Last week, we left off with Judge Fitzpatrick’s November 17, 2025, memorandum, which detailed, among other serious concerns, newly appointed Lindsey Halligan’s misuse of materials seized from Daniel Richman by the FBI in 2016, 2017, and 2019. The problem, Fitzpatrick noted, was that those emails and messages not only contained privileged information—Richman had been James Comey’s attorney—but were seized during the “Midyear Exam” and “Arctic Haze” investigations. “Midyear” was the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) investigation into whether former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton had misused classified information when she set up her private email server, meant to determine whether there were violations of 18 U.S.C. § 641 (Theft and Conversion of Stolen Government Property) and 18 U.S.C. § 793 (Unlawful Gathering or Transmission of National Defense Information).

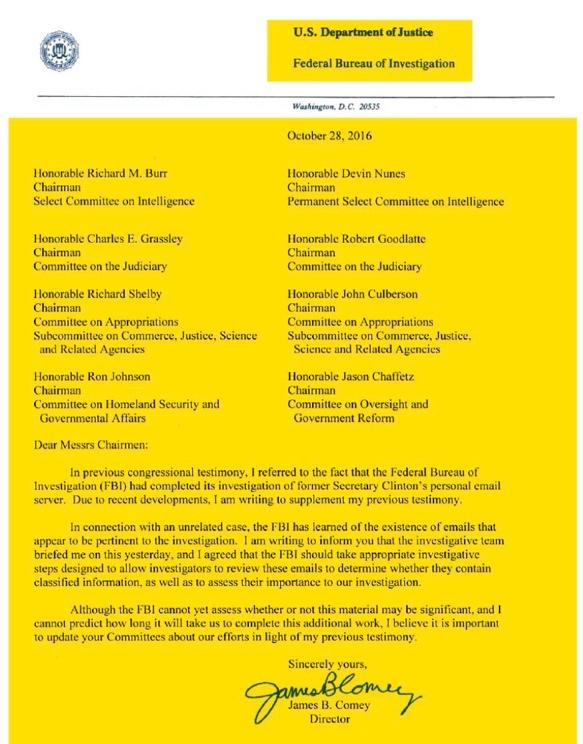

You may remember that when the FBI discovered a trove of material they had not seen before on the laptop of former U.S. Rep. Anthony Weiner—the estranged husband of Clinton’s senior campaign aide, Huma Abedin—Comey felt compelled to re-open the investigation and notify Congress.

And “Arctic Haze” was the FBI investigation into links between the 2016 Trump campaign and Russia.

FBI Director James Comey’s letter to Congress, Oct. 28, 2016. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

FBI Director James Comey’s letter to Congress, Oct. 28, 2016. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

Years later, Lindsey Halligan and the Department of Justice were using excerpts taken from Richman’s email account and computer hard drives to attempt to demonstrate very different crimes they claim James Comey committed.

With four presiding judges—three for Comey and one for Daniel Richman—and the government and defendants presenting completely different accounts of the facts, the story of the United States v. James Comey can be more than confusing. So, here is some recent history. On October 13, 2025, the DOJ belatedly asked Judge Nachmanoff—the lead judge in the Comey matter—to review the electronic evidence they had obtained from Daniel Richman in those earlier investigations. When the Comey team objected, Judge Nachmanoff decided that rather than rely on a possibly conflicted DOJ filter team to inspect attorney-client-privileged materials, he transferred that task to Judge Fitzpatrick. As Fitzpatrick clarified: “In this case, Mr. Comey seeks access to such materials in order to move for dismissal of the indictment based on alleged irregularities in the grand jury proceedings.”

Judge Fitzpatrick then had the responsibility of reviewing the complete transcript of Lindsey Halligan’s presentation to the grand jury she had convened and reading the testimony of Halligan’s one witness, “FBI Agent-3,” the very person the DOJ had tasked with reviewing those tainted materials for incriminating evidence against Comey. As a result, Fitzpatrick found multiple problems with the way the government had constructed its case:

The government’s decision to allow an agent who was exposed to potentially privileged information to testify before a grand jury is highly irregular and a radical departure from past DOJ practice … While it is true that the undersigned did not immediately recognize any overtly privileged communications, it is equally true that the materials seized from the Richman Warrants were the cornerstone of the government’s grand jury presentation. The government substantially relied on statements involving Mr. Comey and Mr. Richman in support of its proposed indictment. Agent-3 referred to these statements in response to multiple questions from the prosecutor and from grand jurors and did so shortly after being given a limited overview of privileged communications between the same parties …

[Emphasis added.]

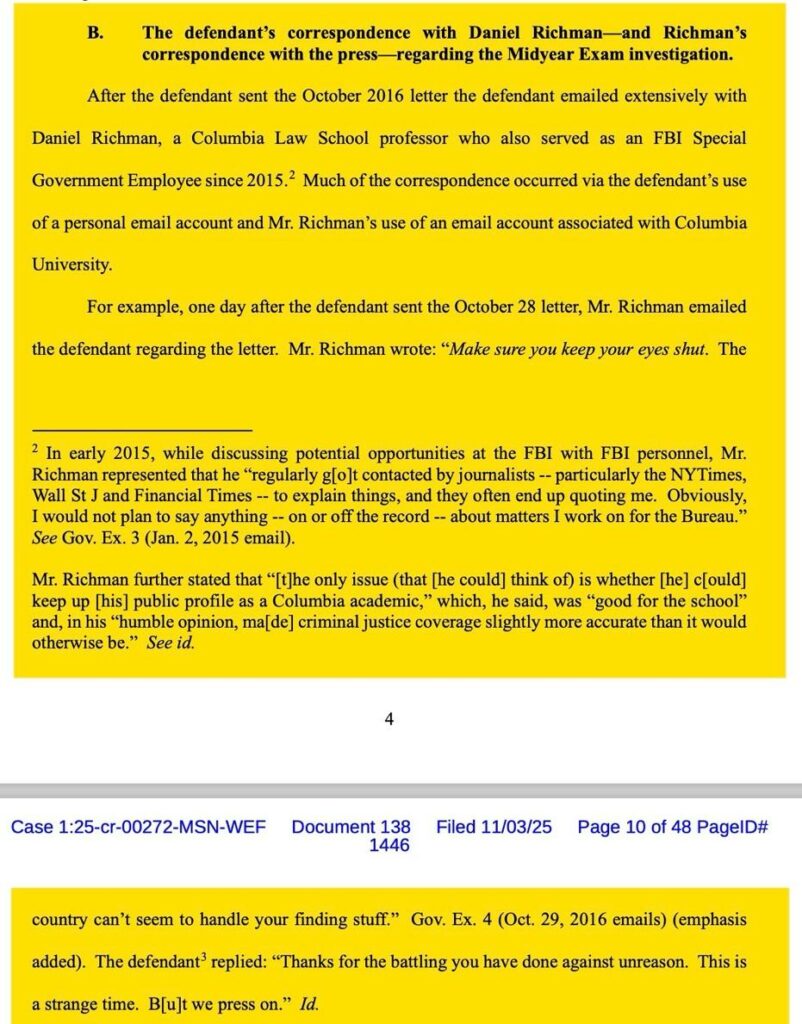

Here is an example from the DOJ’s November 3, 2025 “Response in Opposition to Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss Indictment Based on Vindictive and Selective Prosecution.” They offer an interchange between Richman and Comey, a conversation from eight years ago they imagine will impugn Comey:

