It has been 130 years since the SS Germanic passenger liner crashed with the Cumbrae in the Crosby Channel An artist’s depiction of the Germanic moments before crashing into the Cumbrae, published in The Graphic, 1895(Image: The Graphic)

An artist’s depiction of the Germanic moments before crashing into the Cumbrae, published in The Graphic, 1895(Image: The Graphic)

Throughout the long history of the White Star Line, Liverpool’s once-thriving shipping line that dominated oceans all over the world, the sinking of the Titanic in 1912 is undoubtedly its most infamous disaster, resulting in the deaths of up to 1,635 people. Other major losses, such as the SS Atlantic, the RMS Republic, and the Brittanic in WWI also received major attention, and have cemented their place in maritime history.

But one White Star Line disaster has apparently fallen out of memory. It has been 130 years since the Germanic passenger liner crashed with the Cumbrae, an inward-bound Glasgow steamer, in the Crosby Channel on December 11 1895.

The disaster was reported widely at the time, appearing in both British national newspapers and The New York Times, as the Germanic was bound for New York. But it was quickly overshadowed, possibly due to an incredible stroke of luck: not a single person died.

According to contemporary reports, the two vessels were navigating in heavy fog when they collided around eight miles off the coast of Crosby. The Cumbrae didn’t stand a chance as the enormous cruiser ploughed 14ft deep into its side, and it rapidly started to sink.

The Germanic was commanded by Captain Edward R. McKinstry, and its passengers were among the privileged classes of both Britain and New York. On board was Lord Dunraven, a member of the House of Lords and former Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, and members of the John Hare theatre company, including leading West End actress Ellis Jeffreys.

The Cumbrae, meanwhile, was a humble passenger ferry commanded by a Captain Blair. It was on the last leg of its journey, transporting a small theatre company from Glasgow to Birkenhead, where they were due to perform the ironically named “Saved from the Sea”.

Ronald Noon, a former history lecturer at John Moores University, began looking into the crash following his research into the “Rolling Stonemason” Fred Bower, who cut the first stone on the site of Liverpool Cathedral. Bower was onboard the Cumbrae, and provided a first-hand account of the rescue as ropes and ladders were thrown onto the Cumbrae’s decks, and passengers scrambled aboard the Germanic.

Ronald said: “I thought, especially with the anniversary coming up, what an incredible story. I looked at the New York Times and I looked at Liverpool records. You think back to a time before social media.

“The first thing that struck me was this magnificent drawing that I really latched onto – it was in The Graphic (a British weekly illustrated newspaper founded in 1869). That incredibly well-crafted drawing was like a freeze frame of all the people onboard the SS Germanic.

“There are varying reports of the number of people onboard the Cumbrae, which was just a ferry passenger, but it looks as though they all survived. Maybe that’s why it hasn’t stayed in the public eye, because there weren’t any deaths. But it was just half an hour before it sank, and it actually remained six miles out, not far out from Waterloo.”

