A pair of fossils once thought to be the youngest woolly mammoth remains ever found in Alaska have turned out to be something entirely different: whale bones. What seemed like a groundbreaking discovery about the extinction of mammoths has instead become a puzzling case of mistaken identity in the world of paleontology. Radiocarbon dating revealed the bones were much younger than expected, and not from a mammoth at all.

The bones, discovered in the 1950s, had sat in the University of Alaska Museum of the North’s collection for decades, with no one questioning their origin. However, when scientists recently radiocarbon-dated the specimens, they found themselves thrown off track. The results showed that the fossils were between 1,900 and 2,700 years old, far too recent for mammoths, which disappeared from mainland Alaska around 10,000 years ago. The hunt to uncover the truth led researchers to a surprising conclusion.

The Fossil Discovery That Started It All

In the early 1950s, Otto Geist, a naturalist exploring the Alaskan wilderness, found a pair of fossilized backbones in the area north of Fairbanks, near Dome Creek. The bones were large and well-preserved, and at the time, Geist identified them as woolly mammoth remains. For decades, the fossils were stored at the University of Alaska Museum of the North, where they were cataloged as part of the mammoth collection.

Everything changed in 2022 when researchers launched a program called “Adopt-a-Mammoth”, aimed at radiocarbon dating the mammoth bones in the museum’s collection. When the results came back, they puzzled the entire team. According to research published in the Journal of Quaternary Science, the fossils are roughly 10,000 years younger than true mammoth remains from mainland Alaska.

A star highlights the site of Dome City in central Alaska. Credit: UAF Geophysical Institute

A star highlights the site of Dome City in central Alaska. Credit: UAF Geophysical Institute

Genetic Clues Reveal What Really Happened

The surprising results from the radiocarbon dating led researchers to take a closer look at the fossils using DNA testing. What they found was a complete shock: the bones didn’t belong to mammoths at all, but to two species of whales, a North Pacific right whale and a minke whale. According to Matthew Wooller, an ecologist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the discovery made no sense:

“Here we had two whale specimens, not just that, but two separate species of whale,” he added. “It just kept getting weirder and weirder.”

He suggested that the bones might have been misattributed when they were originally cataloged in the 1950s. Geist, who collected fossils from all over Alaska, might have mistakenly labeled the bones from a coastal area as being from the Fairbanks region.

“That’s the least interesting [explanation], just a kind of a screw up in record keeping, which, it happens,”

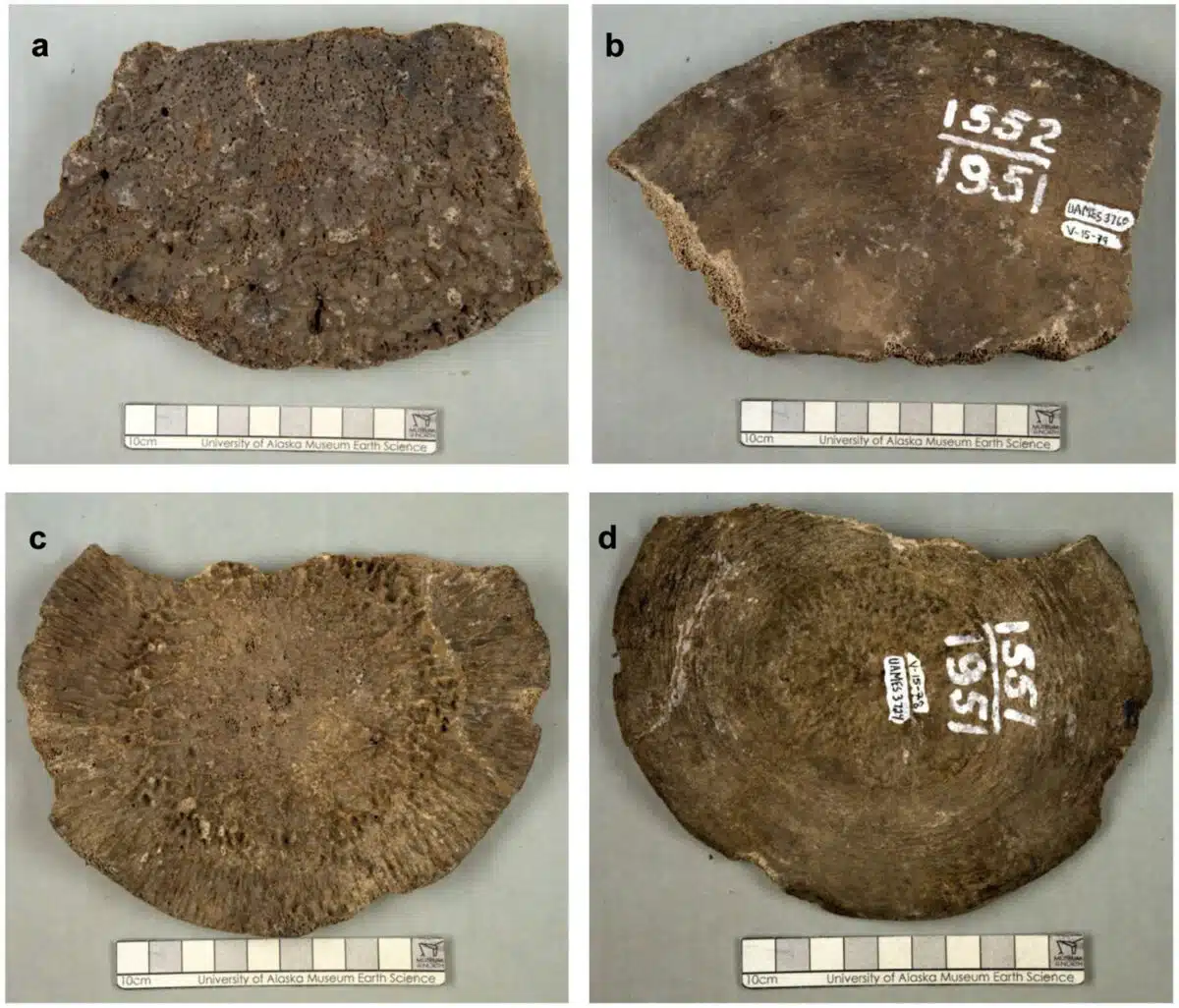

These fossils of whale vertebrae were gathered by Otto Geist. Credit: UA Museum of the North

These fossils of whale vertebrae were gathered by Otto Geist. Credit: UA Museum of the North

How Did Whale Bones End Up 250 Miles Inland?

Even after the identification was corrected, the researchers were left with another mystery: How did whale bones end up so far inland? Dome Creek, the site of the discovery, is about 250 miles from the coast, an unlikely distance for a whale to travel.

Some species of whales, like the minke whale, are known to swim upriver in pursuit of food, but Dome Creek is too small to accommodate this theory. The researchers also considered the possibility that scavenger animals could have brought the bones inland, though this seemed unlikely.

To make things even more intriguing, scientists later suggested that the whale bones might have been transported inland and used by early Indigenous peoples.

“It might have been used as a plate, a platter or for carving,” said Patrick Druckenmiller, director of the University of Alaska Museum of the North, “but the bone hasn’t been modified.”