U.S. response to defendant’s Motion to Dismiss, Vindictive Prosecution, Nov. 3, 2025. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

U.S. response to defendant’s Motion to Dismiss, Vindictive Prosecution, Nov. 3, 2025. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

To put this interchange in context, it is important to remember how extraordinarily controversial Comey’s decision was to inform Congress and the public that the FBI needed to reopen the investigation into Hillary Clinton. It makes perfect sense that Comey and Richman’s conversations touched on how best to communicate those complex and competing issues to the public.

The government continued:

The next day, Mr. Richman sent the defendant an email regarding an op-ed he had been asked to write for The New York Times about the defendant’s letter … Mr. Richman stated that he was ‘not inclined’ to ‘write something,’ but that he would ‘do it’ if the defendant thought it would ‘help things to explain that [the defendant] owed cong absolute candor,’ and that the defendant’s ‘credibility w cong w[ould] be particularly important in the coming years of threatened cong investigations.’ … The defendant responded: ‘No need. At this point it would [be] shouting into the wind. Some day they will figure it out. And as [Individual 1 and Individual 2] point out, my decision will be one a president elect Clinton will be very grateful for (although that wasn’t why I did it).’ …

The defendant appears to have reconsidered that view shortly thereafter. On November 1, 2016, he emailed Mr. Richman, stating:

When I read the times coverage involving [Reporter 1], I am left with the sense that they don’t understand the significance of my having spoke about the case in July. It changes the entire analysis. Perhaps you can make him smarter.

Let’s imagine the Times had a policy against writing new articles close to elections if the articles might influence the election. Consistent with that policy they would avoid writing this week if sources told them that the FBI was looking at Huma Abedin’s emails.

But let’s imagine that they wrote a very high profile piece in July that sources lead them to now conclude was materially inaccurate. Would they correct it or stay silent because they have a policy to avoid action near elections?

I suspect they would quickly conclude that either course is an ‘action’ and the choices are either reporting or concealing but there is no longer a ‘neutral’ option because of the reporting in July. I also suspect they would resolve very quickly to choose the action of disclosing because to remain silent is to actively mislead, which has a wide range of very bad consequences.

Why is this so hard for them to grasp? All the stuff about how we were allegedly careful not to take actions on cases involving other allegations about which we have never spoken is irrelevant. I love our practice of being inactive near elections. But inactivity was not an option here. The choices were act to reveal or act to conceal.

See Gov. Ex. 6 (Nov. 1–2, 2016 emails) (emphasis added).

Halligan then cites the exceptionally confusing questioning of Comey by Sen. Chuck Grassley (R – Iowa) in 2017 and Sen. Ted Cruz’s (R – Texas) equally confusing resurrection of that conversation in 2020 to prove that Comey lied to them both about leaking sensitive information. Somehow, the government imagines that these Comey-Richman conversations are evidence of guilt. But clearly the two of them were discussing the implications of Comey’s controversial decision to inform Congress of the FBI’s new discovery and the continuing commitment of the FBI to find the full truth. That Comey expressed to Richman his belief that Hillary Clinton would eventually appreciate his decision to go public is really just evidence of his naïvete, imagining she would understand his commitment to candor and transparency and his decision to place official duty above political expedience. That Comey imagined she would be president-elect was no different than the predictions of so very many Americans at that time.

In her Motion to Dismiss, Halligan then states:

The societal interests in this prosecution are readily apparent and overwhelming. The defendant is a former FBI Director who lied to Congress about his conduct while at the helm of the Nation’s primary federal law-enforcement agency. His prosecution implicates societal interests of the highest order. Nonetheless, he asks the Court to take the extraordinary step of dismissing his indictment because—he says—he is being vindictively and selectively prosecuted. Given the deep-seated separation-of-powers principles at stake, his request can be granted only if ‘the Constitution requires it.’ See United States v. Olvis, 97 F.3d 739, 743 (4th Cir. 1996). It doesn’t. Therefore, ‘judicial intervention should not deny the community the benefit of a prosecution.’ See United States v. Wilson, 262 F.3d 305, 317 (4th Cir. 2001).

Halligan arrogantly asserts that society shares her belief that the claims and purpose of prosecuting Comey are “readily apparent and overwhelming.” So, it is important to point out that many attorneys in the Eastern District of Virginia thought their chances of convicting Comey were slim, then especially weaker when, in response to a subpoena, Daniel Richman testified under oath that Comey never asked him to release the memos he drafted of his conversations with President Trump. And Comey never suggested that he share classified material.

There seems to be an unfortunate connection between the over-heated, rhetorical claims of Bondi and Halligan and their lack of willingness to play by the accepted rules of legal procedure, to actially prove their cases beyond a reasonable doubt. The result is a growing conflict between those career DOJ prosecutors with long-standing experience working for a variety of administrations and these new Trump appointees focused on serving the political whims of their boss. In the Comey case, the DOJ has relied on the constitutionally suspect use of materials seized for one purpose in 2016–17, now brought to bear in 2025 to prove yet another completely different set of offenses.

It may seem as if I am belaboring this point, but the behavior Fitzpatrick highlights is being repeated by the DOJ in case after case. As The Washington Post most recently points out, there is a new Donald Trump-sparked order to have his DOJ focus on “leftist” news outlets and political activism. And it is not hard to predict that we are sure to see even more distorted prosecutions based on suspect evidence.

