The Wendelstein 7-X (W7-X) is the largest and most advanced stellarator in the world, and on its tenth birthday, it’s clear the experiment has graduated from a bold engineering prototype to a running laboratory that can teach fusion physicists how to keep plasmas hot and steady for the long timescales a power plant would need.

Unlike tokamaks, which rely on a large, current-driven plasma to shape the confinement field, stellarators use a web of external, permanently wound coils to generate a three-dimensional magnetic cage. That complexity makes the machine extremely hard to design and build, but also gives stellarators a fundamental advantage.

By removing the need for a large internal plasma current, they can, in principle, avoid some instabilities that limit continuous operation in tokamaks. The W7-X was built specifically to test whether an optimised stellarator configuration can match, or even outperform, tokamaks in terms of confinement and steady-state operation.

From concept to reality: a decade of painstaking engineering

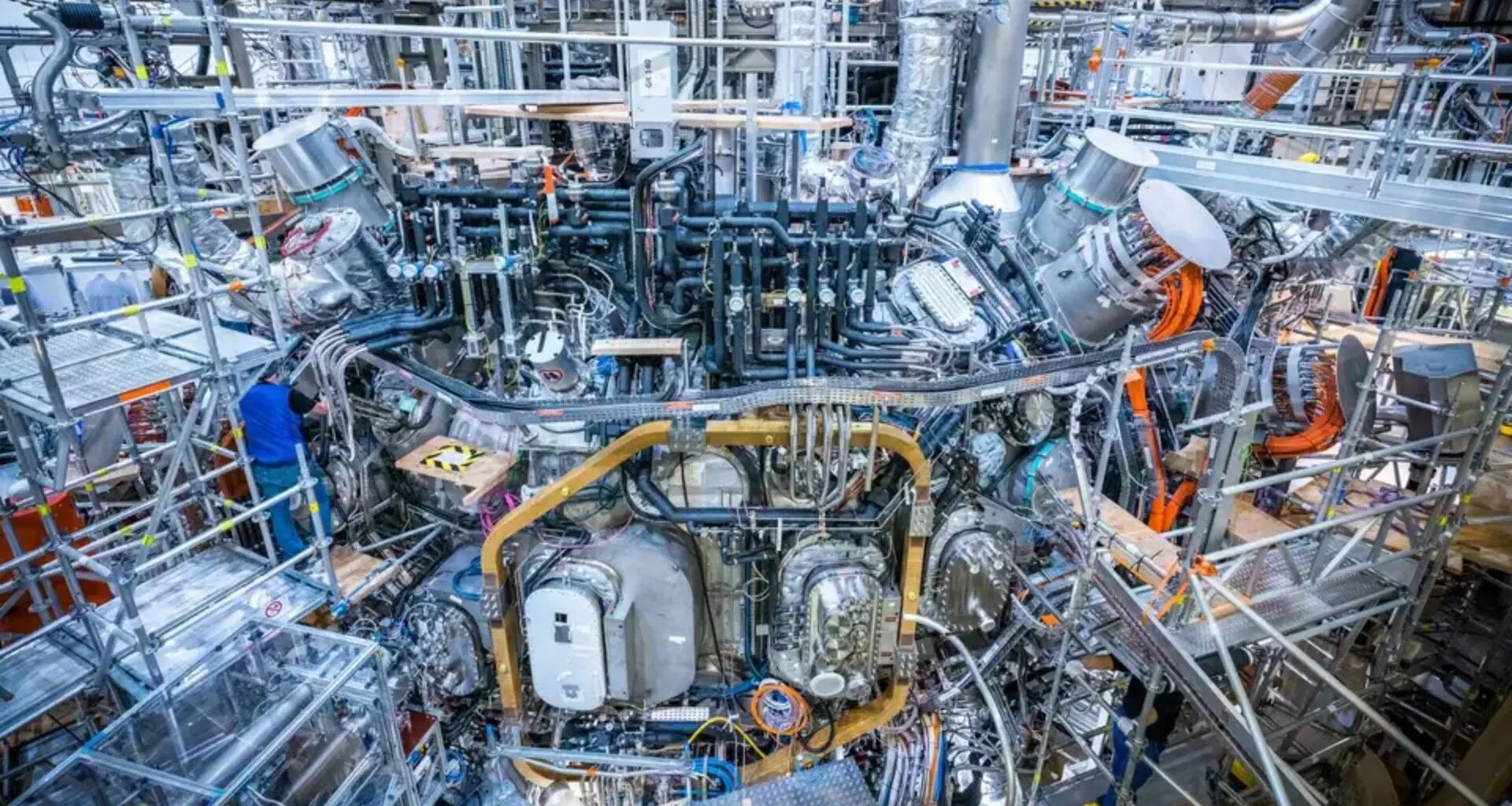

The first research plasma in W7-X was produced on 10 December 2015, a milestone that followed years of design work, precision manufacturing, and international collaboration. The machine’s 50 non-planar superconducting coils are shaped to within millimetres to produce the carefully calculated twist in the magnetic field.

Assembling the vacuum vessel and cryostat around that coil system was a unique effort. Those opening pulses were a proof-of-concept. They showed that the coils, control systems, and diagnostics worked together. But they left the central question open. Could a stellarator sustain high-performance plasmas long enough to be relevant for a future power plant?

The 2025 leap: beating long-pulse records and the triple product

In 2025, the W7-X team answered that question with results that changed how people judge stellarators. During the OP2.3 experimental campaign, the device sustained high-performance plasmas for unprecedented durations and recorded a world-record value of the so-called triple product (density × temperature × confinement time) for long plasma discharges.

On 22 May, the team ran plasmas that maintained that elevated triple product for 43 seconds. A duration long enough, researchers say, to observe the transport and stability physics relevant for reactor operation and to compare stellarator performance directly with long-pulse tokamak results.

Those experiments included pellet fueling at high speed and bursts of microwave heating to keep the plasma hot, coordinated precisely to address the two most stubborn problems in fusion research. Fueling and heat exhaust.

The new record puts the W7-X triple product on par with the best tokamak results for similar pulse lengths and demonstrates that optimising three-dimensional fields can yield confinement comparable to that of tokamaks.

What the measurements mean, and what they don’t

