Standing in spacious grounds among pine trees, the Brasserie restaurant at the Copthorne Hotel was once a much-loved venue where local families enjoyed a meal out at weekends.

The hotel website still chirps that the Brasserie, overlooking a Japanese-style lake and courtyard, offers ‘British cuisine’, including a traditional Sunday roast.

‘Your little ones will love the play area and children’s menu too,’ it burbles.

Yet today, the Brasserie is no longer open to the public. The Copthorne, just three miles from Gatwick in West Sussex, became a migrant hotel in 2021 offering accommodation to hundreds of Afghan asylum seekers.

When they moved on, it became home to 1,000 men, women, and children of different nationalities, many of whom have arrived illegally on Channel traffickers’ boats.

This week, as Christmas beckoned, I visited the Copthorne, so becoming the first newspaper journalist to see inside a government-run migrant hotel.

The hotel is just one of the hundreds scattered around the country which, despite promises by Labour to shut them down and ‘smash’ the smuggling gangs, remain a central cog of an asylum system beleaguered by the sheer numbers of arrivals.

I had been invited to tour the Copthorne by a group of migrants hailing from a range of countries including Iraq, Iran, Palestine and Eritrea, whom I met earlier this year in Calais shanty camps as they waited to make illegal crossings to Britain.

The Brasserie restaurant at the Copthorne Hotel was once a much-loved family venue. Yet today, it is no longer open to the public after the hotel, just three miles from Gatwick in West Sussex, became migrant accommodation in 2021. Pictured: Sue Reid with a group of migrants living in the hotel, who invited her to tour it

This week, as Christmas beckoned, Sue Reid (pictured at the hotel) visited the Copthorne, so becoming the first newspaper journalist to see inside a government-run migrant hotel

What she found was the good, the bad and, indeed, the ugly. Pictured: Sue Reid inside the hotel

What I found was the good, the bad and, indeed, the ugly.

I met a boastful migrant drug dealer, black marketeers working for cash at local car washes and construction sites, and some who have languished here at the Copthorne for three years at taxpayers’ expense because, as they put it, ‘no one has decided what to do with us’.

Incredibly, I was told that migrants can check out for a ‘three or four-day’ break from the hotel to visit their friends and relatives around Britain. ‘They tell the reception desk the date they are going and when they will return,’ said a young Syrian Kurdish man as we shared a cigarette and a coffee in the courtyard outside the Brasserie, which is now the migrants’ main restaurant.

‘The room is still paid for when they are on their little holiday,’ he added. ‘Of course, some never come back. They join their own communities and slip into underworld work in the UK.’

Another migrant from North Africa said: ‘We are free to come and go as we please. We are not in a prison, although it costs £3 each way to go on the bus to Crawley and the shops. If we walk, it is an hour and 20 minutes.’

They are paid just under £10 each a week in pocket money loaded on to a special Home Office cash card – although, for some, there are also alternative sources of income.

‘It is hard for us because e-bikes are no longer allowed on the premises,’ he said. ‘They were used by some here to go out and work each day on the black market. Now, the bosses of the car wash and construction places come and pick them up in the morning instead, and deliver them back at night. There aren’t any real checks on us.’

When I visited, it was early evening. I arrived with my passport and my birth certificate, ready to prove my identity. However, the documents were requested neither at the main gate nor by security guards at the entrance to the hotel itself.

I signed in and was given a red lanyard saying ‘Visitor’, before my migrant hosts offered me coffee (from the Brasserie, where supper cooked by Indian chefs was under way).

Then they showed me around and told me their personal stories. On Monday night this week, the place was calm, orderly and warm – there are no worries about energy bills for the residents.

I saw two small Christmas trees (one outside the Brasserie and another in the lobby) but no other sign that a Christian festival was taking place.

‘Apart from a few [Christian] Eritreans, the rest of us are from Islamic countries,’ explained one Iraqi migrant who has been at the hotel for seven months.

‘We won’t be celebrating your Christmas here with a special lunch. Anyway, the Brasserie chefs are Indian.

‘They give us rice, which we like, but it is always too spicy because that is how they cook it back home.’

