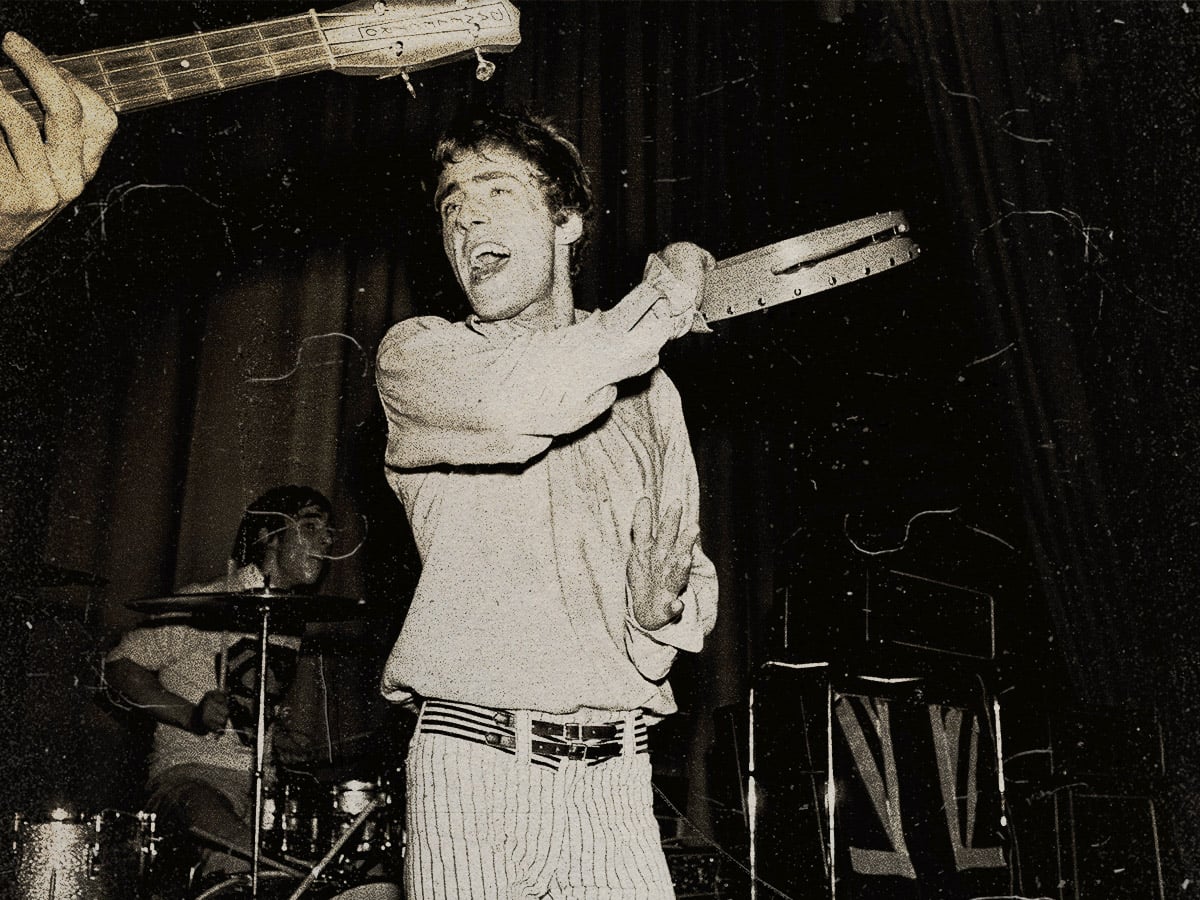

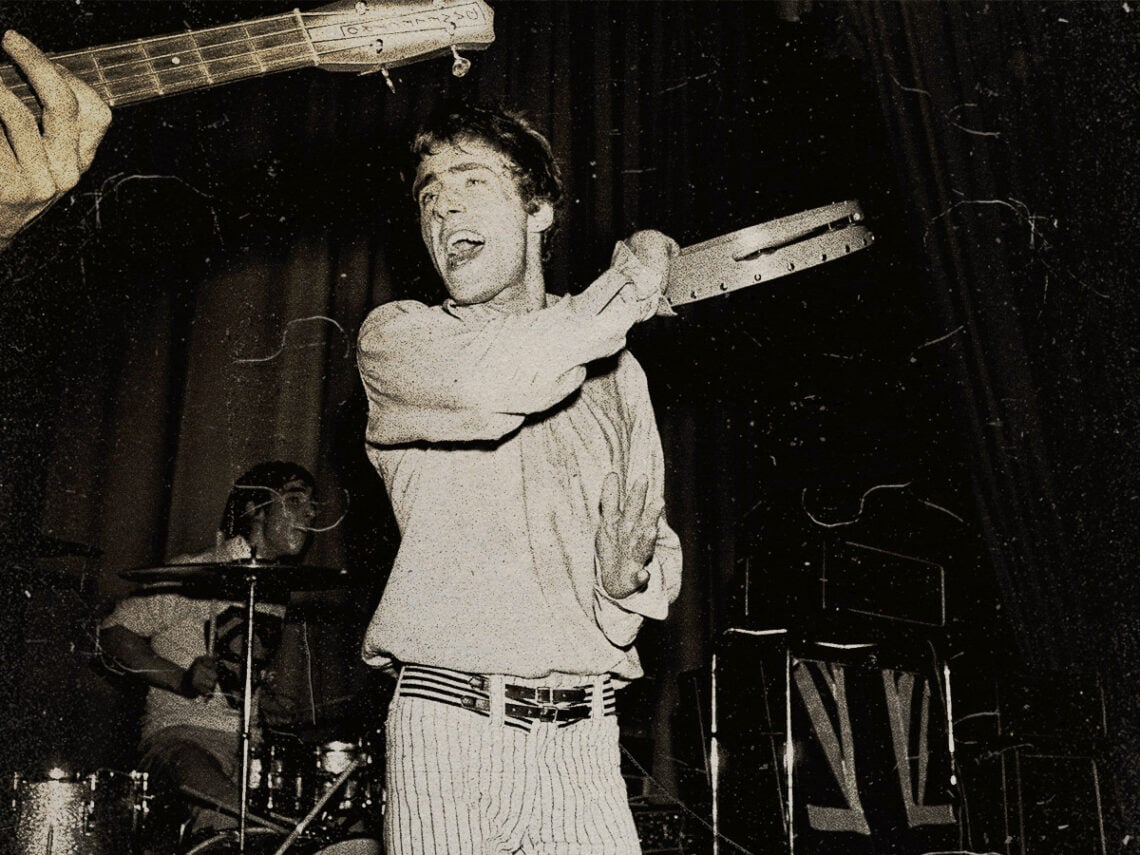

(Credits: Bent Rej)

Mon 29 December 2025 10:00, UK

Not every classic rock band is meant to be perfect. Even though it’s easy to hold up the best songwriters of all time as having little to no mistakes, there will always be those few songs where they feel like they could have done better. As for Roger Daltrey, one of The Who’s finest hours has a glaring problem regarding production.

While The Who may be seen today as the brainchild of Pete Townshend, Daltrey was the one who founded the group in the early 1960s, playing a rock and roll take on classic R&B and soul tunes coming over from the US. Once Townshend started to write his material and blow the doors off the hinges with ‘My Generation’, the band began to come into their own as a creative unit on albums like A Quick One.

Outside of the massive riffs that went into every song, Townshend was slowly picking away at the idea of making a grandiose statement with his songs. Framing the following albums as rock operas, Tommy would become one of the most daring statements of Townshend’s career, taking the basis of a deaf, dumb, and blind boy and marrying it to the most extravagant hard rock the world had ever seen.

Although Townshend’s plans for a follow-up to the album in Lifehouse fell through, the collection of scraps left over for Who’s Next became one of the biggest successes of their career, boasting massive moments like ‘Won’t Get Fooled Again’ and ‘Baba O’Riley’. While Daltrey would consider Who’s Next among the best work the band ever made, Townshend wasn’t done dreaming bigger.

Coming up with yet another story for Quadrophenia, Townshend wanted to make different themes that played into the operatic side of the record, with various musical pieces coming in and out of the mix. The production would also follow suit, panning the instruments in such a way as to create quadrophonic sound and creating the sensation of the music surrounding the listener whenever they put it on the turntable.

