(Credits: Far Out / Alamy)

Mon 22 December 2025 21:05, UK

Frank Zappa once proclaimed that “without deviation from the norm, progress is not possible”.

The Beatles were widely regarded as harbingers of this same mantra. The Fab Four might’ve started with hand-holding mimicry of the likes of Buddy Holly, but soon after, they were lauded for their progressive ways, bringing a new baroque outlook to pop. They quickly shepherded the mainstream towards postmodernist collisions of art and technological stereo sound with records like Revolver and the revolutionary Sgt Pepper’s.

If anything, although they mightn’t have been to Zappa’s taste, they effectively trained the mainstream to expect that culture naturally veers towards the avant-garde the more popular it becomes. The Fab Four arose from nowhere as working-class lads, amassed unprecedented levels of popularity, and then got really rather weird. Other bands naturally followed suit, establishing a new norm of fame>to>experimentalism.

They helped psychedelia become widespread and accepted, heralding an all too brief revolution. This new style of music arose rapidly and quickly usurped more complex prevalences of jazz and classical. “[It] is much more primitive in its harmonic language,” Leonard Bernstein said of the rock ‘n’ roll revolution.

He added, “It relies more on the simple triad, the basic harmony of folk music. Never forget that this music employs a highly limited musical vocabulary; limited harmonically, rhythmically, and melodically. But within that restricted language, all these new adventures are simply extraordinary. Only think of the sheer originality of a Beatles tune.”

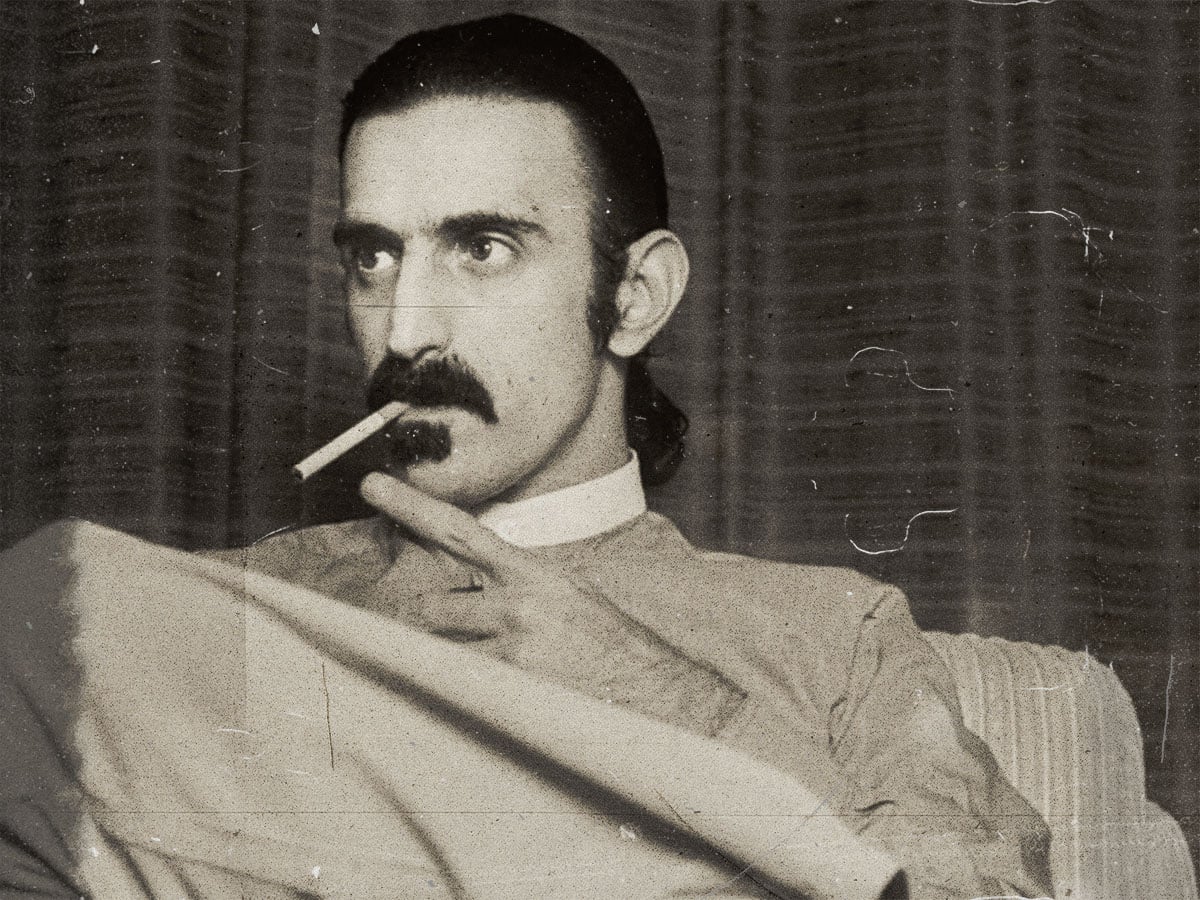

Frank Zappa performing in Copenhagen – 1967. (Credits: Bent Rej)

Frank Zappa performing in Copenhagen – 1967. (Credits: Bent Rej)

Zappa, ever the outsider, viewed the mainstream evolution of music as just another incremental adjustment to the usual standards, while he was racing wildly from the norm in his own unconventional way. His divergence wasn’t just in form but in challenging the entire meaning of what music had become. He saw The Beatles’ mid-1960s transformation as a false sense of liberation, so much so that he satirised both the band and their “movement” with his parody album cover for We’re Only In It For The Money.

And later down the line, he ditched subtle digs entirely and stated, “Everybody else thought they were God! I think that was not correct. They were just a good commercial group”. And seeing as though he once said, “Art is moving closer to commercialism and never the twain shall meet”, his disdain is no surprise.

