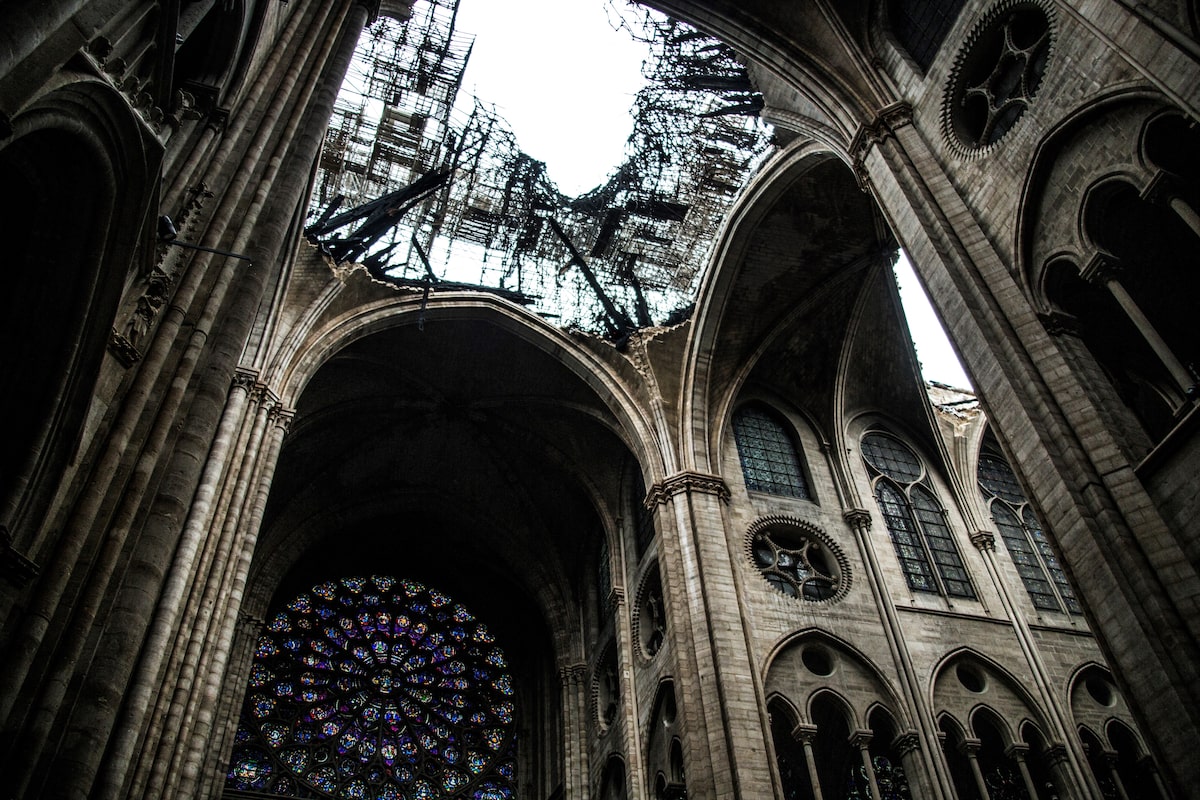

The damaged roof of Notre-Dame-de Paris Cathedral in Paris in April, 2019. The 12th-century cathedral has welcomed more than 11 million visitors since its reopening last year.AMAURY BLIN/AFP/Getty Images

Earlier this month, as Christmas decorations went up across the country, France marked the 120th anniversary of its 1905 law on the separation of church and state with countless ceremonies underscoring the sanctity of la laïcité in French society.

Under the 1905 law, whose principles are enshrined in France’s 1958 Constitution, the French state neither recognizes nor subsidizes any religion. Adopted after more than a century of brutal divisions between Catholic monarchists and anticlerical Republicans in post-revolutionary France, the law’s main effect at the time was to secularize an education system that had remained under the control of the Church.

The French right never fully endorsed the concept of la laïcité – as France’s particular brand of secularism is known – as it considers the country’s Christian heritage to be a fundamental characteristic of the French identity and worthy of protection. The official reopening last year of fire-ravaged Notre-Dame de Paris – which united a who’s-who of politicians and celebrities in the celebration of a Catholic mass – reminded everyone just how much the French value their Christian traditions, if not faith, when it suits them.

Nothing symbolizes France more than the 12th-century cathedral that has welcomed more than 11 million visitors since its reopening a year ago this month.

Konrad Yakabuski: France and Britain are in a fiscal mess. Can Canada avoid their fate?

Robyn Urback: Quebec shouldn’t ban street prayer. Municipalities should enforce existing laws

Each Christmas season, a handful of right-wing mayors still erect nativity scenes in municipal buildings, in contravention of the law, invariably sparking denunciations by left-wing politicians. Yet, while the French left never misses an opportunity to attack violations of the 1905 law by Christian mayors, it systematically rises up against efforts to enforce the law that target French Muslims.

And for the past three decades, the French state’s main focus, if not obsession, in upholding the 1905 law has been stopping the encroachment (real or perceived) of Islam in the public sphere. A debate that began in 1989, after three teenage girls were suspended for refusing to remove their hijabs at school, eventually resulted in a 2004 law that officially banned the wearing of conspicuous religious symbols in public schools.

That was followed by the adoption, in 2010, of a law banning the full-face veil in public. In the wake of the 2015 terrorist attacks and the 2020 assassination of a teacher who showed caricatures of the prophet Mohammed to his students, another law was passed in 2021 that empowers police to temporarily close mosques deemed to promote violence or hatred.

While la laïcité is officially about the neutrality of the French state, it increasingly appears to be most concerned with the religious emancipation of young French Muslims. After all, is this not what the ban on wearing religious symbols in public schools is really all about?

On the Dec. 9 anniversary of the 1905 law, French Education Minister Édouard Geffray told the National Assembly that two principles above all underscore la laïcité.

“The first is that, when a family entrusts its children to public school, it entrusts them so that they can grow free from all pressure and proselytism. That is not negotiable,” he said. “The second is that, when a teacher enters a classroom, he does not see Christian, Muslim, Jewish or atheist students; he sees children of the Republic. And when children enter a classroom, they do not see a Muslim, Jewish, Cristian or atheist teacher; they see a servant of the Republic. That is not negotiable.”

That is a neat principle, in theory, at least. It is another question altogether in practice.

The French education ministry keeps a tally of what it calls atteintes à la laïcité (violations of securalism) in public schools. It enumerated more than 1,300 in the first three months of the current school year alone. While Mr. Geffray boasted that this amounted a 10-per-cent decline from the same period in 2024, it also reflected the increasing generational division within French society over religious expressions in the public sphere.

A survey by the polling firm Ifop, marking the 120th anniversary of the 1905 law, found that while 67 per cent of French voters, and 85 per cent of those over 65, support banning religious symbols in the public sphere, this proportion falls to 46 per cent among 18- to 24-year-olds. While 52 per cent of those over 65 consider la laïcité to be an “essential” element of French identity, just 24 per cent of their younger counterparts agree. And the generational divide is growing.

Therein lies an irony: For a country that frowns on public manifestations of faith, French politics do seem to revolve an awful lot around religion. Fully 120 years after the official separation of church and state, France is still grappling with its meaning.