Until recently, the Albanese administration had been tentative in its dealings with President Trump, but will likely find common ground moving forward.

Prime Minister of Australia Anthony Albanese (left) and U.S. President Donald Trump (right) shake hands after signing an $8.5 billion rare-earth minerals agreement during a bilateral meeting at the White House on Oct. 20. © Getty Images

Prime Minister of Australia Anthony Albanese (left) and U.S. President Donald Trump (right) shake hands after signing an $8.5 billion rare-earth minerals agreement during a bilateral meeting at the White House on Oct. 20. © Getty Images

×In a nutshell

- Relations between the U.S. and Australia have been shrouded in uncertainty

- The Pentagon’s recent review of AUKUS rattled the Australians

- Most signs suggest that the strong relationship will continue – with tweaks

- For comprehensive insights, tune into our AI-powered podcast here

On October 20, United States President Donald Trump and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese met in person. Mr. Albanese was one of the last major allies in the Indo-Pacific to have a face-to-face meeting with Mr. Trump. Given that many expected the Trump administration to make a dramatic “pivot to Asia,” the relationship between the U.S. and the Australian Labor government was anticipated to be a top American priority.

The meeting in Washington D.C., where the pair signed a rare-earths deal, was a positive signal, but the government in Canberra remains tentative, with no clear strategy on how to handle its relations with the U.S., and seemingly no understanding of what Washington expects from one its most consistent and unflinching allies. Indeed, few countries are less certain about how to engage with the Trump administration than Australia.

America needs Down Under to counter China

The fundamental value of Australia as an Indo-Pacific ally of the U.S. is as important as ever. Australia’s geostrategic relevance to the U.S. is on par with its importance in 1942, when it was the key strategic platform empowering the American effort to counter the First Island Chain. Australia provided the U.S. with unprecedented access to the Asian continent, enabling allied powers to bridge across Europe and the Middle East through the Indian ocean to Asia.

Today, Australia plays an equally critical role in allowing the U.S. and its allies to counter China’s play for regional dominance and global influence. The country is invaluable when it comes to engaging with strategic Pacific Island nations to prevent Chinese efforts to secure a military base that could serve as power-projection platform in the First Island Chain.

×Facts & figures

Australia’s geostrategic position

The First Island Chain is a term used by the U.S. to describe the string of islands stretching from Japan, through Taiwan and the Philippines, to the Malay Peninsula. This chain forms a strategic military barrier designed to contain China’s military expansion into the Pacific Ocean. Australia’s defense capabilities are critical for regional stability south of the chain. © GIS

The First Island Chain is a term used by the U.S. to describe the string of islands stretching from Japan, through Taiwan and the Philippines, to the Malay Peninsula. This chain forms a strategic military barrier designed to contain China’s military expansion into the Pacific Ocean. Australia’s defense capabilities are critical for regional stability south of the chain. © GIS

Aside from geography, Australia matters to the U.S. because it is one of the world’s most important mining powers for a range of ores, including critical minerals and rare earths. It is also a valued defense and technology partner, in industry and in space, providing the largest number of NASA tracking stations outside the U.S. Finally, Australia is an important intelligence partner, detecting strategic early warnings and providing important cooperation for protecting U.S. interests in the Antarctic region.

×Facts & figures

The U.S.-Australia rare-earths deal

- Signed in Washington, D.C., on October 20.

- Supports $8.5 billion worth of mining and processing projects in Australia.

- China currently controls about 70% of global rare-earths mining and 90% of the processing capabilities.

- The U.S. sources 80% of its rare-earth imports from China, while the European Union relies on China for about 98% of its supply.

- Other than China, Australia is one of the few countries in the world that processes rare earths.

- This deal is intended to boost its processing capacities and provide an alternative source of minerals for the U.S. and allies.