However, it also has to be noted that Zappa came from an advertising background and during his brief time working that desk job, he concluded – long before many others – that modern music now had 50% to do with the image. Was this denigration of the Fab Four an engineered attempt to cultivate a fanbase of like-minded contrarians?

This thought gains credence when you consider what his PA, Pauline Butcher, would later say. “He worked out he wasn’t a pretty boy like The Beatles and the Rolling Stones,” she explained. “He didn’t play their kind of music, he didn’t even like it, and if he was going to get himself heard, he was going to have to do something radically different.”

Butcher continued, “He went out of his way to have outrageous photographs taken: the one on the toilet, the one with his pigtails sticking out like a spaniel, dressing up in women’s clothes. All these things were calculated because he had to get himself attention.”

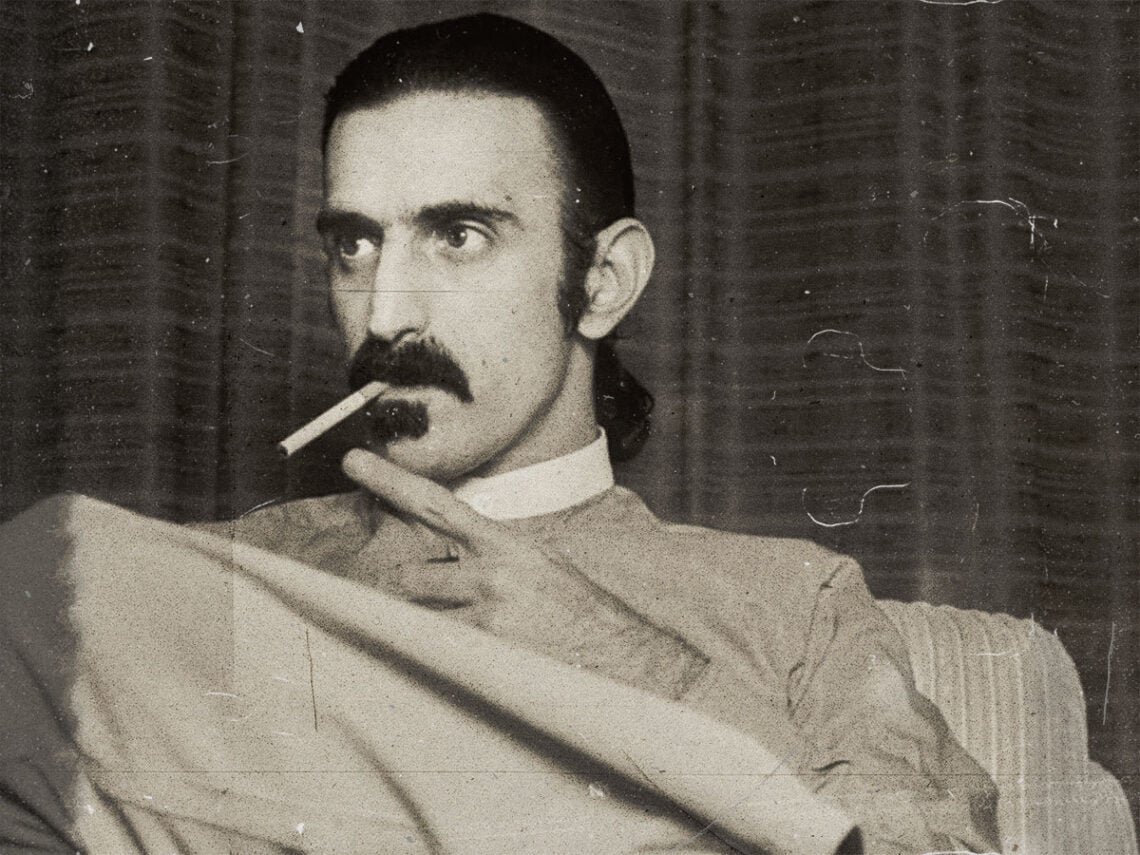

Mick Jagger and Keith Richards performing with The Rolling Stones. (Credits: Far Out / Alamy)

Mick Jagger and Keith Richards performing with The Rolling Stones. (Credits: Far Out / Alamy)

So, it is no surprise that he was fond of music that made no bones about putting itself happily on the precipice of acceptable culture. In fact, Zappa told the writer Clinton Heylin: “When I heard ‘Like a Rolling Stone’, I wanted to quit the music business”. He said of Bob Dylan’s scathing, society-probing opus: “I felt [that] if this wins and it does what it’s supposed to do, I don’t need to do anything else.”

And the same notion can be applied to why he loved The Rolling Stones’ bold effort Between the Buttons, whereby a hint of satire on the hippy subculture subverts the psychedelic twist to the album. In 1975, Zappa told the UK magazine Let It Rock that it was one of his favourite ever albums. “The American release – I don’t like the English version so much because it contains a totally different set of tunes,” he said.

Adding, “I understand that they don’t like the album very much, but I thought that it was an important piece of social comment at the time. I remember seeing Brian Jones very drunk in the Speakeasy one night and telling him I like it and thought it superior to Sergeant Pepper, whereupon he belched discreetly and turned around.”

So, while he might not have gotten much sense out of Jones on the matter, perhaps that’s partly why it appealed to him. The commentary on the record is tinged with acerbic absurdity, taking the sort of Duchampian approach that art that reflects an insane world should be suitably insane itself. Between the Buttons might not match Sgt Pepper for many, but for Zappa, it outstripped The Beatles in this pointed department.

Related Topics

The Far Out Beatles Newsletter

All the latest stories about The Beatles from the independent voice of culture.

Straight to your inbox.