Deep inside some magnetic materials, electrons can behave in ways that seem to defy common sense. Instead of lining up neatly like tiny compass needles, as magnets usually do, their spins remain restless, fluctuating endlessly even near absolute zero.

Physicists call this strange state a quantum spin liquid, and for decades it has been one of the most elusive phases of matter in physics. Now, a new study reveals some of the clearest evidence yet that this exotic state truly exists in real materials.

By studying a carefully crafted crystal with a special atomic pattern, they show that quantum spin liquids may not be rare cases but a universal feature of a whole class of materials. This result could change how scientists think about quantum matter.

What makes quantum spin liquids hard to prove

The biggest challenge in proving the existence of quantum spin liquids is that they leave no obvious fingerprints. In ordinary magnets, spins form ordered patterns that are easy to detect.

In quantum spin liquids, however, the spins never settle down, and their behavior is governed by deep quantum entanglement—a phenomenon where particles remain linked even when separated.

“I’ve been interested in understanding quantum spin liquids for the past 20+ years. These are fascinating new states of quantum matter. In principle, their ground states may possess long-range quantum entanglement, which is extremely rare in real materials,” Young Lee, senior study author and a professor at Stanford, said.

Until now, scientists could not be sure whether unusual signals seen in experiments were truly signs of a quantum spin liquid or just quirks of specific materials. To tackle this problem, the study authors focused on materials with a kagome lattice, a geometric arrangement of atoms resembling a pattern of interlocking triangles.

This structure naturally frustrates magnetic order, making it a prime candidate for hosting quantum spin liquids. In previous studies, the researchers studied a kagome material called herbertsmithite, where they detected unusual magnetic excitations.

However, critics wondered—were those excitations universal, or unique to that one compound?