Distant allies

While many expected the U.S. administration to focus primarily on the Indo-Pacific, President Trump currently has America’s military, economic and diplomatic power focused on dealing with wars in Europe and the Middle East. He is also prioritizing ramping up engagement in Africa, the South Caucasus and Central Asia, while solidifying U.S. influence in the Western Hemisphere. At the same time, he is personally engaged in negotiating trade and other economic deals with China, including a squabble over ownership of the U.S. platform of TikTok.

Meanwhile, the U.S.’s combative relationship with India, one of its most important regional security partners, has sent mixed signals on the U.S.-Taiwan relationship. In contrast, relationships with both Japan and South Korea, which recently agreed to trade deals, seem stable. The president’s focus on these relationships has left Australia feeling starved for attention.

The current Labor-led government has a weak and indecisive foreign and defense policy. At least publicly, the government appears much more tentative about the China threat than is warranted given China’s aggressive and sustained effort to establish regional dominance. The Albanese administration remains averse to antagonizing China despite national assessments repeatedly concluding the Chinese are actively attempting to encroach on Australian vital interests.

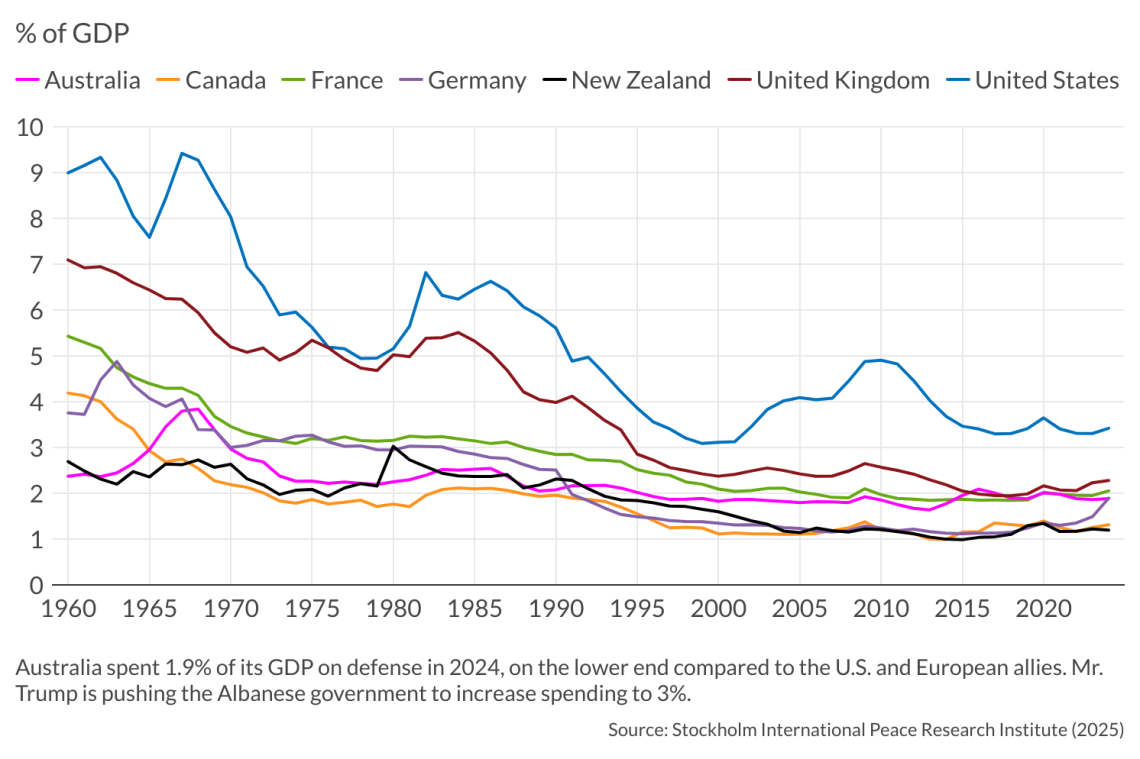

The government’s current plan of spending 2 percent of gross domestic product on defense is widely considered barely adequate to meet national defense requirements and materially contribute to regional security. Unlike Europeans, who have preemptively and, in some cases proactively, responded to President Trump’s demands that allies deliver more for collective security, the Australian government appears reluctant to initiate proposals to increase defense spending and responds negatively to pressure from Washington to do so.

