We Think (Omnisis), Survation, Techne UK, Opinium, Deltapoll, More in Common, YouGov, Ipsos

(Bloomberg) — It’s true the most dismal predictions about Brexit didn’t come true — immediately.

But while there was no mass exodus of firms from London and the recession the Bank of England warned of never transpired, a slew of economists are using fresh calculations to assert the damage has been far worse than previously believed.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Their conclusions come at a time when the governing Labour Party is gingerly approaching a subject that was for so long taboo because its voter base straddles both sides of the contentious divide. Labour’s new strategy of fronting up against the insurgent party led by Brexit’s biggest cheerleader, Nigel Farage, is giving them courage to do it. And new findings on the long-term costs of Brexit might just strengthen their resolve.

Far from being too pessimistic, the UK’s official forecaster underestimated a predicted 4% dent to the UK’s long-term gross-domestic-product by as much as half, implying a more-than £200 billion ($267 billion) cost to the economy, according to a new National Bureau of Economic Research paper authored by economists including Nicholas Bloom, Philip Bunn and Paul Mizen.

Photographer: Jose Sarmento Matos/Bloomberg

Another by the Centre for European Reform’s John Springford reports a similar finding: that without Brexit the UK would have registered growth rates closer to the US than France and Germany.

Forecasters were actually “really accurate,” said Mizen, professor of economics at King’s College, London. “It’s just that they thought that it was going to happen earlier.”

Last week Prime Minister Keir Starmer said his country “must confront the reality that the botched Brexit deal significantly hurt our economy,” echoing a wider shift in tone. His Chancellor Rachel Reeves spent the prelude to her November budget blaming it for low productivity, prompting another prominent member of the cabinet, Wes Streeting, to say he was glad to finally be able to admit Brexit is a “problem.”