Meanwhile, having now reviewed the materials Halligan has relied on, Judge Fitzpatrick notes:

The record reflects that in 2019 and 2020, the government took modest–and as it turned out ineffective–steps to identify and isolate potentially privileged information contained in the materials seized pursuant to the Richman Warrants … However, the government never engaged Mr. Comey in this process even though it knew that Mr. Richman represented Mr. Comey as his attorney as of May 9, 2017, and three of the four Richman Warrants authorized the government to search Mr. Richman’s devices through May 30, 2017, 21 days after an attorney-client relationship had been formed …

At the time the Richman Warrants were executed, the government was aware not only that Mr. Richman represented Mr. Comey, but also that he maintained ongoing attorney-client relationships with other individuals … As a result, when the government obtained the first Richman Warrant in 2019, it was clearly foreseeable that Mr. Richman’s devices contained potentially privileged communications with numerous third parties, including Mr. Comey. Nevertheless, in 2019 and 2020, the government made a conscious decision to exclude Mr. Comey from the filter process, even though Mr. Comey, as the client, is the privilege holder, not Mr. Richman …

Here, the government was permitted to search all of the Richman materials but authorized to seize only evidence related to violations of 18 U.S.C. § 641 (Theft and Conversion of Stolen Government Property) and 18 U.S.C. § 793 (Unlawful Gathering or Transmission of National Defense Information), both markedly different offenses than those with which Mr. Comey is currently charged …

By the summer of 2025, the FBI and the United States Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Virginia (USAO-EDVA) had initiated a criminal investigation into Mr. Comey … As part of the investigation, on September 12, 2025, an FBI agent assigned to the Director’s Advisory Team was instructed, apparently with the concurrence of the USAO-EDVA, to review ‘a Blu-ray disc that contained a full Cellebrite extraction and Reader reports of [Mr. Richman’s] iPhone and iPad backups.’ … Inexplicably, the government elected not to seek a new warrant for the 2025 search, even though the 2025 investigation was focused on a different person, was exploring a fundamentally different legal theory, and was predicated on an entirely different set of criminal offenses. The Court recognizes that a failure to seek a new warrant under these circumstances is highly unusual …

The government presented this case to the grand jury on September 25, 2025 … The same day, prior to the grand jury presentment … Agent-3, rather than remove himself from the investigative team until the taint issue was resolved, proceeded into the grand jury undeterred and testified in support of the pending indictment. In fact, Agent-3 was the only witness to testify before the grand jury in support of the pending indictment. Id. The government’s decision to allow an agent who was exposed to potentially privileged information to testify before a grand jury is highly irregular and a radical departure from past DOJ practice.

[Emphasis added.]

Judge Fitzpatrick then cites two significant errors Halligan made in her presentation to the jury. What is crystal clear is that the attorney general, in her zeal to do the bidding of Donald Trump, has enabled an incompetent prosecutor to join her in repeatedly ignoring constitutional imperatives. Together, they are practicing sub-standard law before increasingly frustrated federal judges. And rather than correct that behavior, they double-down by sacrificing competence for political correctness.

Now, while Fitzpatrick was focused on investigating and ruling on the government’s use of privileged material, Senior United States District Judge Cameron McGowan Currie is at work in South Carolina at the request of Judge Nachmanoff. As she explains in her order and opinion:

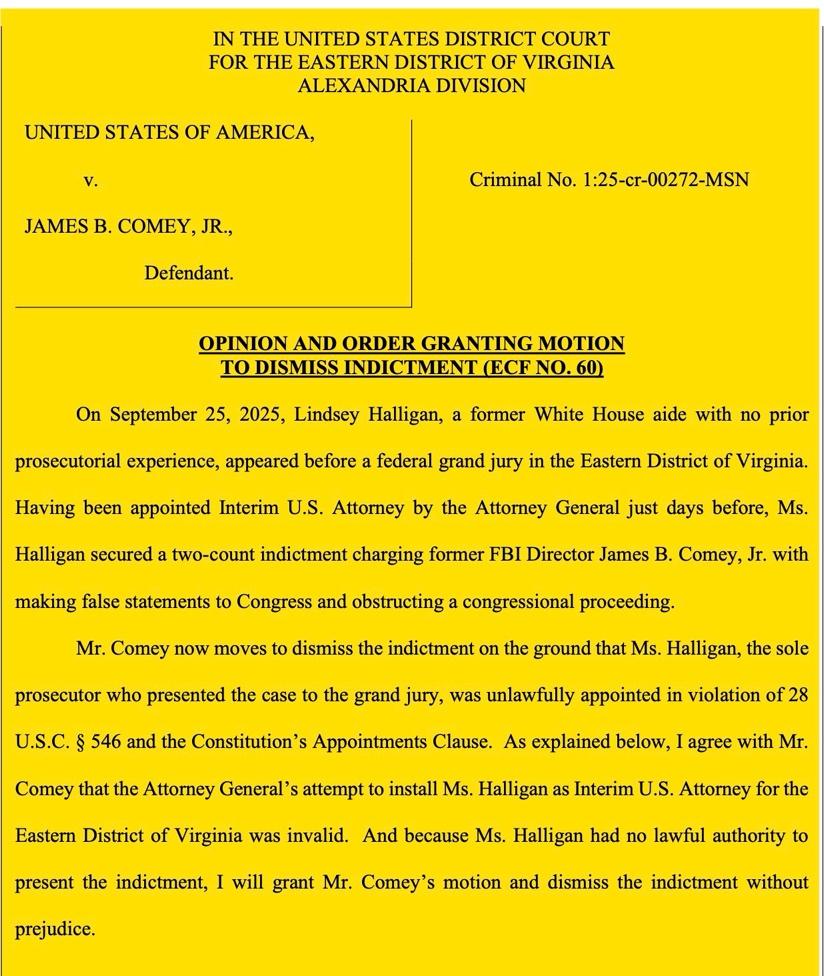

On September 25, 2025, a grand jury sitting in the Eastern District of Virginia returned a two-count indictment against Mr. Comey, charging him with making false statements within the jurisdiction of the legislative branch, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1001(a)(2), and obstructing congressional proceeding, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1505. ECF No. 1. The charges stem from testimony Mr. Comey gave during a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing in 2020. Ms. Halligan was the only prosecutor who participated in the Government’s presentation to the grand jury, and only her signature appears on Mr. Comey’s indictment. ECF No. 1 at 2.11.

