Off Vancouver Island in British Columbia, scientists have recorded killer whales and dolphins hunting salmon together in coordinated teams.

The team followed nine northern resident killer whales and documented 258 encounters in which whales tailed foraging dolphins toward adult Chinook salmon.

Normally, these northern residents search for salmon on their own, while Pacific white-sided dolphins target much smaller fish and squid.

The new observations suggest both species gain something from teaming up, although scientists are still measuring how much each truly benefits.

Whales and dolphins collaborate

The researchers deployed biologgers, small tags that record an animal’s depth, movement, and sound, on nine whales and flew camera-equipped drones overhead.

Tag and drone footage showed whales repeatedly turning their bodies toward dolphins, with 25 clear course changes followed by shared foraging dives.

During dives, killer whales lined up behind dolphin paths while tracking their echolocation, high-frequency clicks used to sense prey at depth.

Different skills, shared hunt

Northern resident killer whales are apex predators that focus on adult Chinook salmon about 3 feet long and 30 pounds.

Pacific white-sided dolphins are generalist feeders, animals that eat several kinds of prey, often small fish and squid under two feet long.

Killer whales grip and tear salmon into pieces for relatives, whereas dolphins swallow smaller food whole and eat leftover bits from broken fish.

“Our footage shows that killer whales and dolphins may actually be cooperating to find and share prey-something never before documented in this population,” said study lead author Dr. Sarah Fortune, Canadian Wildlife Federation Chair at Dalhousie University.

Dolphins help whales find fish

Both species rely on echolocation clicks, and resident killer whale clicks peak between 12 and 19 kilohertz, according to one acoustic analysis.

In the new dataset, killer whales often shortened or silenced click trains when dolphins were nearby, while dolphins kept long bursts of buzzes.

Toothed whales send out sound in a tight, cone-shaped beam straight ahead, like a flashlight.

By turning their bodies as they swim, they can sweep that narrow beam across a wider area, helping them search for prey more effectively.

When dolphins joined hunts, tagged killer whales rolled their bodies less during deep chases, suggesting they depended more on dolphin scanning.

Cooperation, not theft

Biologists considered kleptoparasitism, a feeding strategy where one animal steals food from another that hunted, but the footage did not match.

Killer whales never lunged at, chased, or tail-slapped the dolphins, and researchers saw no abrupt retreats or evasive maneuvers from either species.

Dolphins made repeated dives to at least 200 feet while producing rapid buzzes and click trains linked with active hunting, indicating real effort.

That combination of tolerance, synchronized movements, and shared access to food fits better with cooperation.

Dolphins stay safer near whales

The dolphins also live alongside mammal-eating ecotypes, killer whale populations that specialize on seals, porpoises, and other marine mammals instead of fish.

Past field studies show these mammal-eaters often avoid the fish-eating residents, so dolphins clustering near residents may gain a moving safe zone.

This work did not capture many encounters with mammal-eating whales, so the anti-predator idea remains speculative rather than a demonstrated driver.

Researchers have suggested that dolphins might learn which whale calls signal danger versus safety, yet that cultural learning hypothesis still lacks direct tests.

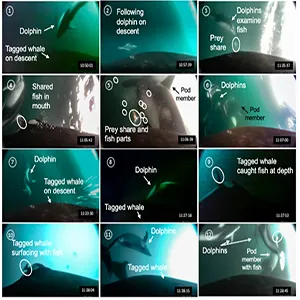

Cooperative foraging between dolphins and fish-eating killer whales. Video frame grabs, acoustic detections, and dive depths of killer whale I145 over a ~40 min period while Pacific white-sided dolphins were present. (B) Acoustic detections of dolphins (top) and killer whale I145 (bottom). Credit: Scientific Reports. Click image to enlarge.

Cooperative foraging between dolphins and fish-eating killer whales. Video frame grabs, acoustic detections, and dive depths of killer whale I145 over a ~40 min period while Pacific white-sided dolphins were present. (B) Acoustic detections of dolphins (top) and killer whale I145 (bottom). Credit: Scientific Reports. Click image to enlarge.

Pacific white-sided dolphins move quickly in large groups and expend a lot of energy, making dense clusters of calorie-rich fish especially valuable.

By shadowing salmon specialists, dolphins can sometimes add pieces of large Chinook to diets otherwise built around smaller schooling fish.

In one event, dolphins scavenged bits from a Chinook that a killer whale carried to the surface, tore apart, and shared with relatives.

Salmon scraps may be modest in quantity, yet occasional high-energy bites could help dolphins when smaller fish are patchy or scarce.

Following the underwater action

The biologging tags used in this project were suction-cup devices that recorded three-dimensional motion, underwater video, and sound from each tagged whale.

Drone footage added a top-down view of groups, letting scientists track how dolphins and killer whales aligned positions and dives over minutes.

By matching video frames, acceleration spikes, and crunching sounds from salmon kills, researchers tied dolphin positions to when whales captured and shared prey.

The same toolkit is helping scientists examine interspecific interactions – repeated encounters between species that might reveal cooperation or competition under changing ocean conditions.

Why this partnership matters

For fish-eating killer whales, partnering with dolphins could reduce searching effort for Chinook while still providing the large, fatty salmon their bodies require.

Efficiency may matter because many Chinook runs along the Pacific coast are depressed, and the whales depend heavily on them year-round.

The partnership also hints at social learning, since cooperative tactics such as these are often passed within whale families rather than hard-wired genetically.

Future work will track whales and dolphins across seasons to learn how often they hunt together and whether other populations use this strategy.

The study is published in Scientific Reports.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–