WANA (Dec 14) – In the recent meeting between Vladimir Putin and Masoud Pezeshkian, one issue came up more than any other: the Rasht–Astara railway.

So important, in fact, that the Russian president personally asked about its progress, and the Iranian president replied: “I follow this project every week.”

This mutual emphasis is no coincidence. Rasht–Astara is not just another infrastructure project or a routine railway line; it is the missing link in one of the most consequential geopolitical equations of the 21st century: the North–South Transport Corridor.

Russian President Vladimir Putin and Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian meet in Moscow, Russia January 17, 2025. Handout / WANA News Agency

Why is Putin so focused on this corridor?

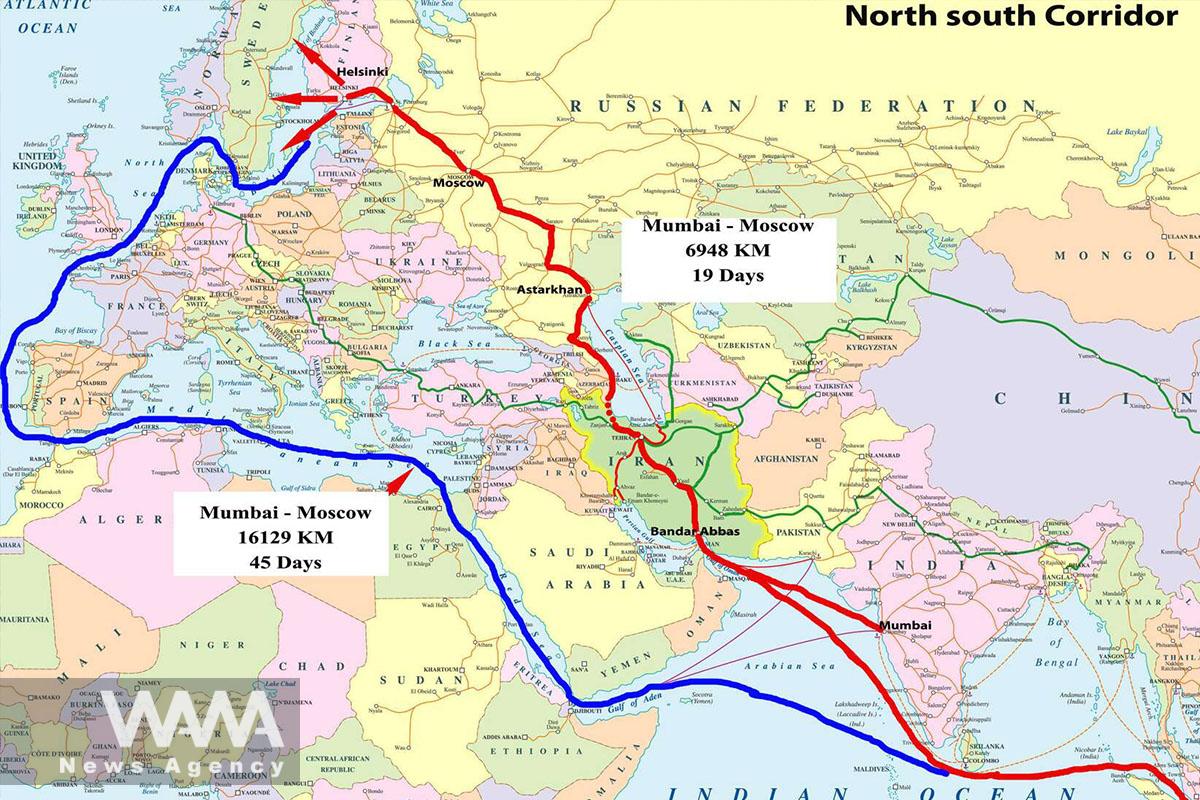

Russia today faces an unprecedented geopolitical squeeze. Its access to warm waters is effectively confined to the Black Sea route—a route that passes through the Bosphorus and Dardanelles under Turkish control, reaches the Mediterranean, then must go through the Suez Canal, enter the Red Sea (now increasingly insecure), pass Bab el-Mandeb, and only then reach the Indian Ocean.

This route is:

- Long

- Expensive

- And, most importantly, insecure

For a country whose economy depends heavily on energy and commodity exports, this translates into strategic vulnerability.

The North–South Corridor fundamentally alters this equation. Once the Rasht–Astara railway is completed, Russia’s rail network will be directly connected to Bandar Abbas. In practical terms, this means Russia can move goods and energy to India, South Asia, and even East Asia faster, cheaper, and far more securely.

For Moscow, this is not merely about economic efficiency; it is a way out of a geopolitical dead end.

WANA (Nov 29) – During the 83rd meeting of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) Transport Council in Baku, the heads of the railways of Iran, Russia, and Azerbaijan signed a strategic trilateral memorandum of understanding to develop the western route of the North–South international transport corridor. The railway agreement marks a milestone in […]

What does Iran gain from this project?

At first glance, the answer seems straightforward: transit fees, revenue, and jobs. But the true significance of the North–South Corridor for Iran goes well beyond economics.

Once this route becomes fully operational, Iran shifts from being a “peripheral country in global trade” to an unavoidable hub linking Eurasia to South Asia. Put simply, a significant share of Russian, Indian—and potentially future Chinese—trade becomes tied to Iran’s stability and security.

This marks a clear paradigm shift: Iran’s security becomes inseparable from the security of major powers’ trade flows.

Under such conditions, instability in Iran is no longer just a “domestic issue” or a tool of political pressure; it directly threatens the economic interests of major actors. This is the point at which geopolitics turns into a form of deterrence.

WANA (Nov 25) – A relatively under-reported development in the heart of Eurasia has recently begun to draw the attention of world capitals: Iran’s gradual return to the map of real global trade flows. The corridor that starts in Xinjiang, crosses Central Asia, enters Iran, and continues to Turkey had remained a blueprint for […]

Iran has already leveraged a less visible asset for years: its airspace. Thousands of international flights crossing Iranian skies generate revenue and confer strategic importance. Closing that airspace carries direct costs for others.

The North–South Corridor applies the same logic on land and rail. When Iranian railways become a primary artery for global trade, Iran gains a silent lever of influence—one that requires neither military threats nor overt political confrontation.

This is precisely what elevates Iran’s position even vis-à-vis its regional rivals in the Persian Gulf, many of whom are consumers of trade routes rather than owners of them.

Why was this project stalled for 30 years?

This question may be even more important than the project itself.

The North–South Corridor is not a new idea. It has been on the table for decades. So why did it fail to advance?

The answer likely lies in a combination of:

- Overreliance on oil revenues

- Weak strategic prioritization

- And resistance from actors who had no interest in Iran becoming a global trade hub

A country that controls key trade routes is not easily marginalized—and that is precisely what some preferred to prevent.

What has changed today is not just technical progress, but the level of political commitment. Official figures indicating the acquisition of more than 106 kilometers of the 162.5-kilometer Rasht–Astara route, combined with the Iranian president’s insistence on weekly oversight, signal that this time the project is being treated as a strategic priority, not merely a construction effort.

When Putin focuses on the numbers and Pezeshkian responds, the message is clear: this project has moved from the margins to the core of policy.

What comes next?

The next step for Iran goes even further. If the North–South Corridor links Iran to Russia and India, an East–West corridor could connect Iran to China and Europe. A fully integrated China–Iran–Turkey rail network would have an even greater impact—economically and strategically.

In that scenario, Iran would no longer be just a corridor, but a continental crossroads.

Ultimately, this project is an attempt to convert Iran’s geography into lasting power—a form of power that generates security, revenue, and influence without firing a single shot.