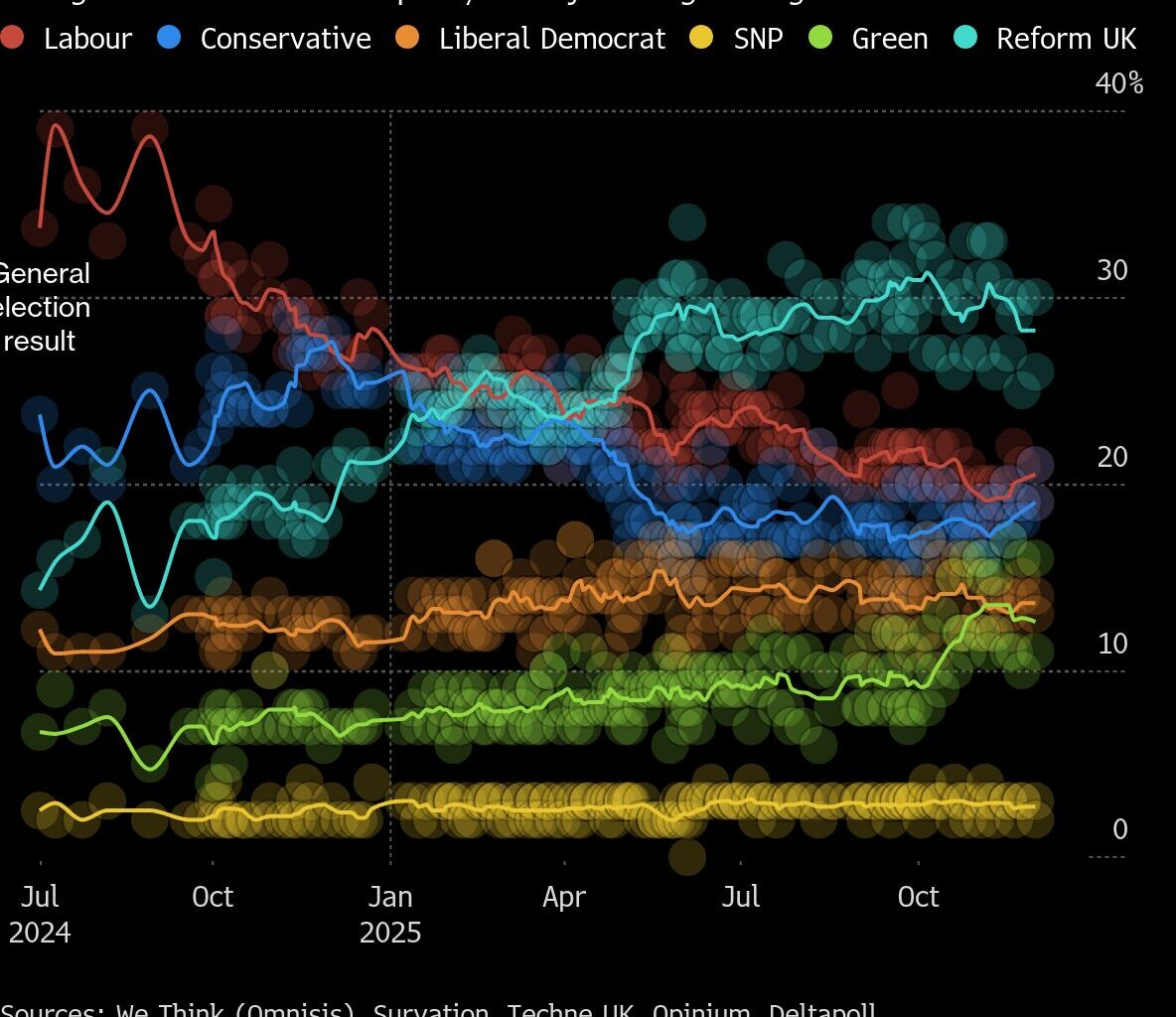

The government’s approach toward the European Union still, from the outside, looks ambivalent. It has long been wary of re-litigating the fight in case it pushes working-class voters toward Farage’s Reform, in the lead in national polling since April. But in October, Bloomberg reported that officials believe steps to closer alignment could deliver meaningful benefits ahead of the next election.

Story Continues

They’re also looking to shore up Labour’s vote in the face of threats from the left and center, where the Liberal Democrats have long argued for unambiguously closer ties.

The pro-EU party wants to force Labour MPs to declare their affiliations overtly — or suffer the political consequences of demurral — in a vote they’ve called for Tuesday asking the government to negotiate a new customs union. They’ve written to Labour members of parliament about it citing the NBER research, the Guardian reported.

That research suggests muddled messaging is itself to blame for negative impacts. Mizen says “Brexit was not a one-off shock,” but a series of events that prolonged uncertainty for businesses in ways that are still playing out. His paper argues the economy was hurt by uncertainty that crimped investment, encouraged firms to pull back on spending and hiring, and created opportunity cost as firms spent years sidetracked preparing for new trade rules rather than concentrating efforts on innovation.

The NBER hypothesized a counter-factual, no-Brexit UK constructed from a basket of economies that registered similar growth to the UK before the 2016 vote to show the divorce was responsible for an 8% hit to GDP. It also tested firm-level data using the BOE’s closely watched Decision Maker Panel survey and figures from business accounts: a method that showed a 6% blow.

The US has advantages the UK wouldn’t have been able to count on in the post-Covid geopolitical landscape, including energy independence that shielded it from the spike in fuel prices that followed the Russian invasion of Ukraine. But even when excluding the US from the so-called doppleganger UK in his own study, the CER’s Springford still sees a hit to GDP of 4.7% by mid-2022.

The no-Brexit UK economy keeps pace with US growth rather than languishing alongside underperforming Europeans. When countries are randomly excluded from repeated iterations under the same methodology, the range of impacts on the UK range from 3% to 6.7%, suggesting major damage even in the smallest estimate.

The government’s official forecaster, the Office for Budget Responsibility, predicted a 4% impact on long-run gross domestic product and a 15% blow on trade 15 years on from the exit. Although academics are seeing a sharper blow emerging in the GDP data, they’re observing a less damaging picture on goods trade.

WATCH: What’s the solution to Britain’s growing economic crisis?Source: Bloomberg

Former Conservative Chancellor — and remain supporter — Jeremy Hunt said earlier this year that many claims about leaving the EU had been “overly exaggerated.” He wrote in the introduction to a Policy Exchange report: “Brexit has had much less impact on British exports to the EU than has been previously thought.”

That’s also what economists see — yet their conclusions still make for grim reading. Work by authors including Rebecca Freeman of the Bank of England and Thomas Sampson from the London School of Economics finds that the largest UK firms saw little impact on their exports to the EU but the the small and medium-size businesses suffered big drops, including a 30% plunge for the smallest fifth.

Overall they found a 6.4% reduction in worldwide UK exports and a 3.1% drop in imports. “No one in the UK wanted to invest because they didn’t know what the future would look like,” Sampson said.

An explanation for the different trajectories of growth and trade data is that the latter will take longer to show: small firms that once would have grown their businesses through trade with the EU may not start exporting to the region in the first place. Larger ones may continue, but at greater expense.

“We don’t think that the effect on trade has been anywhere near as strong, I think, as people were expecting,” said Stephen Millard, deputy director at the UK’s National Institute of Economic and Social Research. “That doesn’t really capture the fact that you can continue trading but it’s just costing you more.”

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2025 Bloomberg L.P.