On October 20, 2025, Mr. Comey moved to dismiss the indictment on the ground that Ms. Halligan’s appointment was unlawful under section 546 and violated the Appointments Clause … On October 21, the Chief Judge of the Fourth Circuit designated me to consider this and any other motion ‘concerning the appointment, qualification, or disqualification of the United States Attorney or the United States Attorney’s Office’ in the Eastern District of Virginia …

Finding it ‘necessary to determine the extent of [Ms. Halligan’s] involvement in the grand jury proceedings,’ I ordered the Government on October 28 to submit for in camera review ‘all documents relating to [Ms. Halligan’s] participation’ before the grand jury, ‘along with complete grand jury transcripts.’ … Upon reviewing the transcript provided by the Government, I determined it did not include any remarks made by Ms. Halligan ‘before and after the testimony of the sole witness.’ … Accordingly, on November 4, I directed the Government to submit ‘a complete [t]ranscript and/or recording of all statements made by [Ms. Halligan] to the grand jury on September 25, 2025.” … In a notice of compliance filed on November 5, the Government represented it had produced all materials requested by the October 28 and November 4 orders:

In response [to the October 28 order], the government provided the transcript of the Grand Jury proceedings that was previously provided to the government by the transcription service. …

Further, the government requested that the transcription service transcribe the entire recording, which had not been done previously. This new transcript was provided to the government on November 5, 2025. The above items have now been provided to the Court in compliance with the Court’s Orders.

On November 3, the Government responded in opposition to Mr. Comey’s motion … Also that day, the Government filed an order from the Attorney General dated October 31, 2025 … The October 31 Order reads in its entirety:

On September 22, 2025, I exercised the authority vested in the Attorney General by 28 U.S.C. § 546 to designate and appoint Lindsey Halligan as the United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia. See Att’y Gen. Order No. 6402-2025. For the avoidance of doubt as to the validity of that appointment, and by virtue of the authority vested in the Attorney General by law, including 28 U.S.C. §[§] 509, 510, and 515, I hereby appoint Ms. Halligan to the additional position of Special Attorney, as of September 22, 2025, and thereby ratify her employment as an attorney of the Department of Justice from that date going forward. As Special Attorney, Ms. Halligan has authority to conduct, in the Eastern District of Virginia, any kind of legal proceeding, civil or criminal, including grand jury proceedings and proceedings before United States Magistrates and Judges. In the alternative, should a court conclude that Ms. Halligan’s authority as Special Attorney is limited to particular matters, I hereby delegate to Ms. Halligan authority as Special Attorney to conduct and supervise the prosecutions in United States v. Comey (Case No. 1:25-CR-00272) and United States v. James (Case No. 2:25-CR-00122).

In addition, based on my review of the grand jury proceedings in United States v. Comey and United States v. James, I hereby exercise the authority vested in the Attorney General by law, including 28 U.S.C. §[§] 509, 510, and 518(b), to ratify Ms. Halligan’s actions before the grand jury and her signature on the indictments returned by the grand jury in each case.

[Emphasis added.]

Judge Cameron McGowan Currie continues:

Mr. Comey filed his reply on November 10 … On November 13, I heard oral argument from the parties and took the matter under advisement … During the hearing, I raised concerns about the Attorney General’s ability to review Ms. Halligan’s presentation to the grand jury when, as of October 31, the Government had not yet received the complete transcript of the proceeding. ECF No. 189 at 36–37. I also noted that, based on my in camera review, there appeared to be a gap in the grand jury transcript from 4:28 p.m. to 6:47 p.m., when the indictment was returned to the magistrate judge …

Nevertheless, the government once again claimed that the transcript was complete and argued that the time when Halligan was not present was spent in grand jury deliberations. According to CNN, it was not until November 19, 2025, that Halligan admitted on the witness stand that once the jury had voted against one charge of three, she never took the time to rewrite a new indictment for two counts and, therefore, never took the time to present that to grand jury for their approval. So, in fact, the entire grand jury had not seen the new, completely rewritten Comey indictment.

Judge Currie then details her examination of the actual text of the legislation governing the appointment of interim U.S. attorneys and its legislative history. She writes:

In sum, the text, structure, and history of section 546 point to one conclusion: the Attorney General’s authority to appoint an interim U.S. Attorney lasts for a total of 120 days from the date she first invokes section 546 after the departure of a Senate-confirmed U.S. Attorney. If the position remains vacant at the end of the 120-day period, the exclusive authority to make further interim appointments under the statute shifts to the district court, where it remains until the President’s nominee is confirmed by the Senate.

Ms. Halligan was not appointed in a manner consistent with this framework. The 120-day clock began running with Mr. Siebert’s appointment on January 21, 2025. When that clock expired on May 21, 2025, so too did the Attorney General’s appointment authority. Consequently, I conclude that the Attorney General’s attempt to install Ms. Halligan as Interim U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia was invalid and that Ms. Halligan has been unlawfully serving in that role since September 22, 2025. …

Because Ms. Halligan was appointed in violation of that scheme, her appointment was not authorized “by Law” and thus also violates the Appointments Clause …

Mr. Comey contends Ms. Halligan’s unlawful appointment renders all her purported official actions void ab initio … He therefore argues the case must be dismissed because Ms. Halligan was not lawfully exercising executive power when she appeared before the grand jury alone and obtained his indictment … I agree.

[Emphasis added.]

Judge Currie’s order dismissing the indictment of Comey, Nov. 24, 2025. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

Judge Currie’s order dismissing the indictment of Comey, Nov. 24, 2025. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

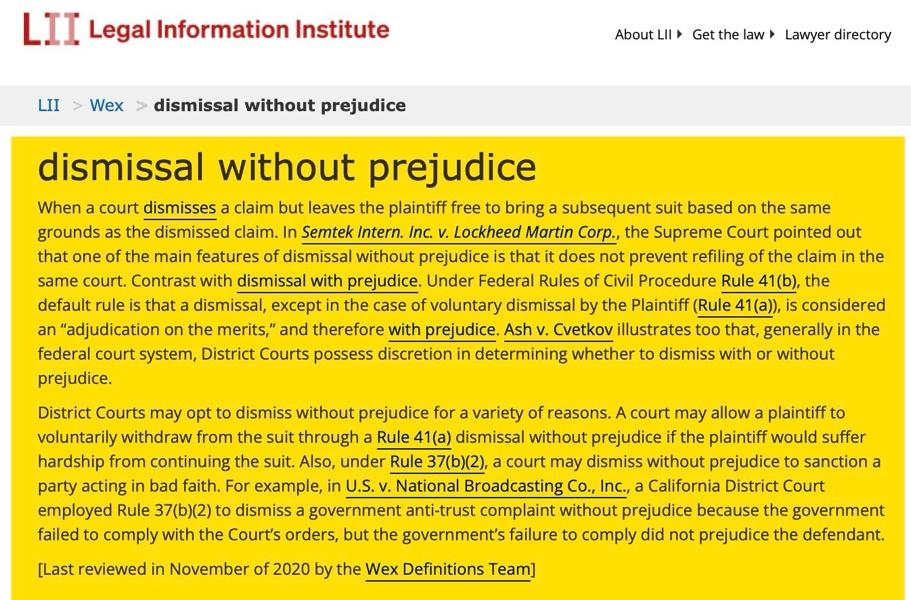

I defer to the Cornell Law School to explain the ramifications of Judge Currie’s decision to dismiss the case without prejudice:

