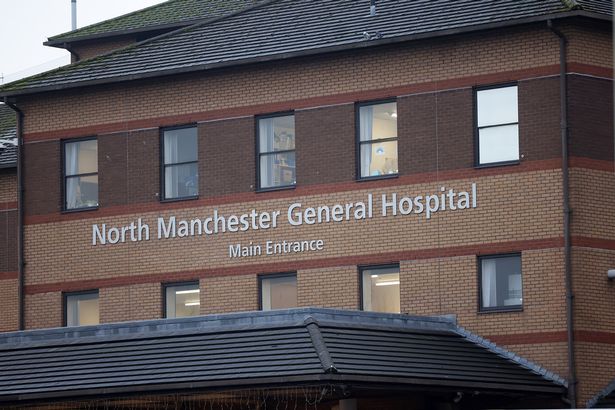

This is the waiting room at North Manchester General Hospital. To get here, we have walked through a packed A&E seating area, filled to the brim with poorly people and the chaos of staff rushed off their feet and working themselves to the bone.

There are waits of over four hours to be seen after triage. It’s unbearably hot. The front reception desk has a queue of people waiting. Others are slouched in wheelchairs in the corridor or slumped, visibly defeated, against the wall.

Except this isn’t a busy Saturday night in one of the UK’s busiest cities – it’s 9pm on a Tuesday.

My partner had been urged to visit the hospital by call handlers at 111 however was told a wait for an ambulance would be over four hours. Living nearby, we opted to drive with hopes of being seen sooner, but knew we were likely in for a long night.

We spent four and a half hours at North Manchester General’s A&E(Image: Men Media)

We spent four and a half hours at North Manchester General’s A&E(Image: Men Media)

It’s a place where people go to be cared for and looked after when they need it most. But the experience felt somewhat apocalyptic, unpleasant and unsafe. Were A&E departments always this hectic, uncomfortable and surrounded by around-the-clock security?

After finding two seats in the packed waiting room, next to a stained wall support with paint peeling off, it was only around 15 minutes for him to be triaged. Then we were moved out of there and into the Urgent Care treatment room next door, which was similarly busy.

Over the course of the next few hours, fed-up patients repeatedly asked the triage nurse on reception, who continued with kindness in her eyes and a forced smile through it all, how long the wait would be.

It was three-and-a-half hours, then four, then four-and-a-half.

“It’s really busy, and there’s only one doctor. I don’t know how long it will be,” she uttered to a chorus of disappointed sighs.

The man sat opposite us wanted a hot drink, but the coffee machine was out of order. A greasy handwritten sign told us so. The café and restaurant had both shut up shop. One nurse was kind enough to make him a brew – with four sugars – in his flask from the staff room.

The two vending machines in the block were virtually empty, and kept flashing error warning signs for ‘no stock’ – despite the digits we had selected being some of the few shelves that were actually full. The water machine in the unit had no plastic cups on top of it so there wasn’t anywhere to get a drink.

The hospital in north Manchester (Image: Manchester Evening News)

The hospital in north Manchester (Image: Manchester Evening News)

The staff told patients and their loved ones that the only way to eat would be to ‘order an UberEats’. The smell of greasy takeaway food and McDonalds lingered in the stuffy air.

The whiteboard across from us, with a laminated ‘waiting times’ poster on it, hadn’t been filled out. There were virtually no updates as the evening drew slowly on, meaning nobody really knew how long they’d be waiting or where in the priority line they were to be seen.

Booming tannoy messages kept calling for doctors and nurses to rush to other departments for bigger emergencies. The bathroom hand dryer had broken and there were no paper towels left to dry our hands.

They may only be small annoyances in isolation, but together, paired with the waits and overall experience, do nothing to make poorly patients feel any more comfortable or secure.

But we weren’t the only ones. This is happening everywhere. Our experience came on the same night that other trusts in the region warned of ‘extremely busy’ waits in A&E and reports of over 50 hours for a bed elsewhere.

With each nip outside for fresh air came the same dreary walk past the ever bulging room of patients, all still waiting. I saw the same faces over and over. Time felt like it had stood still.

The A&E department was exceptionally busy(Image: Manchester Evening News)

The A&E department was exceptionally busy(Image: Manchester Evening News)

But looking around, it was the staff who are undoubtedly the beating heart of the place. They keep it all going – no matter what. They are the shining beacon of light in our national health service.

Nobody was talking about their ailments in the waiting room or wailing out in pain, but rather discussing the chaos of the department or consoling one another with reassurance that they will, eventually, at some point, be seen.

One woman was in a wheelchair in the hallway attached to a drip. Another man had his leg in a cast and had it propped up on two of the seats. Others decided they’d had enough and went home. It felt undignified and, to be frank, quite degrading.

But the nurses, in their blue scrubs, kept in good spirits. Every query was met with a warm smile. Each patient, my partner included, must have felt respected and heard. Staff, who were too often the brunt of verbal attacks and complaints, are merely at the mercy of workplace pressures.

They carry the weight of the NHS on their shoulders, and do the service proud. Wait times are high because the line at the door keeps growing. Chronic underfunding leaves them in limbo. But with every sigh of frustration, they simply cracked on. It isn’t just treating patients, it’s keeping everything running, being pulled from pillar to post, without so much as a flinch.

After four hours and 30 minutes, my partner was seen. His assessment took around 20 minutes, he was told about the appropriate care needed and we were sent on our way, arriving back home shortly before 3am.

It was clear from our experience that the annual A&E winter crisis has gripped a firm hold once again, and will be adding to the already existing pressures. But it’s evident it’s much more than just that.

There were patients pushed together from all walks of life and with a myriad of health problems that all needed seeing to. Some clear, some invisible, its a mix of people with urgent conditions or others who couldn’t get an appointment with a GP.

And as we finally stepped back out into the cold early-morning air, it struck me that nothing about the night had felt shocking. Not anymore.

The overcrowding, the silence between strangers, the apologetic smiles from staff who have nothing left to give but their patience. This is simply what we all expect now. That might be the most worrying diagnosis of all: not the crisis itself, but how quickly we’ve learned to live with it.