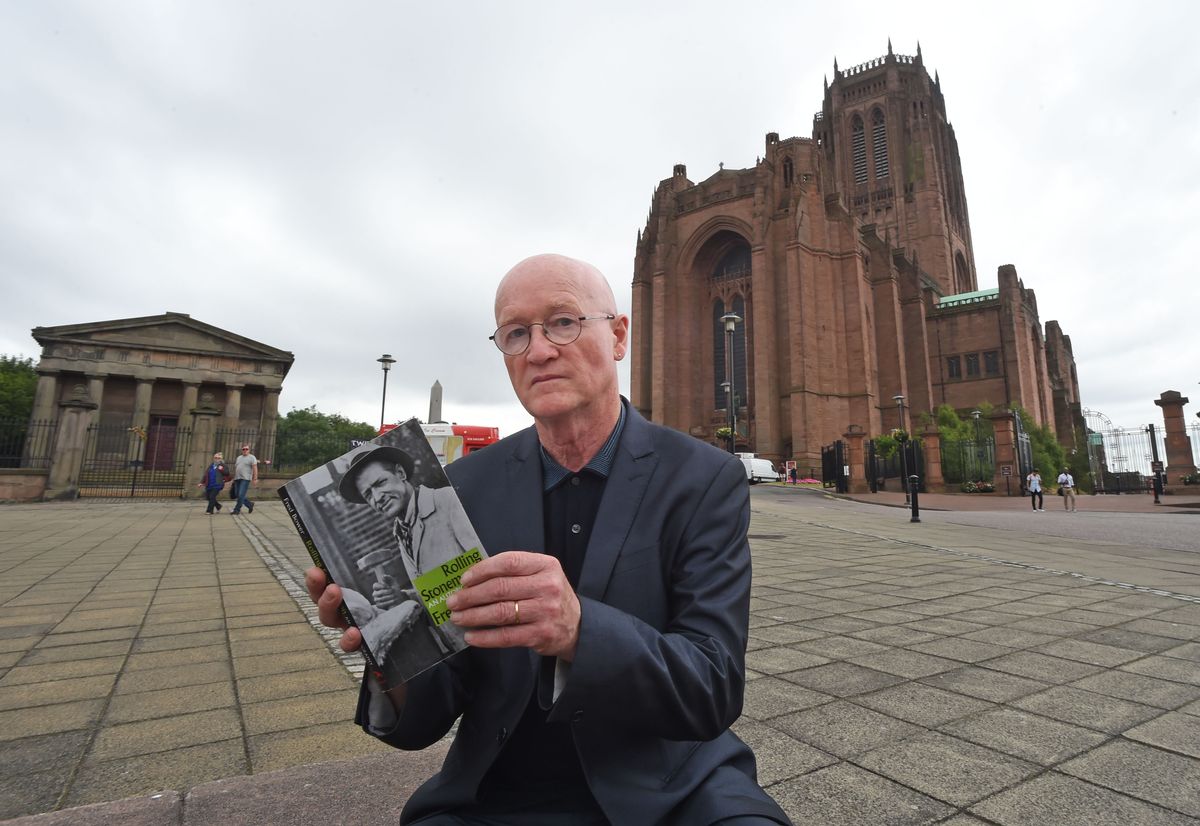

Author Ron Noon at Liverpool Cathedral and his publication about Liverpool stonemason Fred Bower(Image: Colin Lane)

Author Ron Noon at Liverpool Cathedral and his publication about Liverpool stonemason Fred Bower(Image: Colin Lane)

The sinking of the Cumbrae, he said, casts a new light on Joseph Bruce Ismay, the chairman of the White Star Line. Ismay’s reputation was shattered after the Titanic sank in 1912, and it emerged that he was the one who authorised the number of lifeboats to be reduced from 48 to 16.

He was further criticised for deserting the ship while women and children were still on board, escaping in a lifeboat less than 20 minutes before the ship went down. Some papers called him the “Coward of the Titanic ” or “J. Brute Ismay”.

But 17 years earlier he did an “amazing job”. Ronald said: “J. Bruce Ismay was exemplary in 1895 because he actually went out on a tugboat to check the people on the SS Germanic. He went back to Liverpool, he sorted them out in the two big hotels, the North Western hotel and The Adelphi, and what ships they were going to get to New York on.

Joseph Bruce Ismay, who travelled on (and survived) the maiden voyage of his company’s ocean liner, the RMS Titanic, in 1912

Joseph Bruce Ismay, who travelled on (and survived) the maiden voyage of his company’s ocean liner, the RMS Titanic, in 1912

“The Germanic was built 1874 but had just been refitted and was in absolute luxury. Liverpool was the New York of Europe.

“When you look at Liverpool history, what some people might call local history is invariably more than that. It always has international links, whether you’re talking about the slave trade or something else.

Liverpool was not just wealthier than Manchester at the time; the concentration of wealth was incredible. But there was a stark contrast between riches and poverty and in a sense what I’m intrigued by was how this was reflected in the tale of two ships.

“In 1895, we’re talking about Liverpool really in its pomp. We’re a port city, it’s a different type of social geography. There’s a big part of Liverpool that is cosmopolitan, bustling and vibrant. There was also abject poverty.

“There was Lord Dunraven who was a massive landowner, but he was also exasperated with the New Yorkers because he was a sportsman and liked sailing yachts, and he thought the yanks had cheated the previous year. So he was going to New York to have a go at the yacht club.

“The people on the Cumbrae were going down to Birkenhead to perform there. But the interesting thing is that when they had this big dinner on the Germanic when it docked. Fred Bower recalls one of the characters he looked at was one who had a pullover of ‘Saved from the Sea’ on back to front. And if anything summed up what had just happened, it was that. They had all been saved from the sea. Whether it was good seamanship, luck or fortune, nobody drowned.”