Cornell Law Library’s definition of “dismissal without prejudice.” Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

Cornell Law Library’s definition of “dismissal without prejudice.” Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

Not surprisingly—but shocking nonetheless—the Department of Justice decided to reinterpret Judge Currie’s disqualification of Lindsey Halligan:

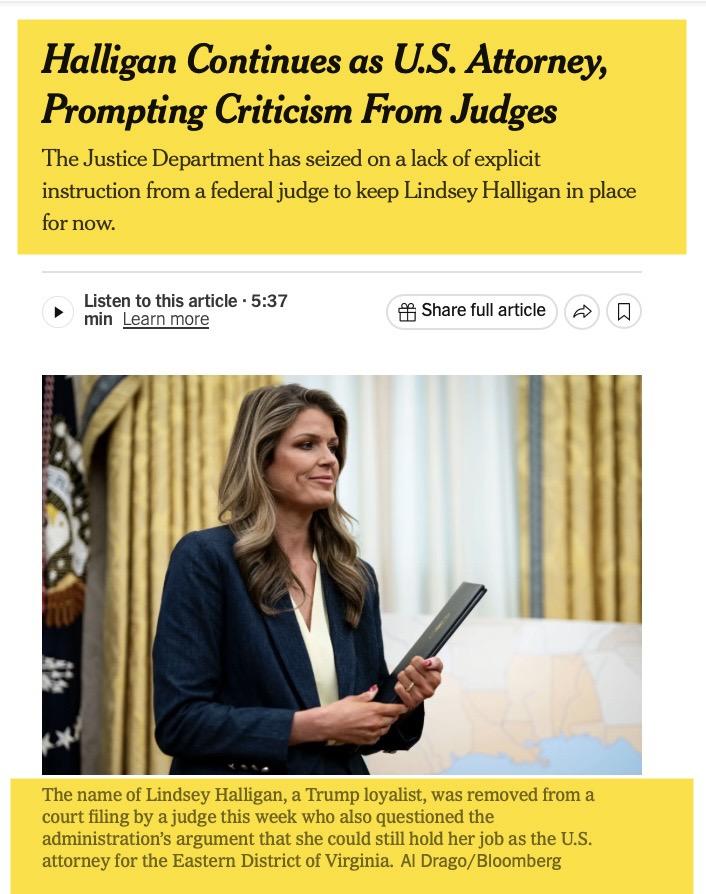

The New York Times, Dec. 5, 2025. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

The New York Times, Dec. 5, 2025. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

The New York Times reported:

The legal decision that ended the criminal cases against the former F.B.I. director James B. Comey and New York’s attorney general, Letitia James, has left the leadership of a key U.S. attorney’s office in Virginia in limbo, leading to frustration among judges in the state.

A federal judge ruled last week that the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, Lindsey Halligan, a Trump loyalist, had been unlawfully appointed as the U.S. attorney by the Trump administration. As a result, the judge ordered the dismissal of the high-profile indictments against Mr. Comey and Ms. James.

But while that decision, by Judge Cameron McGowan Currie, who was brought in from a district in South Carolina to handle the question, found Ms. Halligan’s appointment invalid, it did not expressly order her removed from the office.

The Justice Department has seized on the lack of explicit instruction to keep Ms. Halligan in place for now, eliciting the judges’ irritation …

[Emphasis added.]

Meanwhile, as CNN reports, several judges expressed their annoyance that the Department of Justice continued to act as if Lindsey Halligan was the legal attorney general for the Eastern District of Virginia:

CNN, Dec. 5, 2025. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

CNN, Dec. 5, 2025. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

CNN explains:

Federal judges in Alexandria, Virginia, have lashed out at the Justice Department as they continue to list Lindsey Halligan on court documents — some going as far as striking her name from paperwork from the bench.

Two magistrate judges and a district court judge in Alexandria, Virginia, told prosecutors in open court they didn’t believe Halligan’s name should be on new criminal case filings, such as guilty plea documents and indictments, after a decision in the district last week said she is not the US Attorney.

One of those judges, Magistrate William Fitzpatrick, said at a criminal case hearing Tuesday that filing criminal charging papers ‘under Ms. Halligan’s name’ at this time ‘is simply not acceptable,’ according to a transcript obtained by CNN.

Both Fitzpatrick and another judge in the district, Michael Nachmanoff, told prosecutors this week they believed the ruling was clear that Halligan wasn’t the US attorney for all cases. They both noted, in separate hearings this week, according to court transcripts, that the Justice Department hadn’t appealed the ruling about Halligan, nor asked any court to pause it for a possible appeal.

‘The law in this district right now is that she is not and has not been the United States Attorney,’ Fitzpatrick said on Tuesday. …

Nachmanoff, who oversaw the Comey case at the trial level, decided in a separate hearing Thursday for a Honduran man illegally in the US that Halligan’s name would need to be struck from that man’s case records.

He said he was finding it ‘difficult to reconcile’ the court opinion with what the Justice Department is doing now, according to a transcript of the hearing Thursday. …

During other criminal hearings on Tuesday, Fitzpatrick told a prosecutor that he would be striking Halligan’s name from criminal court documents, while another judge, Magistrate Lindsey Vaala, said she would annotate new indictments to acknowledge the ruling on Halligan.

The exchanges, captured on official audio recordings of the hearings and obtained first by CNN, emphasize a continued lack of formal explanation from Justice Department headquarters about why it believes Halligan can remain in the job.

‘I agree with you that it is peculiar and we are in unusual territory,’ Vaala told a different prosecutor later that afternoon, as she received newly approved indictments from prosecutors and the grand jury. She said ‘the concern’ is accepting an indictment that has a signature block inconsistent with the previous judge’s decision.

[Emphasis added.]