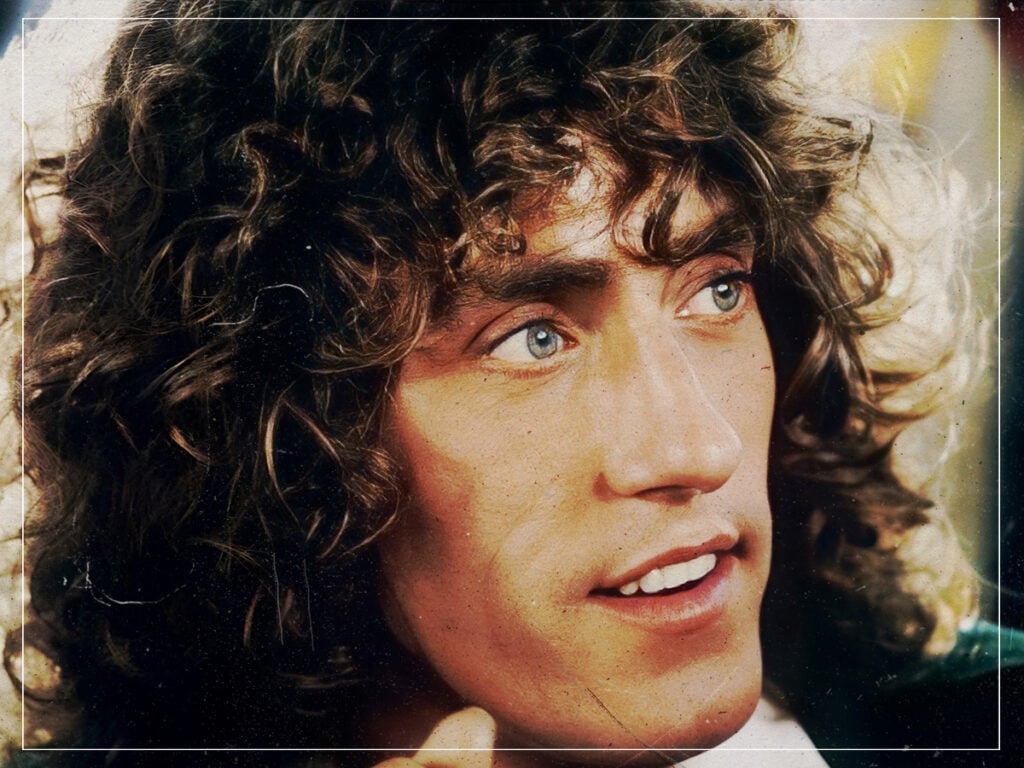

Behind the blue eyes of Roger Daltrey. (Credits: Far Out / Alamy)

Behind the blue eyes of Roger Daltrey. (Credits: Far Out / Alamy)

For Daltrey, the voice was always meant to sit front and centre. Unlike many singers of the era who were happy to be folded into the band’s overall sound, Daltrey treated his vocals as a physical force, something that needed space to hit with full impact. Every scream, roar, and sustained note was shaped by breath control and sheer effort, making clarity essential to the performance landing as intended.

That philosophy often put him at odds with more experimental production choices. While Townshend was fascinated by texture and atmosphere, Daltrey was concerned with immediacy and presence. To him, a song lived or died on whether the emotion could be felt instantly, without being filtered or softened by studio effects that dulled its edge.

While Townshend thought the technique would take rock into unknown territory, Daltrey was not as impressed with the new technology. Considering how much power Daltrey put into his performances, he would later recall that the new approach to recording led to some of his finest work being buried in the mix.

When talking about the album years after, Daltrey pointed fingers at mixer Ron Nevison for putting too much echo on his vocals, saying, “It just makes the vocal sound thin. It was the biggest recording mistake we ever made. The echo diminishes the character, as far as I’m concerned. It always pissed me off. From day one, I just fucking hated the sound of it. He did that to my voice, and I’ve never forgiven Ron for it”.

Given the massive strides that Daltrey took to get his voice into shape for the record, though, it’s pretty clear why he would be upset to hear everything kept at a distance on the final record. Then again, if the final version of ‘Love Reign O’er Me’ is the inferior version in Daltrey’s mind, one can only imagine what the dry version of the song may have sounded like.

Related Topics