The walls of the hotel are still bedecked with incongruous paintings of idyllic British scenes in mass-produced golden frames. A billiard table stands unused ‘because the balls and sticks [cues] disappeared a long time ago’ my hosts tell me.

The carpets are frayed from the enormous footfall of sandals and trainers over the past four years.

She met some who have languished at the Copthorne (pictured, as migrant accommodation) for three years at taxpayers’ expense because, as they put it, ‘no one has decided what to do with us’

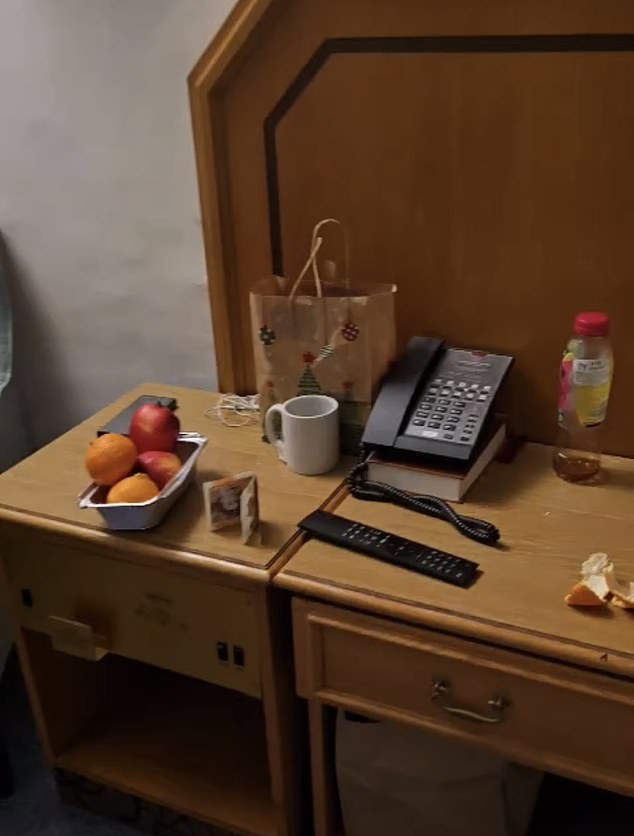

Migrants are paid just under £10 each a week in pocket money loaded on to a special Home Office cash card – although, for some, there are also alternative sources of income. Pictured: Bank notes on a bedside table in a room at the Copthorne

I am shown a bedroom now shared by two Middle Eastern migrants, where the luxurious bed of yesteryear has been replaced with two Home Office singles with cheap, spongy mattresses. The bathroom paint is peeling and the tiles on the wall are dirty.

‘There is a laundry service once a week when the sheets are changed by housekeeping staff who are from Thailand and have visas to work in Britain. There is no one English working at the hotel apart from a few security guards,’ the occupants of the room explain.

Yet the Copthorne seems to tick along. There are entire families here and, occasionally, I see a child poking his or her head out of a doorway or running down the long corridor.

An African mother carries a newborn baby past me. In a sitting room, a couple of teenage boys are glued to their laptops as they play a game together shouting in a foreign language.

But, be in no doubt, there is an undercurrent of discontent among the migrants themselves – mainly about their ‘human rights’ to a home of their own, which traffickers and charities in Calais assured them they will get – and among locals, who have mounted flag-waving protests outside this hotel and outside another Copthorne a few miles away, where a further 500 migrants are in residence.

One local man recently wrote on social media: ‘My last trip to the West Sussex Copthorne [it is not made clear which one of the two he means] was for a meal with my father in 2014. He reminded me of the business meetings he had there in the 1980s, and how he had such fond memories of staying and hosting clients. Not one inch of Britain is not affected negatively by our traitorous Government.’

In the lobby, there are piles of Home Office leaflets in a multitude of languages, including English, Arabic and European tongues, which inform the migrants what to expect from what is described as ‘initial accommodation’.

It warns that waiting times to ‘move on’ can be long because of a shortage of local housing and a significant increase in those arriving in the UK ‘seeking protection’.

Many clearly see Britain as their ‘last chance’ after asylum-shopping through Europe – and being turned down elsewhere.

‘So many arriving have a smattering of German because they have been rejected from there,’ a migrant tells me.