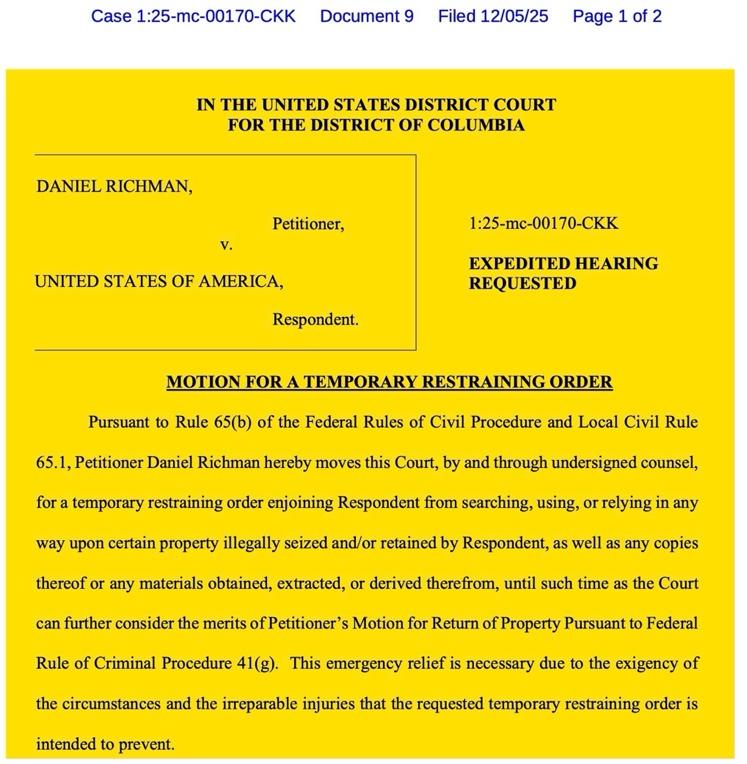

Meanwhile, as Anna Bower of Lawfare reported, Daniel Richman filed suit against the United States seeking to prevent the government from looking through and using any of the material they seized from him in 2016 and 2017.

Daniel Richman v. United States of America, Motion for Temporary Restraining Order, Dec. 5, 2025. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

Daniel Richman v. United States of America, Motion for Temporary Restraining Order, Dec. 5, 2025. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

In his memorandum of law in support of his motion, Richman writes:

This motion seeks redress for the government’s violations of Petitioner Daniel Richman’s Fourth Amendment rights. Between 2017 and 2020, Professor Richman, an attorney and law professor with a distinguished record of government service, had various interactions with the government relating to his legal representation of former FBI Director James B. Comey, Mr. Comey’s handling of potentially classified information, and related communications with the media. Professor Richman agreed to allow the government to image his personal computer for the purpose of identifying and deleting certain sensitive documents and subsequently agreed to a limited search of the image. The government later obtained four warrants that authorized additional searches of the image and of Professor Richman’s email and iCloud accounts. Professor Richman was never charged with a crime and had no contact with the government regarding these matters between 2021 and 2025.

On September 25, 2025, Mr. Comey was indicted in the Eastern District of Virginia. Before the indictment against Mr. Comey was dismissed, disclosures in the case brought to light troubling facts concerning the government’s handling of the materials it obtained from Professor Richman between 2017 and 2020. First, the government violated the warrants that authorized its searches of Professor Richman’s files by apparently failing to identify and segregate responsive materials, thus seizing the entirety of the searched materials. Second, despite having no need for those materials after 2021 when its investigation closed, the government nonetheless retained the materials that it collected from Professor Richman’s personal computer, email, and iCloud account. Finally, and perhaps most egregiously, in a last-ditch effort to support its prosecution of Mr. Comey, the government conducted a new warrantless search of Professor Richman’s files in September 2025 in contravention of clear constitutional rules and the attorney-client privilege.

[Emphasis added.]

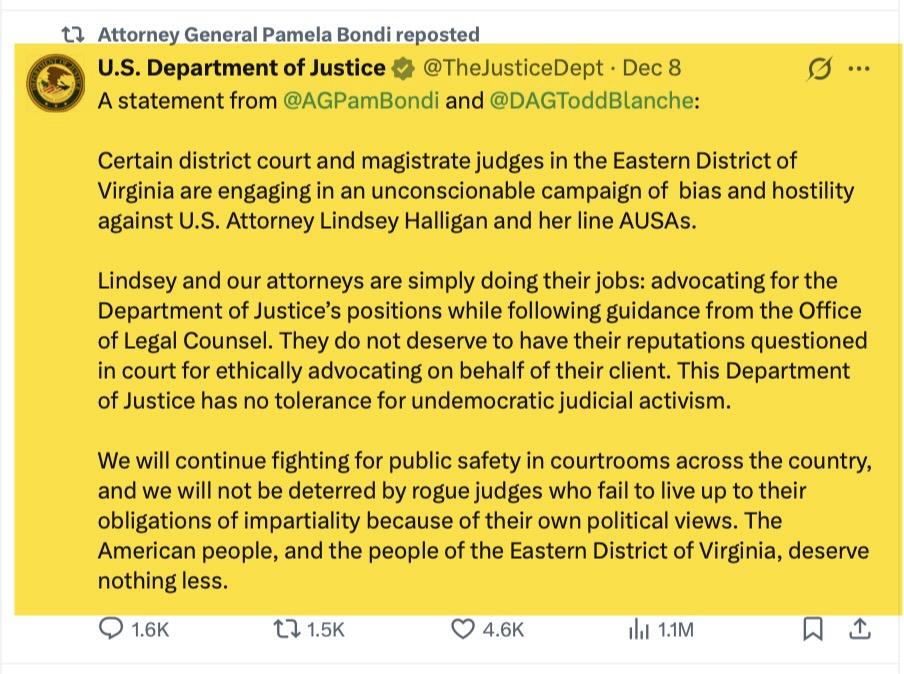

Meanwhile, the combination of Judge Curri’s ruling, the very public annoyance of district court judges that Halligan’s name still appeared on court documents, and Daniel Richman’s lawsuit seemed to short-circuit Attorney General Pam Bondi. She could not help but attack:

The Department of Justice posts a statement from Attorney General Pam Bondi on X, Dec. 8, 2025. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

The Department of Justice posts a statement from Attorney General Pam Bondi on X, Dec. 8, 2025. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