The triple product is a shorthand for fusion progress. To make net energy, you need enough particles at high temperature held together long enough for fusion reactions to occur. Hitting tokamak-level triple products at tens of seconds doesn’t mean commercial fusion is around the corner, but it is a crucial proof point.

The W7-X results show the stellarator path can reach the same physics regime as tokamaks while offering a route to steadier operation. The experiments also produced fast helium-3 ions and demonstrated improved control over edge conditions and heat loads, both of which are vital for transitioning from short experimental pulses to continuous operation. These are engineering and physics milestones that reduce one class of unknowns for stellarator-based reactors.

Remaining challenges and the roadmap ahead

The W7-X itself is not designed to be a power-producing device. Its mission is to illuminate the physics and engineering choices that would go into a future stellarator power plant. Key challenges include handling continuous high heat fluxes on plasma-facing components, developing robust, long-lived wall materials and coatings, and scaling the machine design to reactor sizes while keeping complexity and cost manageable.

The IPP team has emphasised that the W7-X is entering a maintenance and upgrade phase and that experiments are planned to resume after system work to address such engineering issues. In parallel, several start-ups and engineering teams are already using W7-X data to inform conceptual power-plant designs, which shows us the experiment’s role as an incubator for both industry and academia.

Why W7-X matters for fusion strategy

Large, international tokamak projects (notably ITER) sit alongside national and private efforts exploring alternative confinement schemes, advanced materials, and novel fuels. W7-X’s significance lies in turning a theoretical idea into experimental data that engineers and companies can use. The idea is that optimising the three-dimensional magnetic geometry can reduce transport and enable steady operation.

If stellarators can deliver tokamak-level performance without requiring large, unstable plasma currents, they offer a compelling complement to the tokamak roadmap. One that may be better suited to continuous baseload power and easier integration with industrial plant systems. That potential is why a decade after its first plasma, W7-X remains central to the global fusion conversation.

A decade on, the point is pragmatic

Wendelstein 7-X’s anniversary marks progress in a field where incremental, hard-won advances matter. The machine’s recent records show that the stellarator approach can compete on the physics that matter for a reactor, and that it converts years of computational design work into hands-on operational experience.

For engineers and funders, this shifts the question from “can a stellarator work?” to “how do we build one that is economical, maintainable, and scalable?” That is the practical question fusion researchers will be tackling in the next ten years, and W7-X has just made that debate far more interesting.