In a responsum about whether or not it is permissible to cheat on the New York State Regents exams, Rav Moshe Feinstein described the United States as a malchut shel chesed, a kingdom of kindness. Rav Moshe was born in Tsarist Russia in 1895 and lived there until pressure from the Soviet regime forced him and his family to flee to New York in 1937, where he lived for the rest of his life.

Rav Moshe’s perspective was clearly a product of his lived experience. He went from the religious suffocation of communist Russia, where, for example, the mikvah in the town of Luban, where he served as the rabbi, was destroyed, to the religious liberty of the United States. In Rav Moshe’s words, “[The] entire goal” of his new home “is to benefit the residents of the country.” That the United States is a kingdom of kindness is obvious.

However, we cannot ignore that whatever Rav Moshe and generations of refugees may have felt in the past, today American Jews find themselves facing conflicting evidence.

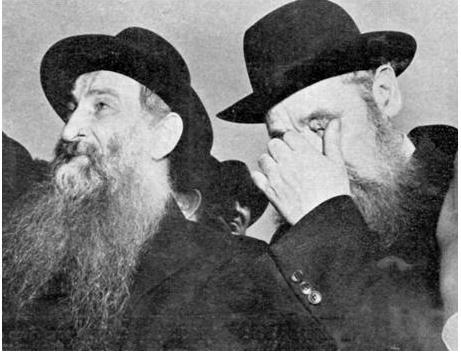

In the last generation, the United States, whose military liberated Dachau in April 1945, was the same nation whose president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, turned away hundreds of rabbis — Rav Moshe Feinstein among them — who came to the capital in October 1943 to lobby for the U.S. to bomb the railways leading Jews to their deaths at Auschwitz.

My question is not how we should relate to the government or to the citizenry of the United States, or even the unique culture of this country, which seeps into every realm of our lives. My question is a result of the confluence of these factors: How should Orthodox Jews relate to the United States as a concept, as an organism?

Is it incumbent upon us to echo the sentiments of Rav Moshe, recognizing that when we take a bird’s-eye view of Jewish history, from Ferdinand and Isabella’s Spain to Hitler’s Germany, America stands above the rest as a city on a hill? Or may we allow ourselves to adopt a more narrow approach focused on the last decade of American Jewish history, during which antisemitism has risen precipitously and a man who refuses to condemn the phrase “Globalize the Intifada” has become mayor of New York? We now live in an America where antisemitism has transitioned from an ideology that remained on the periphery of society to one that has become vaguely trendy if you happen to find yourself in the right place.

It is these two poles, standing on opposite ends, which compel me to ask: How should we, as American Orthodox Jews, relate to the United States? I have seen a wide spectrum of emotions and attitudes, ranging from extreme apathy and nonchalance to intense patriotism and pride. Aside from individual feelings that I have heard in conversations around the shabbat table, we know that the sentiments we hear now also lead to a different calculus at the ballot box. For example, to what extent does one factor in the potential health or harm that a candidate may cause to America’s democratic institutions? Does one vote at all? How does one approach these questions, not from an entirely pragmatic and self-serving perspective (although I do not think that seeing government that way is entirely bad) but rather from the perspective of simply identifying with the United States in some capacity, not merely as someone who happens to be a citizen but rather as someone who actively and intently identifies as an American? When America prospers does one feel satisfaction? When America is in decline do they feel embarrassed?

Ultimately, eilu v’eilu, both these and those. Both as Jews and more broadly as American citizens, we enjoy unparalleled comfort, prosperity and economic opportunity. Sometimes I feel it is a blessing that spray-painted swastikas, tragic as they may be, are newsworthy, because it is a sign of how anomalous antisemitism still is in America. It was only one generation ago that my uncles, growing up in London in the 1980s, were beaten up on a regular basis and called “Yido” in the street. Such events never made it into the papers. This behavior was simply par for the course. More broadly, as Americans and not just Jews, what great benefits we have become numb to: Long gone are the days of sky-high infant mortality rates and lives spent battling infectious diseases of every kind. Physical health and material well-being is better than it ever was in the shtetl. When was the last time anyone you know had to be treated for typhus?

But there is no doubt that with Mamdani’s election, as well as with other political trends such as the increasingly inevitable blowback that some lawmakers face for supporting Israel or the alarmingly legitimizing rhetoric with which politicians relate to terrorists who seek Jewish demise and death, Jews now walk the streets of America with more trepidation than we once did. A balance between deep gratitude and appropriate apprehension is one we must strive to strike. It is easy for one to consume the other, as recognition of the bountiful blessings of America may blind us to real dangers and appropriate caution, while paranoia and anxiety may lead to an incorrect ignorance of what America has given us. Our mission now lies in guarding from either extreme, blind patriotism or complete ingratitude, and staying the center as we wait and see what the future holds for American Jewry.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Washington Daily News – Oct. 7, 1943

Photo caption: Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz, left, with another rav, at the Rabbis March on Washington in 1943