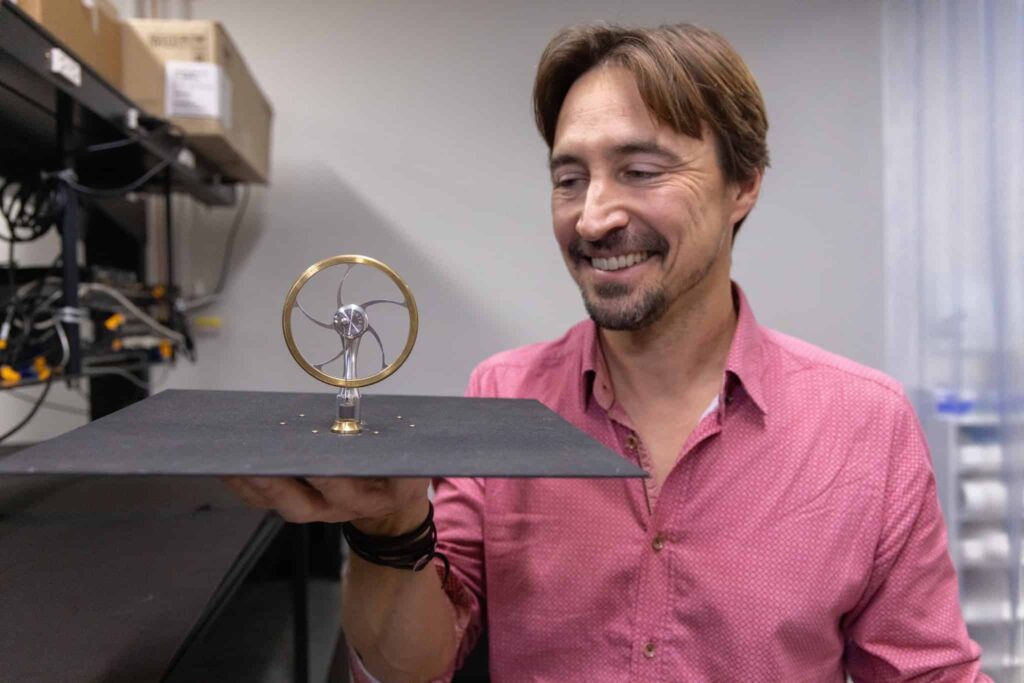

UC Davis engineering professor Jeremy Munday has developed an experimental engine that can generate mechanical power from the temperature difference between the Earth and deep space when placed outdoors at night. Credit: Mario Rodriguez/UC Davis.

UC Davis engineering professor Jeremy Munday has developed an experimental engine that can generate mechanical power from the temperature difference between the Earth and deep space when placed outdoors at night. Credit: Mario Rodriguez/UC Davis.

When the sun sets, the world’s solar panels go dark. But above them, the night sky radiates a different kind of power. Every night, as the world cools, Earth dissipates much of its heat into space. The invisible stream of infrared radiation escaping our planet has been, until now, mostly untapped. That’s until engineers at the University of California, Davis, entered the picture by building a small machine that captures this outward flow of energy and turns it into motion — and, ultimately, electricity.

The invention is a simple, elegant twist on an old-school technology: a Stirling engine. This isn’t a massive, complicated semiconductor electronic rig. Instead, it uses a mechanism that is “mechanically simple and [does] not rely on exotic materials”. The machine essentially runs on the temperature difference between the ground and the open sky.

The core idea flips the script on how we think about energy collection. Professor Jeremy Munday, a co-author on the paper, says that thermoradiative devices function “like solar cells in reverse.” He adds, “Rather than pointing them at a hot object like the sun, you point them at a cool object, like the sky.”

The Engine That Works in Reverse

The device resembles a pinwheel. Credit: Jeremy Munday.

The device resembles a pinwheel. Credit: Jeremy Munday.

In a Stirling engine, first conceived in the early 19th century, a sealed chamber of gas expands when heated and contracts when cooled, pushing a piston back and forth. “These engines are very efficient when only small temperature differences exist, whereas other types of engines work better with larger temperature differences and can produce more power,” Munday explained.

UC Davis version has its “cold” side painted with a heat-radiating coating that beams infrared energy into the sky. Its “warm” side sits on the ground, soaking up ambient heat. That small gradient — often no more than 10 degrees Celsius — can keep the piston turning through the night.

The top plate (warm side) uses a paint that is highly emissive in the infrared. This allows heat to pass directly through a clear section of the atmosphere, called the atmospheric transparency window (between 8 and 13 µm). The heat radiates directly into space, cooling the panel far below the ambient air temperature.

“It doesn’t actually have to touch space physically, it can just interact radiatively with space,” Munday explains.

Over a year of outdoor experiments in Davis, California, the device consistently generated more than 400 milliwatts of mechanical power per square meter. It even powered a small fan and, when coupled to a tiny DC motor, produced electrical current. The experiments revealed that performance peaks in clear, dry summer nights and dips in humid, cloudy winter conditions because water vapor in the air blocks the infrared radiation escaping to space.

Four hundred milliwatts per square meter is only about one-hundredth of what a modest solar panel can produce in full sunlight. The upside is that thermoradiative devices can operate at night, without batteries or fuel. The trickle of mechanical or electrical power they provide is still useful in rural areas, deserts, or even deep space habitats.

Turning Nighttime Chill into Useful Work

The new device generates mechanical power directly. This is perhaps its strongest point because, as Munday mentions, it means the power is “valuable for applications like air movement or water pumping — without needing intermediate electrical conversion.”

In one demonstration, graduate researcher Tristan Deppe swapped the flywheel for a 3D-printed fan. Inside a simulated greenhouse, the fan spun fast enough to move air at 0.3 meters per second — enough to circulate carbon dioxide around plants and prevent hotspots from forming.

At higher temperature differences, the device achieved airflows exceeding five cubic feet per minute, meeting the minimum standard set by the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) for maintaining healthy indoor air circulation in public buildings.

In global simulations based on NASA’s energy and temperature data, Deppe and Munday found that their device would work best in arid regions and mountain ranges — Saharan Africa, the Eurasian Steppe, or even summer Antarctica — where humidity is low and the night sky is especially transparent.

The researchers also note that radiative cooling itself could help offset Earth’s energy imbalance: our planet currently absorbs about one watt per square meter more than it emits, driving global warming. By converting some of that trapped heat into mechanical work, their engine effectively prevents a fraction of it from re-entering the atmosphere.

Deppe and Munday estimate that the system could potentially scale to six watts per square meter under optimal conditions. Future improvements might involve swapping the working air for helium or hydrogen to reduce friction, using copper for better heat transfer, or adding thermally insulated radiators to boost output during both day and night.

The findings appeared in the journal Science Advances.