To grasp the full complexity of how our planet works, a team of German scientists has built something extraordinary: an ultra-detailed digital twin of Earth. This groundbreaking simulation could transform how researchers study the planet’s evolving climate.

For decades, scientists have relied on computer models to reconstruct Earth’s past and predict its future. Using vast amounts of atmospheric and environmental data, they simulate how weather patterns and climate systems behave over time. But the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Germany has now taken that technology to a new level, creating a next-generation Earth model with a resolution of just 1.25 kilometers.

This virtual Earth is made up of 672 million cells — 336 million representing land and ocean surfaces, and another 336 million modeling the atmosphere. Each cell is designed to simulate two key processes:

• A “fast” system covering meteorology — water, wind, and energy. By using the advanced ICON (ICOsahedral Nonhydrostatic) model, researchers can now capture extremely local weather events in unprecedented detail.

• A “slow” system representing climatology — including the carbon cycle, the biosphere’s evolution, and ocean geochemistry.

By combining the results from these fast and slow systems, the new simulation achieves a resolution 40 times finer than any previous model — an enormous leap forward in climate science.

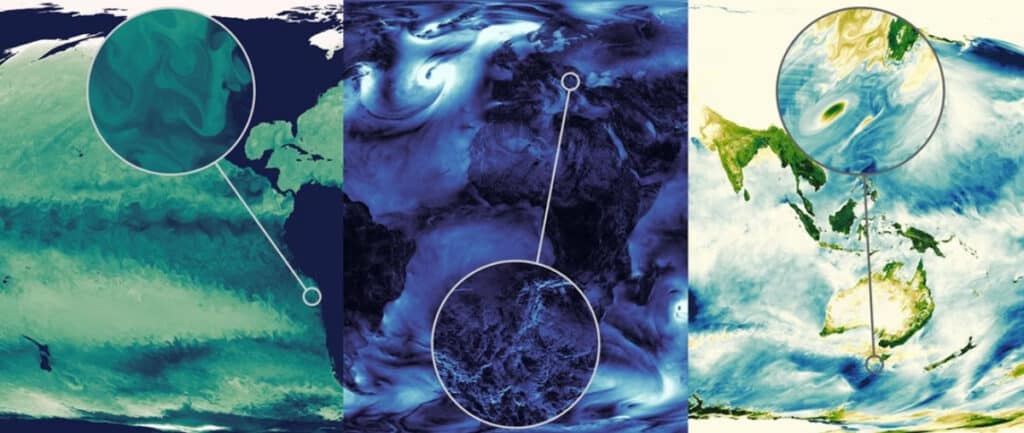

Three images showing the results of the ultra-precise computer simulation: on the left, phytoplankton in the ocean near Chile; in the middle, winds over the Balkan mountains; and on the right, carbon exchange between land and ocean near Tasmania. @ Max Planck Institute

A clearer picture of Europe’s climate future

Why does this matter? Because everything on Earth is connected — the land, the oceans, the atmosphere, and all living systems. When one component changes, it triggers ripple effects across the planet, from local ecosystems to global weather patterns. Earth is, in many ways, a single living system, and we’re only beginning to understand its intricate web of interactions.

The new simulation allows researchers to forecast future climate shifts with unprecedented precision — from ice melt and sea-level rise to changes in heat and rainfall on a regional scale. It could also help unravel one of Europe’s greatest climate mysteries: the behavior of the AMOC, the massive Atlantic current that carries warm tropical waters northward, giving Europe its temperate climate.

🌊 Today in @Nature: Is the AMOC on the brink of collapse?

Unlikely before 2100—but the risks are real 🚨

We find Southern Ocean winds keep this vital ocean “heat engine” running, even under extreme #climatechange. But the Pacific holds a surprise…

Let’s explore 🧵👇 pic.twitter.com/Yp0aYg8qHa

— Jon Baker (@jonbaker_ocean) February 26, 2025

At this stage, the digital twin isn’t designed for daily weather forecasts but for long-term climate projections. Still, the fact that it models both fast and slow planetary processes offers a tantalizing glimpse into the future of meteorology — where long-term forecasts could one day be as reliable as short-term ones.

Karine Durand

Specialist for extreme weather and environment

A specialist in extreme weather phenomena and environmental issues, this journalist and TV host has been explaining climate topics since 2009. With over 15 years of experience in both French and American media, she is also an international speaker.

Trained in communication and environmental sciences, primarily in the United States, she shares her passion for vast natural landscapes and the impacts of climate change through her work on biodiversity and land management.