×Facts & figures

Military spending as share of GDP

Defense priorities

Amid allied insecurity, the U.S. Department of War announced a review of AUKUS – a major joint defense partnership between Australia, the United Kingdom and the U.S. The Australian government is deeply concerned about the U.S. review of the program, which it sees as its most significant future commitment to conventional deterrence in the region. Under current defense projections, Australia will have difficulty sustaining AUKUS and other critical defense needs, but without AUKUS it loses significant strategic weight.

The three to five Virginia-class submarines the U.S. has promised to deliver to Australia in 2035 seems like a reasonable trade for cementing a deep-strategic regional partnership. It is in U.S. interests that the review focuses on ways to accelerate and strengthen the program. During the recent meeting between the two leaders, Mr. Trump responded to the question of whether Australia would be receiving the subs, saying, “Oh no, they’re getting them.” This surely came as a relief to Prime Minister Albanese, as the lack of reassurance from Washington had been stirring misgivings and causing concerns in Canberra.

Both the ruling Labor Party and the main opposition, the conservative Liberal Party, have made AUKUS the cornerstone of the national defense plan. They are committed to AUKUS, and have no Plan B if it collapses. The program clearly has some management problems. The federal government and the state government of Western Australia, which hosts most of the industrial base and the submarine facilities, do not seem on the same page in terms of the commitment and investment to aggressively expand the partnership.

Despite these issues, it is now clear that while the review may include some planning and efficiency tweaks from Washington, the program will nonetheless continue to move forward. A senior Pentagon official involved in the review stated on November 6, “It is in our interests for this to work – we gain significant benefit from it, so we want to make it as strong as possible.” That assurance alone adds great stability to the bilateral partnership. The review is scheduled to be completed in the first half of December.

AUKUS summit on March 13, 2023, in San Diego, California. Former U.S. President Joe Biden hosted then British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese to discuss the procurement of nuclear-powered submarines under a pact between the three nations. The future of the deal has been less certain under President Trump. © Getty Images

AUKUS summit on March 13, 2023, in San Diego, California. Former U.S. President Joe Biden hosted then British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese to discuss the procurement of nuclear-powered submarines under a pact between the three nations. The future of the deal has been less certain under President Trump. © Getty Images

Uncertainty from U.S. clouds Australia-Taiwan relations

Few issues perplex the Australians more in their bilateral security relations with the U.S. than their role in a Taiwan contingency. There remains lack of clarity over the U.S. strategic intent, and of what the U.S. expects from Australia on this issue. There are significant concerns over the declaratory policy, the U.S. official stance of ambiguity on whether it would or would not intervene military if China were to attack Taiwan. It is also unclear how, if Australia were to overtly support and engage with Taiwan, this would impact its relations with China and with the U.S. Since there is no consensus in Canberra on Taiwan, the uncertainty from Washington is deeply problematic for Australia.

Canberra is not pressing its IMEC advantage

Canberra has so far paid little attention to the importance of the India-Middle East-Europe Corridor (IMEC), underrecognizing its relevance to Australia as well as to the U.S. and other allies. One key strategic node in IMEC is the passage through the Middle East and Israel, but the other is the passage through the waters from the Indian to the Pacific Ocean. This eastern node is anchored on one end by India and on the other by Australia. The gateway is a crucial bridge in linking the Indo-Pacific with the Indo-Mediterranean, and it has significant strategic implications for Australia.