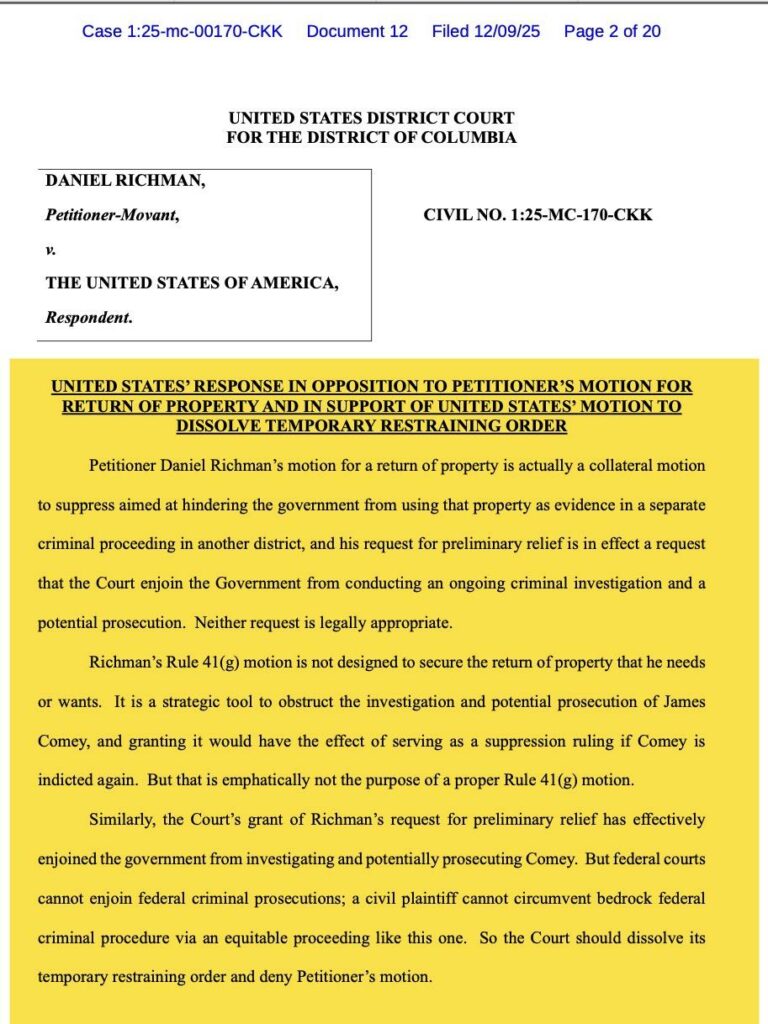

The attack continued the next day with the government’s official response to Daniel Richman’s lawsuit.

United States’ response in opposition to Richman’s Motion for Return of Property. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

United States’ response in opposition to Richman’s Motion for Return of Property. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

What is remarkable about Todd Blanche and Lindsey Halligan’s filing is their total disrespect and contempt for the legal arguments posed by Richman. The government takes no responsibility for not seeking an updated warrant to maintain possession and use the materials they seized during 2016 and 2017. They take no responsibility for the fact that they directed an FBI agent to rummage through files that may well have contained privileged material to find what they hoped was compromising evidence for an entirely new set of crimes. And then they had that agent testify to the grand jury.

Instead, they diminish the legitimate claims of Daniel Richman that his Fourth Amendment rights were violated:

… it is clear that Richman’s Rule 41(g) motion is not a valid or meritorious motion for return of property, but instead a transparent effort to suppress evidence in the Comey matter. That is improper multiple times over, and so the Court should deny the motion and dissolve the TRO that it issued on an ex parte basis last week [sic]

… His request for ‘copies of the seized documents’ and ‘an order directing the government to cease inspecting the evidence pending a ruling,’ confirms that his motion seeks suppression of evidence, not the return of property.

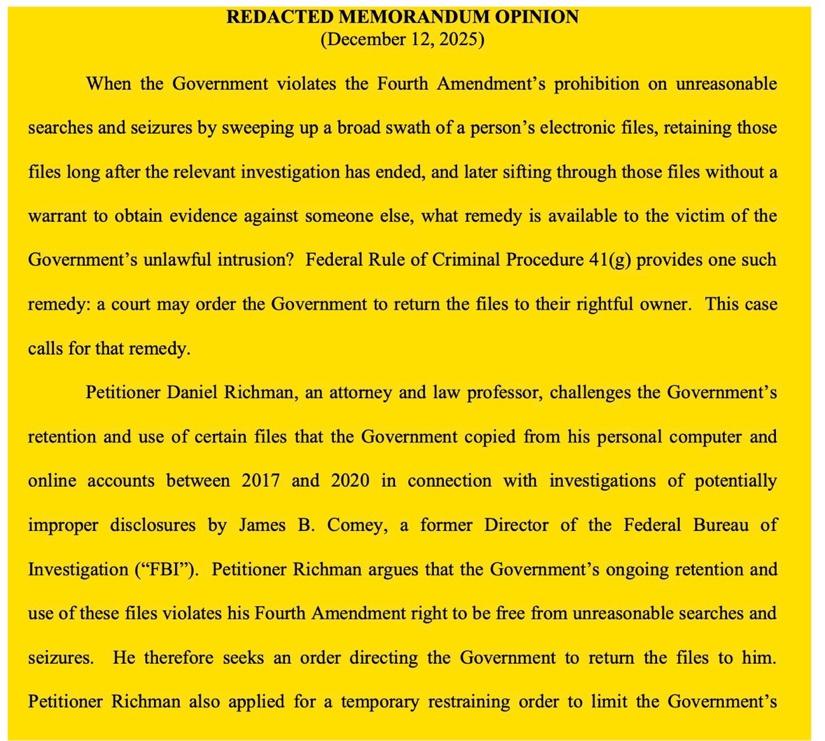

On December 12, 2025, Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly filed her memorandum opinion in the Richman case.

Daniel Richman v, U.S., Redacted Memorandum Opinion, Dec. 12, 2025. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

Daniel Richman v, U.S., Redacted Memorandum Opinion, Dec. 12, 2025. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

Relying on the protections of the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution, Judge Kollar-Kotelly made a simple and clear case:

When the Government violates the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition on unreasonable searches and seizures by sweeping up a broad swath of a person’s electronic files, retaining those files long after the relevant investigation has ended, and later sifting through those files without a warrant to obtain evidence against someone else, what remedy is available to the victim of the Government’s unlawful intrusion? Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 41(g) provides one such remedy: a court may order the Government to return the files to their rightful owner. This case calls for that remedy.

