Andrew M Dorman reflects on UK defence policy and argues that while the UK must deintegrate its defence capabilities from the US and implement the recommendations of this year’s Strategic Defence Review more quickly, there are economic tradeoffs.

Since Donald Trump began his second term as US president, Keir Starmer and many of his fellow European leaders have acted as if in 2029 there will be some form of return to ‘normality’.

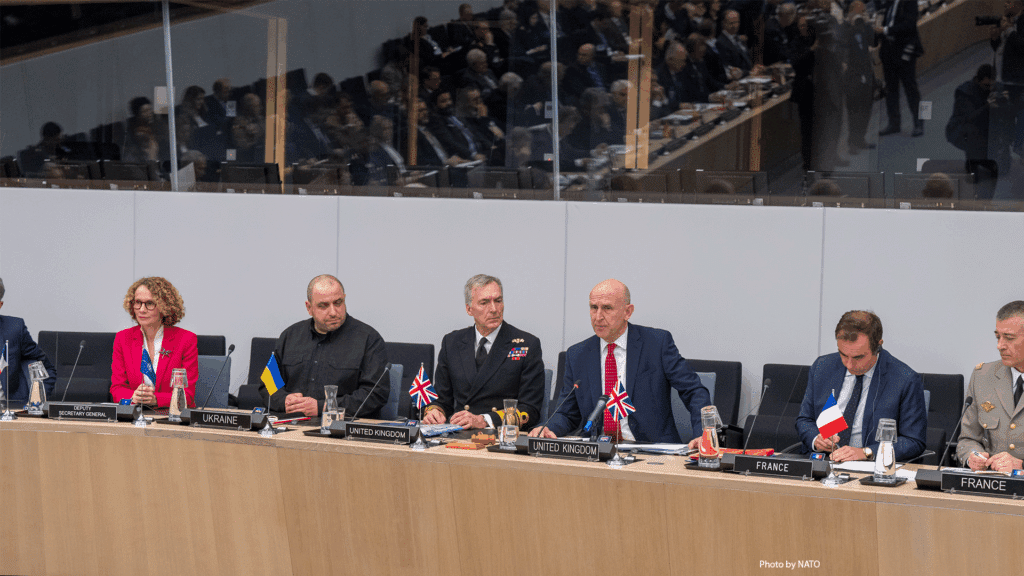

Starmer has continued the policies of his Conservative predecessors. Through a royal visit, promises to increase defence spending and an absence of criticism, Starmer has hoped to minimise US tariffs on the UK, keep the US in the NATO alliance and supportive of Ukraine in its war with Russia. He has also repeated the standard British strapline emphasising the importance of the UK remaining Europe’s leading military power and some form of bridge between the US and Europe.

Whilst the on-off alignment of the US with the Russian position on Ukraine has been a real concern, the new US National Security Strategy marks a major change in US foreign policy. Its language is deeply antagonistic towards Europe, including the United Kingdom, and has been well received in Russia. It speaks of US involvement in European domestic politics in support of more nationalistic, extreme parties and questions the NATO Article V guarantee.

For the United Kingdom this represents a further nail, if not the final nail, in the coffin of the US-UK special relationship and America’s walk away from the defence of Europe. The United States can no longer be relied on to help defend the West and its values. Rather any US involvement will be on a transactional basis, and the United Kingdom needs to rapidly unpick 80 years of defence integration with, and dependence on, the US. This is no small task and will need to be undertaken in partnership with the UK’s European allies. The failure to do so will leave the UK isolated and entirely dependent on the whims of the US presidency. To date, there is no evidence that Starmer has taken on board this new reality.

Since taking office Starmer’s government has undertaken an externally led Strategic Defence Review (SDR) which has emphasised both the near time threat posed by Russia and a longer-term one posed by other authoritarian governments such as China, Iran and North Korea. All of this has been accepted mainstream orthodoxy within Britain’s wider defence establishment.

His government has accepted the SDR’s recommendations, including continuing the replacement of the UK’s nuclear capabilities, starting to develop a second nuclear delivery system, providing a reserve corps of two army divisions and significantly enhancing Britain’s maritime contribution to the North Atlantic and Norwegian Sea. The government has pledged to increase defence spending to 2.5% of GDP by 2027, and 3% by the end of the parliament. They have also committed to the new NATO 3.5% target for direct defence spending plus an additional 1.5% on defence related infrastructure by 2035.

The problem is the glacial pace of delivery, largely caused by a lack of money. For example, construction of six new munitions and energetics factories to allow the UK to produce enough munitions in wartime has yet to start and orders for the replacement for the AS90 self-propelled guns given to Ukraine have yet to be made leaving the British Army desperately short of artillery. The promised Defence Investment Plan is rumoured to be unaffordable with a basic choice boiling down to whether the UK has an army or navy based on current planned funding levels. Moreover, within the SDR there is no sign of any prioritisation amongst the 60+ recommendations

With Christmas fast approaching Keir Starmer has a defence dilemma before him. He is confronted with Russia engaged in sub-threshold warfare with much of the west and the potential for a real war with Russia in the next 5 years. For example, mysterious drones have been seen over the French nuclear submarine base, over airfields in Belgium and Denmark and the Republic of Ireland whilst ships linked to Russia continue to snag undersea cables. The new US National Security Strategy attacks Europe and Trump continues to question NATO’s Article collective security guarantee. At the same time, the British economy is struggling to recover from the effects of Covid-19 and leaving the single market. The UK has high levels of overall debt and a current account deficit of around 4.5%. It has crumbling infrastructure and social services in need of additional resources.

In some ways the situation is reminiscent of the position that Clement Attlee, one of his Labour predecessors, found himself in in 1950. Attlee was confronted with the outbreak of the Korean War, real fears of a third world war (see the 1950 Defence and Global Strategy Paper), a nation recovering from the effects of World War II including the continuation of rationing, war damaged infrastructure, a high level of national debt and social services in need of investment. Attlee’s solution was to embark on rapid rearmament on a scale far higher than NATO’s 3.5+1.5% target to help deter war paid for, in part, through taxation such as the introduction of prescription charges.

Britain’s European allies in Scandinavia, the Baltic States, Poland, Germany and France have all responded to the threat posed by Russia with significant increases in defence spending. The question for Starmer is whether to do likewise, fully fund rearmament and maintain Britain’s position as Europe’s leading military power and supporter of Ukraine or to dither, obfuscate and leave the UK dependent on a disdainful US ally who will decide on the day whether to help.

By Andrew Dorman, Professor of International Security, King’s College London.