In 2006, scientists made an extraordinary discovery off the coast of Iceland: a clam that was over 500 years old. This remarkable creature, later named Ming, became the oldest individual animal ever recorded. However, the irony lies in the fact that Ming’s discovery also led to its untimely death. The event sparked curiosity about longevity in the animal kingdom, particularly among bivalves like the ocean quahog clam.

Ming the Clam: A 507-Year-Old Marvel

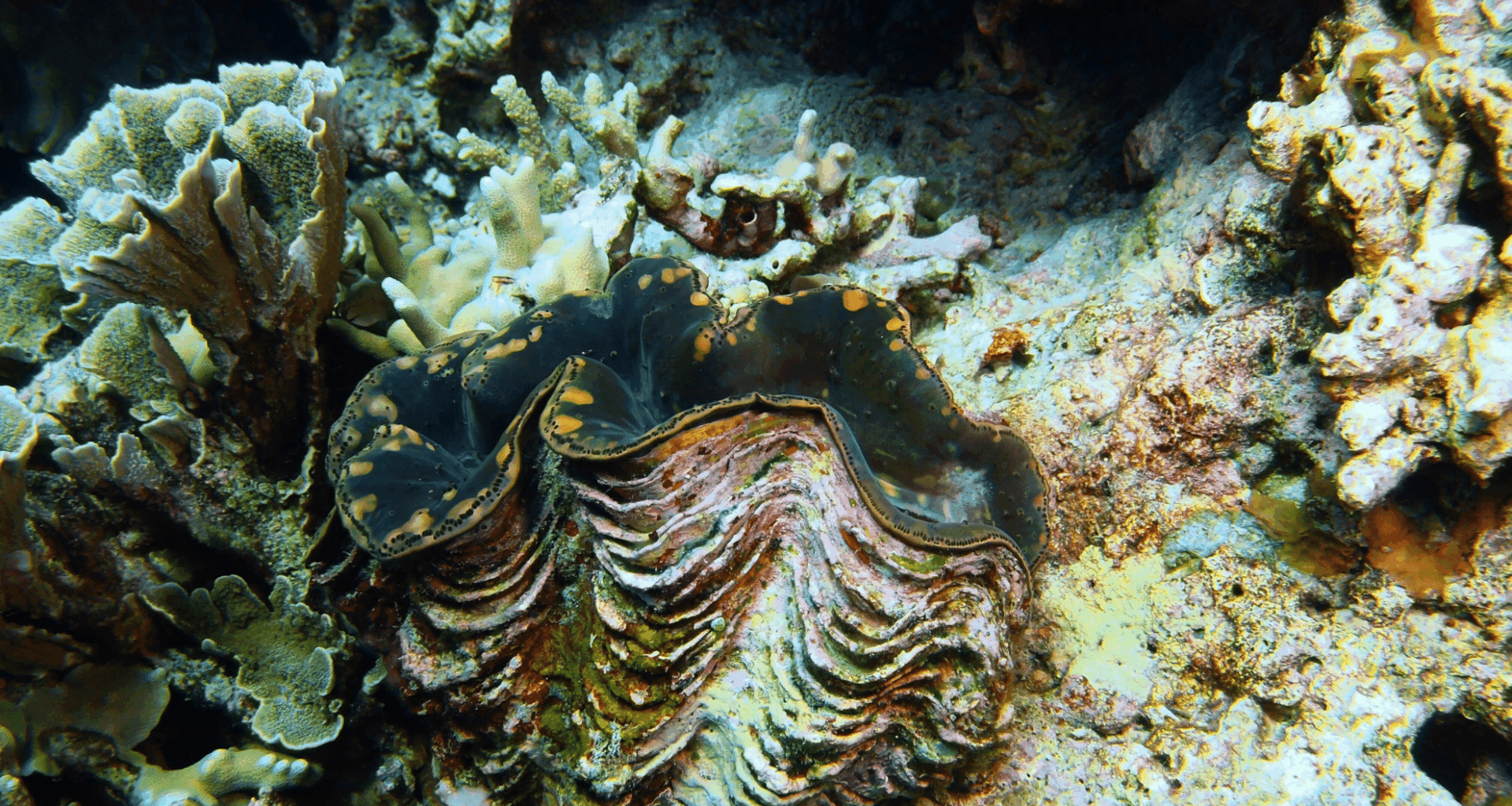

Ming’s discovery brought attention to the surprising longevity of certain marine species. The ocean quahog clam, scientifically known as Arctica islandica, has long been known for its impressive lifespan, often living for over a century. However, Ming, who was found in 2006, surpassed expectations. After being dredged from the ocean floor, scientists conducted extensive studies to determine its age. They used a method similar to tree ring analysis, counting the growth lines in its shell to assess its age, eventually confirming that Ming was 507 years old. This remarkable finding placed Ming’s birth around 1499 CE, during the Ming Dynasty in China.

As the clam’s discovery gained attention, the scientific community marveled at how it had survived for more than five centuries. Its lifespan is extraordinary, especially when compared to other species. In fact, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) explains that “some massive species found in shallow waters are estimated to live more than 2,300 years.” While Ming was not quite that old, its age remains remarkable by any standard, and it became a symbol of nature’s ability to defy expectations.

The Science Behind Ming’s Longevity

Understanding how Ming lived for over half a millennium involves studying the unique biology of the ocean quahog. Arctica islandica clams possess a fascinating ability to grow slowly and steadily over time, thanks to their remarkably low metabolism. This slow pace of life contributes to their longevity, allowing them to endure for centuries. Unlike many animals, the clam’s cellular structure shows little sign of aging.

“Bivalve mollusc valves contain a record of their ontogeny in the form of internal annual growth lines, and higher resolution daily and tidal bands, which can be observed microscopically in acetate peel replicas or thin sections,” a paper on the clam, published in SAGE Journals, explains.

These growth increments are crucial to understanding the clam’s age, providing a detailed record of its life. By counting the growth lines in the shell, scientists can accurately determine the clam’s age. The shell acts as a natural archive of the animal’s history.

An Unfortunate Discovery: How Ming Was Killed

In a cruel twist of fate, the very discovery of Ming’s age led to its death. When the clam was first brought to the surface, scientists were eager to determine its age and learn more about its long life. However, during the process of extracting and studying Ming, the clam was inadvertently frozen. The freezing likely caused irreversible damage to its delicate internal structures. Tragically, Ming did not survive the ordeal. This incident highlights the vulnerability of ancient creatures when subjected to human intervention, no matter how well-intentioned.

The clam’s death also sparked a broader discussion about the ethics of studying such long-lived animals. While scientists had the opportunity to learn invaluable information about Arctica islandica and its remarkable life cycle, Ming’s untimely end underscored the risks involved in studying creatures that have existed for centuries in a delicate balance with their environment.

The Evolutionary Significance of Ming

Ming’s extraordinary age places it among the oldest known individual animals, and its story offers insights into the evolutionary strategies that enable such longevity. Studies have shown that animals like Ming have evolved mechanisms to slow their metabolic rates, a trait that appears to be linked to longer lifespans. These clams grow at a pace that ensures they remain in a state of equilibrium for much of their lives, avoiding the rapid aging that affects many other species.

“Annual band counting from the sectioned shell revealed that this clam lived for more than 405 [years],” a paper on the clam explains, “making it the longest-lived mollusk and possibly the oldest non-colonial animal yet documented.” This finding not only enhances our understanding of aging in the animal kingdom but also provides a glimpse into how long-lived organisms manage cellular maintenance over centuries.