‘I, myself, was refused the right stay in Germany as an asylum seeker. I ran, fearing deportation if I waited. I was in such a hurry I left all my clothes there. I had nothing when I went by train to Paris, then Calais and got on a boat to Britain.’

I also found migrants at the Copthorne who have blatantly lied their way into this country. Egyptians, Moroccans, Algerians, and Tunisians (whose home countries are deemed by the Home Office to be safe for deportation flights) were pointed out to me by my hosts. ‘Many pretend to be Libyans because they will not be returned there by your Home Office as it is a dangerous country,’ said one of my courtyard friends.

‘They learn-up about Libya, such as remembering street names in the capital, before they leave France so they can fool the Home Office when they are questioned at the Kent border. The Iraqis pretend to be Libyans, too.’

There are plenty of Eritreans in the hotel. They are fleeing an evil, totalitarian regime where all men are forced, often indefinitely, into the army aged 19 to fight neighbouring Ethiopia in a bitter ongoing border dispute.

A group of three in their 20s told me that they want to send money home to help their loved ones but that, if they do, the country’s dictator would burden their families with a ‘special’ punitive tax for having a relative who has fled abroad.

I met a Middle Eastern father in his 30s who, in March, boarded a Channel boat along with his father, mother, wife and several young children. They have lived in the hotel ever since.

Sue Reid was shown a bedroom (pictured) now shared by two Middle Eastern migrants, where the luxurious bed of yesteryear has been replaced with two Home Office singles with cheap, spongy mattresses

Be in no doubt, there is an undercurrent of discontent among the migrants themselves – mainly about their ‘human rights’ to a home of their own. Pictured: A bedroom at the Copthorne

‘I was in Britain a few years back’, he said, ‘and I liked it then. I went back all the way to my home country to collect my family to bring them here.’

This extraordinary character told me he worked on the black market in East Sussex and London for extra money.

‘Oh, what do you do?’ I asked him, innocently enough.

‘I am a drug dealer,’ he replied without shame. ‘That’s what happens if you don’t let us work. I have grown to hate Britain and now I am trapped here in this hotel.’

I talked to 20 or so migrants during my three-hour visit. A frequent complaint was that they are bored stiff, despite the English lessons, singing and music classes (provided by a renowned arts foundation) on offer, and despite frequent visits from refugee-charity volunteers. ‘They promise to help but do nothing for us. They just talk at us,’ said two Iranian men in faltering English.

The hotel is plastered with posters put up by Migrant Help, a charity which received £47million from the government last year to run an advice helpline for migrants (including details of how to complain to the Home Office).

I spoke to many who tried calling and was repeatedly told that ‘they do not answer’, or that ‘you get left in the queuing system for hours’.

One migrant claimed: ‘I have never heard of one person who has been helped by this charity.’

Perhaps the last word should go to a 29-year-old Libyan.

He came on a boat in September, has been refused asylum but is now appealing against the decision.

An educated man, he said through my translator: ‘What the British government has done for us is good. We just need to live normal lives, including studying and working. Then this nightmare will end. The smugglers and the charities in Calais did not tell us there were so many thousands in the queue ahead of us. We only realise it now.’

He finished his plea with the word ‘Inshallah’, used by Muslims and Arabic speakers of all faiths with the meaning ‘God willing’. He is relying on divine intervention to rescue him.

I responded with a few home truths: that more than 41,000 people, mostly young, single, men like him have sailed illegally across the Channel this year, 1,374 last week alone, on rubber boats.

Many of them, I added, will join the 36,000 migrants living free in Home Office hotels, with three meals a day, no bills whatsoever, as more and more Britons grow angry at paying higher taxes for the £5.77million-a-day cost of an asylum free-for-all which is wildly out of kilter with British sentiment.

I said that even the Home Office appears to suspect it is being taken for a ride.

In an unusual statement on the social media site X this week, the department warned: ‘As asylum claims fall across Europe, in the UK they are rising. Whilst some are genuine refugees, others seek to game the system. Even genuine refugees are crossing safe countries (in the EU) to come here.’

Then, it was time to go. Three of my hosts led me from the Brasserie courtyard to the hotel entrance. One planted a kiss on my forehead and gave me a tangerine as a gift. I called ‘Happy Christmas’ as I drove away – but never heard a response.