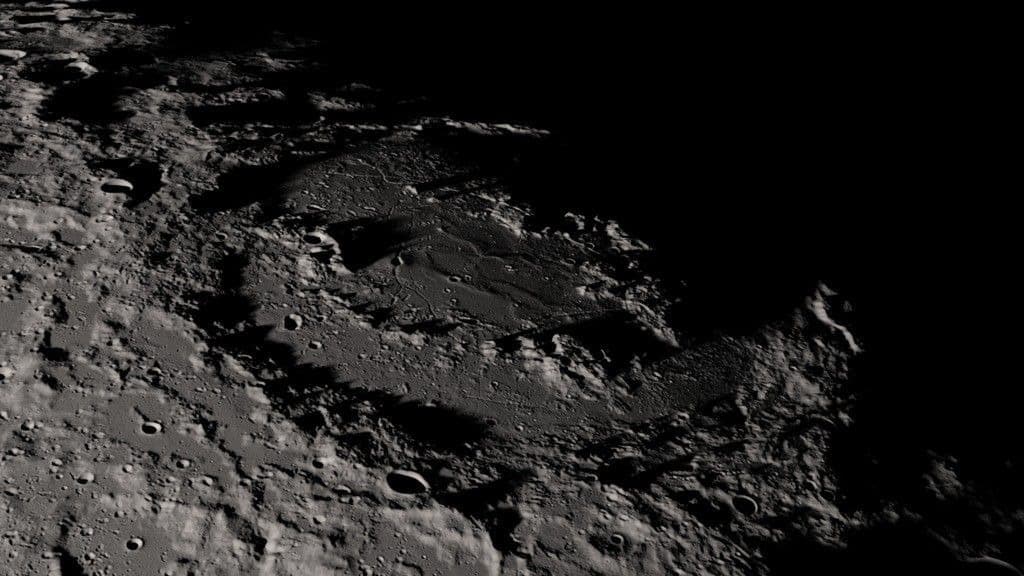

A brief, intense flash illuminated the Moon’s dark surface this month, recorded by telescopes at the Armagh Observatory and Planetarium in Northern Ireland. The event, lasting less than a second, marked a confirmed meteoroid collision with the lunar surface. It has drawn wide attention from researchers studying how often such impacts occur and what they reveal about space debris striking the Moon.

The observation is significant because the flash was captured in real time by calibrated lunar monitoring instruments. The Armagh team’s confirmation adds to an expanding record of verified lunar impact flashes, which help scientists study high-speed collisions on a body with no atmosphere.

Unlike Earth, the Moon cannot burn up small objects as they enter. Even meteoroids a few centimetres across reach its surface intact, travelling more than 60,000 kilometres per hour and releasing energy equivalent to hundreds of kilograms of TNT. Detecting these brief bursts of light enables researchers to estimate how often impacts occur and the size of the debris responsible.

The event took place at 19:32 UTC on 19 December 2025, as reported by the Armagh Observatory. Initial analysis indicates the impact was caused by a natural meteoroid rather than orbital debris. The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter is expected to search for the new crater once the region receives sunlight.

Confirming a Verified Lunar Flash

Astronomers first noticed the flash while reviewing footage from Armagh’s Lunar Monitoring Project, which continuously tracks the Moon’s nightside using sensitive optical systems. A second observatory later confirmed the detection, reducing the chance of false signals from cosmic rays or instrument noise.

In a statement published by the Armagh Planetarium, researchers described the event as an unmistakable lunar impact flash, visible for a fraction of a second. It was among the brightest flashes recorded in recent years. The team is now examining its brightness curve, which reveals how the light changed over time and helps estimate the impactor’s energy and mass.

Armagh’s network of telescopes has monitored the Moon since 2015, collecting data on flashes too faint to be seen with the naked eye. Its automated systems record continuous video at high frame rates, flagging potential impact events for later human verification.

Comparable monitoring efforts are conducted by NASA’s Meteoroid Environment Office in Huntsville, Alabama, which operates one of the world’s longest-running lunar impact detection programs. Data from these independent networks contribute to global models of meteoroid flux, improving understanding of the debris environment near Earth and the Moon.

What Likely Hit the Moon

The source of the December impact is still being analysed. Researchers are comparing the time and location of the flash with known meteor showers, including the Geminid and Ursid streams that peak in mid-December. Matching the event to a meteor stream could identify the parent comet or asteroid responsible.

Based on brightness and duration, scientists estimate the meteoroid weighed only a few kilograms. When such an object strikes the lunar regolith, the thin layer of dust and rock covering the Moon, it vaporises instantly and generates a luminous plume visible from Earth.

When sunlight reaches the region in the coming weeks, high-resolution cameras aboard NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter may locate the fresh crater. Similar follow-ups have confirmed earlier impacts, allowing comparisons between optical flashes and crater sizes to refine energy estimates.

Importance for Lunar Exploration and Safety

Tracking lunar impacts has become increasingly relevant for space exploration. Agencies planning crewed and robotic missions, including NASA’s Artemis program, require accurate assessments of micrometeoroid activity to design safer lunar habitats and equipment.

Research from the NASA Meteoroid Environment Office indicates that the Moon experiences several small impacts every hour, though only the largest generate flashes visible from Earth. Understanding the size and energy of these events helps engineers predict long-term erosion and risks to surface structures.

The lunar surface serves as a natural indicator of how often meteoroids also pass through Earth’s orbital space. Monitoring impacts there provides a clearer view of potential hazards to satellites, spacecraft, and future lunar infrastructure.