Testing a new kagome material for universal behavior

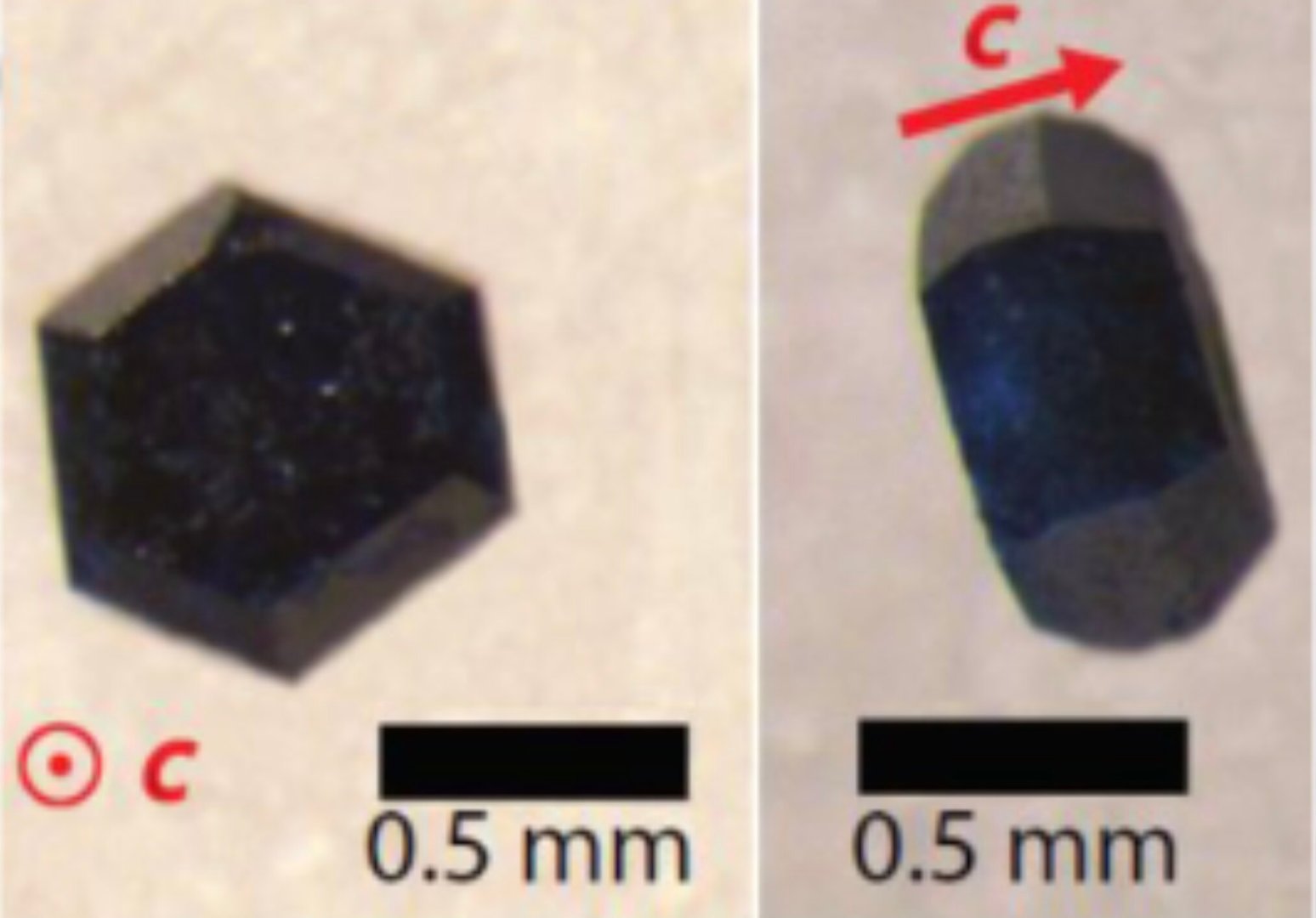

Quantum spin liquid candidate Zn-barlowite. Source: Lee group, Stanford University

Quantum spin liquid candidate Zn-barlowite. Source: Lee group, Stanford University

To answer the above-mentioned question, the researchers synthesized high-quality single crystals of a different kagome material called Zn-barlowite. Creating such crystals is difficult but crucial, because clean, well-ordered samples allow precise measurements.

The researchers cooled the crystals to extremely low temperatures to observe their lowest-energy, or ground, state. They then fired neutrons into the material using high-resolution inelastic neutron scattering.

Neutrons are ideal probes because they can penetrate deep into the crystal and interact directly with the spins of electrons. By analyzing how the neutrons scattered, the scientists could see how spins were correlated across space and how they fluctuated over time.

What they found was striking. Instead of behaving like conventional magnetic waves called magnons, the excitations broke apart into smaller pieces known as spinons. Our “measurements revealed that the fundamental excitations of the kagome spins appear in the form of ‘spinons’ which are fractionalized pieces of typical ‘magnon’ excitations,” Lee said.

According to the researchers, this is something that can only happen in strongly quantum-entangled systems. What’s even more compelling is that the spinon behavior in Zn-barlowite closely mirrored what the team had previously seen in herbertsmithite.

This finding suggests that both materials host the same underlying quantum spin liquid state, pointing to a universal phenomenon rather than an isolated case.

Now we must catch the entanglement

This work marks an important step toward a long-standing goal in condensed matter physics, i.e., reaching broad agreement on at least one real material that unquestionably hosts a quantum spin liquid ground state.

By showing that two different kagome materials exhibit the same exotic excitations and that these observations align with theory, the study strengthens the case that quantum spin liquids are real, robust phases of matter.

In the long term, these states could have far-reaching implications. For instance, quantum spin liquids naturally possess long-range quantum entanglement, a key ingredient for quantum computing, secure information storage, and other quantum technologies.

However, practical applications are still far away. One major limitation is that scientists currently lack direct tools to measure quantum entanglement inside solid materials. Hopefully, further research will overcome this long-standing challenge.

The study is published in the journal Nature Physics.