Yet, Australia (and, for that matter, India) are not being proactive in pushing joint strategic initiatives with the U.S. There has been some progress under the Quad, and more Australia-India cooperation, such as the joint naval maneuvers of Exercise Malabar. However, deep collaboration, integrated strategic thinking and proposed action from the two countries are lacking. The U.S. would regard such steps as a meaningful commitment to securing the eastern maritime gateway to IMEC. Australia is also underemphasizing its major advantage: its core strategic role in the Indian Ocean.

Contrasting visions on China

A key factor exacerbating the challenges in the relationship is that it is clear that U.S. and Australia have completely opposite visions for achieving conventional deterrence against China. Canberra’s focus is on building a long-term deterrence architecture including political and diplomatic partnering, establishing regional norms and gradually closing defense capability gaps. The U.S. takes seriously the assessment of China’s intent to have formidable and decisive power-projection capability to move on Taiwan by 2027. In light of this, the U.S. focus is ramping up conventional deterrence posture as quickly and robustly as possible.

Without a clear understanding of the U.S.’s direction or confidence in how to engage, the Australian policy seemed to be: wait and see. On the one hand, there are cautionary voices such as Professor Hugh White, who in his essay “Hard New World: Our Post-American Future,” forcefully argues that the U.S. is no longer a dependable ally for Australia. On the other, there is a level of complacency; a belief that Australia is an invaluable strategic asset for the U.S. and all Canberra has to do is the bare minimum to keep America happy.

In the middle of this continuum lay the frustrated, who think whatever the U.S. strategy, working with key regional allies is invaluable to achieving deterrence against increasingly malicious Chinese actions in the near term. This group holds that Australia’s contributions to these defense partnerships are vital – and currently inadequate.

By proposing this strategic rare-earths deal with the U.S., the Australian government has signaled its intent to adopt such a middle ground, implementing additional measures to strengthen the bilateral relationship.

Angst over Israel

The Australian government’s recent decision to recognize Palestine, following the lead of France, the United Kingdom and Canada, is highly controversial. The recognition of Palestine has long been part of the Labor Party platform, but it complicates constructive engagement between the U.S. and Australia. The move has received an ambivalent response at home, and has delivered little domestic political advantage.

×

Scenarios

Somewhat likely: Australia ramps up its efforts to deepen U.S. relations

There are many initiatives Australia could take to broaden its U.S. relationship beyond the AUKUS framework. It could, for example, further develop its maritime situational awareness and regional sea-control. It could expand basing, logistics, power-projection and deep-strike capabilities for U.S. and allied forces. It could step up cooperation on combating illegal fishing, as well as drug and human trafficking. It could be more proactive in establishing a role in IMEC and bolstering its joint partnership with India. Finally, it could engage in more long-term and deliberate joint efforts to secure joint U.S.-Australia interests against China in the Antarctic region.

The rare-earths deal signed between the two countries last month is a positive signal that Mr. Albanese and Mr. Trump may be able to work well together. Yet, given the weaknesses in the AUKUS program that the U.S. wants Australia to address, this may be Canberra’s priority, resulting in it leaving the other initiatives aside.

Most likely: Continuity grounded in AUKUS

Backing initiatives such as those mentioned above seems like too daunting an agenda for the present government. The more likely scenario is continuity of the status quo. Given that AUKUS represents the flagship of Australian foreign and security policy, the Pentagon’s review of the program rattled the Australians and raised serious doubts about the continued partnership. However, as the review draws to a close, the signaling from the U.S. is that AUKUS will move forward with American support and the U.S. alliance will remain foundational to Australia’s security posture.

Australian-U.S. relations will therefore likely teeter along, relying on a combination of American security and deep economic engagement with China. Canberra will continue to counter incidents as they arise in Beijing’s continued efforts to expand its footprint in the theater, particularly as it tries to secure a “military-capable” port.

Contact us today for tailored geopolitical insights and industry-specific advisory services.

Sign up for our newsletter

Receive insights from our experts every week in your inbox.