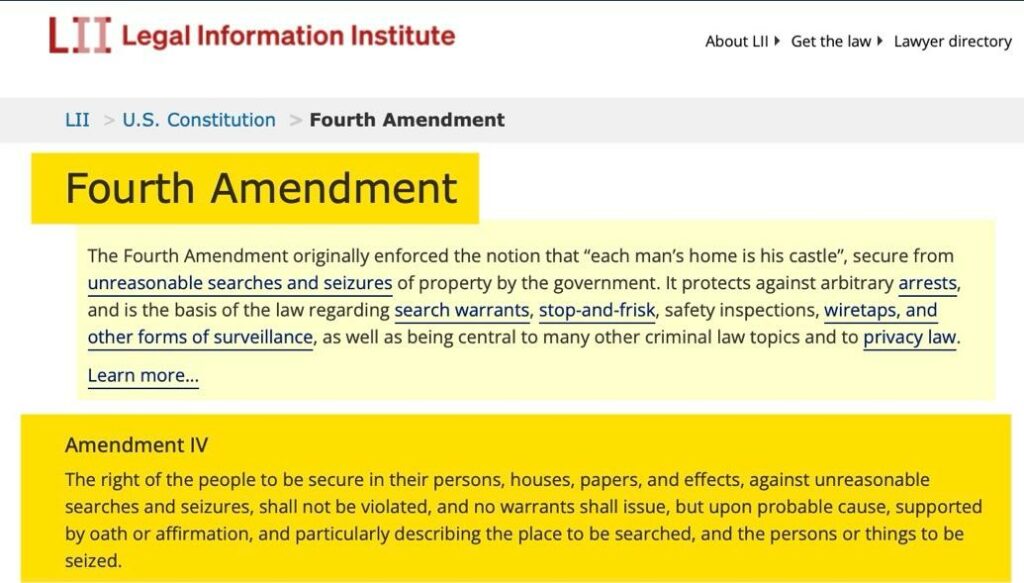

Just to remind you, here is the text of the Fourth Amendment:

Fourth Amendment to the Constitution. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

Fourth Amendment to the Constitution. Used under Fair Use provisions of U.S. Copyright Law. Highlighting added.

Judge Kollar-Kotelly offers a balance opinion, focusing on addressing the Fourth Amendment harms experienced by Richman but attempting not to restrict the government from future legal uses of the material:

For two reasons, this Court concludes that although Petitioner Richman is entitled to the return of the improperly seized and searched materials at issue here, he is not entitled to an order preventing the Government from ‘using or relying on’ those materials in a separate investigation or proceeding, as long as they are obtained through a valid warrant and judicial order …

When fashioning a prospective equitable remedy for these harms, this Court must take care to ensure that any injunction is not ‘broader than necessary to provide complete relief to each plaintiff with standing to sue.’ … Here, Petitioner Richman has established an ongoing constitutional injury to his right to be free from unreasonable seizures, as well as cognizable ongoing harms to his compelling interest in the privacy of his personal and professional communications. An order requiring the Government to return all copies of the covered materials to him substantially redresses these specific injuries … By contrast, a broader order barring the Government from relying on the image in other ways—for example, by pursuing investigative leads against other people because of information found in the image before its return—would not substantially mitigate Petitioner Richman’s own injuries …

Second, binding precedent precludes this Court from preventing the use of evidence in a future criminal prosecution of any person other than Petitioner Richman … Under these controlling precedents, this Court concludes that Petitioner Richman is not entitled to an order that directly limits the use of the evidence at issue in a criminal prosecution of another person ….

Specifically, the Court shall allow the Government, before returning the materials at issue to Petitioner Richman, to create one complete electronic copy of those materials and deposit that copy, under seal, with the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, for future access pursuant to a lawful search warrant and judicial order. The U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, which shall have supervisory authority over access to this material, may then exercise its discretion in evaluating any future application for a warrant, including deciding whether to allow Petitioner Richman an opportunity to move to quash any such warrant before it is executed.

Even though Judge Kollar-Kotelly had done her best to strike a compromise between Richman’s Fourth Amendment rights and the possible need of the government, with a properly secured warrant, to investigate and prosecute additional criminal behavior, the Justice Department still was not willing to cooperate. On December 15, 2025, they filed a motion to modify her order, questioning and quibbling with what she required of them and making claims that some of the material properly belonged to the government and not Richman:

The Government is simultaneously complying with a litigation hold put in place pursuant to a preservation letter from counsel for James Comey … The Government further understands that copies of portions of the relevant files are in the possession of government personnel (e.g., having been printed, saved locally, or emailed). Finally, the Government understands that the relevant files may include e-mails and other electronic communications between Petitioner Richman and James Comey, when both individuals were employed at the FBI, and regarding government business. Such files are undoubtedly property of the Government and are likewise required to be maintained by the Government, and in the Government’s possession, pursuant to the Federal Records Act of 1950.

From the very beginning, the Department of Justice has been a loyal soldier in Donald Trump’s War of Revenge and Retribution. Finally, someone inside the inner circle, Chief of Staff Susan Wiles, could not help admit the truth. In a multi-part interview with Vanity Fair, Chris Whipple asked Wiles about the Comey indictment:

In November, it was Comey’s turn in the dock. ‘So tell me why the Comey prosecution doesn’t just look like the fix is in,’ I asked her.

‘I mean, people could think it does look vindictive. I can’t tell you why you shouldn’t think that.’ Wiles said of Trump: ‘I don’t think he wakes up thinking about retribution. But when there’s an opportunity, he will go for it.’

He is not the only one to opt for retribution. First off, Attorney General Pam Bondi took a hatchet to the staff at the Eastern District of Virginia, pushing out anyone with experience and integrity. Then Bondi facilitated Donald Trump’s stupid decision to install one of his least competent personal attorneys, Lindsey Halligan, to prosecute two of his favorite enemies: Letitia James and James Comey. To the surprise of no one who knows, Lindsey Halligan created a case out of virtually nothing, then did a miserable job of presenting that almost nonexistent case to a grand jury. Along the way, she neglected to present her revised indictment to the full grand jury and mischaracterized the responsibilities of the prosecution and added unconstitutional responsibilities to the defense. Then Halligan told the grand jury they should not worry if her case was not convincing enough—they would provide more evidence later on at trial.

Four judges have weighed in to protect our Constitution and the rule of law. For the moment, James Comey is safe. But Donald Trump’s desire for revenge seems without limit. So don’t be surprised if he and his minions try once more to go for it.