Peter Kellner, one of the most experienced opinion pollsters in the UK, has been revisiting the public opinion numbers on Brexit, with some striking results. He now believes that public opinion in Britain has shifted strongly against Brexit for two reasons: generational change and Leave voters changing their minds. It could give ministers a real chance to move towards much closer economic ties with the EU, but only if they can sell a vision bold enough to satisfy a Rejoin majority, and consolidate the Leavers who have changed their minds.

How the numbers have shifted

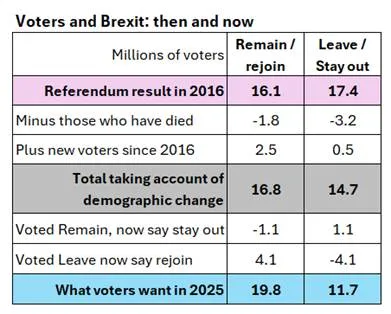

In 2016, 17.4 million people voted Leave and 16.1 million voted Remain, giving Leave a 1.3 million lead. Since then, about six million Britons have died, mostly older voters who were more likely to turn out. Of these, 3.2 million were leavers, and only 1.8 million Remainers. Kellner estimates that among those who voted in 2016 and are still alive, Remain and Leave are now roughly tied, with around 14.3 million former Remain voters and 14.2 million former Leave voters still living.

But young people reaching voting age have tilted the balance further. Around six million new voters have joined the electorate since 2016, and polling suggests that an overwhelming majority favour rejoining the EU, perhaps by five to one. And even with a generous allowance for lower turnout he estimates that 2.5 million young people would vote for Remain and only half a million for Leave.

So, adding these two sets of figures, the current balance might be around 53:47: 16.8 million for Remain/Rejoin and 14.7 million for Leave.

As he points out, ‘respecting the referendum result’ now means “a belief that the votes of the dead count for more than the views of the young”.

Voters changing their minds

But this assumes that nobody has changed their mind. And polling suggests that many have, though in both directions. YouGov finds around 8% of those who voted Remain now saying they would keep Britain out of the EU, but 29% of those who voted Leave now saying they would opt to rejoin. That equates to roughly 1.1 million Remainers switching to Leave and 4.1 million Leavers moving to the pro-EU side. When these “switchers” are added to the demographic effects of deaths and new voters, the original 1.3 million Leave majority turns into an estimated pro‑rejoin majority of about 8.1 million people. Of course, these are estimates, not precise counts, but the shift is too large to be explained away by polling error or small sampling problems.

The table shows how these two changes together give us a 63:37 split in favour of Remain/Rejoin. Kellner points out that no UK election in history has ever produced such a clear cut result.

KellnerEconomic impact of Brexit

KellnerEconomic impact of Brexit

So why have so many Leave voters changed sides? Polling suggests that only a quarter of them think Brexit has been a success, while more regard it as a failure, mainly because they think it has hurt the economy and failed to deliver extra money for the NHS.

Before Brexit fully took effect, many economists expected a long‑term hit to UK GDP of 4–5%. A more recent study by a team including a Bank of England economist estimates the economy is now about 8% smaller than it would have been without Brexit. And the gap is widening over time.

In money terms, that is already around £240bn a year in lost output. On typical tax ratios, this implies perhaps £80–100bn a year less in government revenue, money that could otherwise support hospitals, schools, defence, policing and anti‑poverty measures.

Limited gains from Starmer’s “reset”

Labour’s government has already negotiated a modest “reset” of EU relations, promoted as good for business, jobs and people’s pockets. This has included practical improvements such as making food and drink exports a little easier. However, when Kellner asked exporters interviewed earlier in the year, they welcomed the changes but saw them as only minor improvements. This was mirrored by the Centre for European Reform, which projected that the planned ‘reset’ might raise long‑run GDP by only 0.3–0.7%. That would claw back less than a tenth of the estimated Brexit damage.

A “game‑tweaker”, not a game‑changer.

What the government would need to do

Politically, the crucial group is the roughly four million former Leave voters who now favour closer ties or rejoining. Even without them, the split would still be 53:47 for Rejoin, but a much more fragile basis for action. So, Kellner argues that, to keep these voters, ministers must present a credible plan to repair most of the Brexit damage, not just trim at the edges.

That probably would mean restoring frictionless trade with the EU, which implies something like rejoining the Single Market and/or Customs Union, even if under a different label. But doing this would mean accepting EU trade rules and the authority of the European Court of Justice, as well as the sensitive issue of contributing to EU funds.

It’s also worth pointing out (which Kellner doesn’t mention) that a change in rules for General Elections has refranchised 2 million UK voters living overseas, many of them in Europe. It’s likely that a majority of these would be in favour of Rejoin.

The political task, therefore, would be to persuade voters that higher growth, better jobs, improved living standards and more funding for public services are possible and worth some loss of formal sovereignty. Although government statements recently have seemed much warner to the EU, it remains to be seen whether they really have the courage, clarity and confidence to sell a vision of a relationship with the EU that matches where public opinion has now arrived.

Peter Kellner’s substack on this can be found here.

More from East Anglia Bylines Subscribe to our newsletters

Subscribe to our newsletters

Each of our Bylines sends a newsletter every month and we also send out a ‘Best of Bylines, featuring a selection of the best articles from across the network