The Sula Sgeir gannet hunt, or “guga hunt,” is a centuries-old Scottish tradition where men from Ness (Isle of Lewis) sail to the uninhabited island of Sula Sgeir in August to harvest young gannets (guga) for food, a practice licensed by NatureScot and considered culturally significant, though animal welfare groups call it cruel and argue it’s unsustainable. Alice Millar Thompson reports.

A plume of smoke rises from the remote Scottish island of Sula Sgeir. The smell of burning feathers and butchery fills the air. The Men of Ness have had their hunt for the first time since 2021.

The annual Guga Hunt – the mass slaughter of juvenile gannets – has resumed, following a three-year hiatus due to the avian flu epidemic. The hunt is thought to have originated in the 15th century due to food scarcity on the Isle of Lewis during winter months, though it has endured well into the 21st century under the guise of tradition.

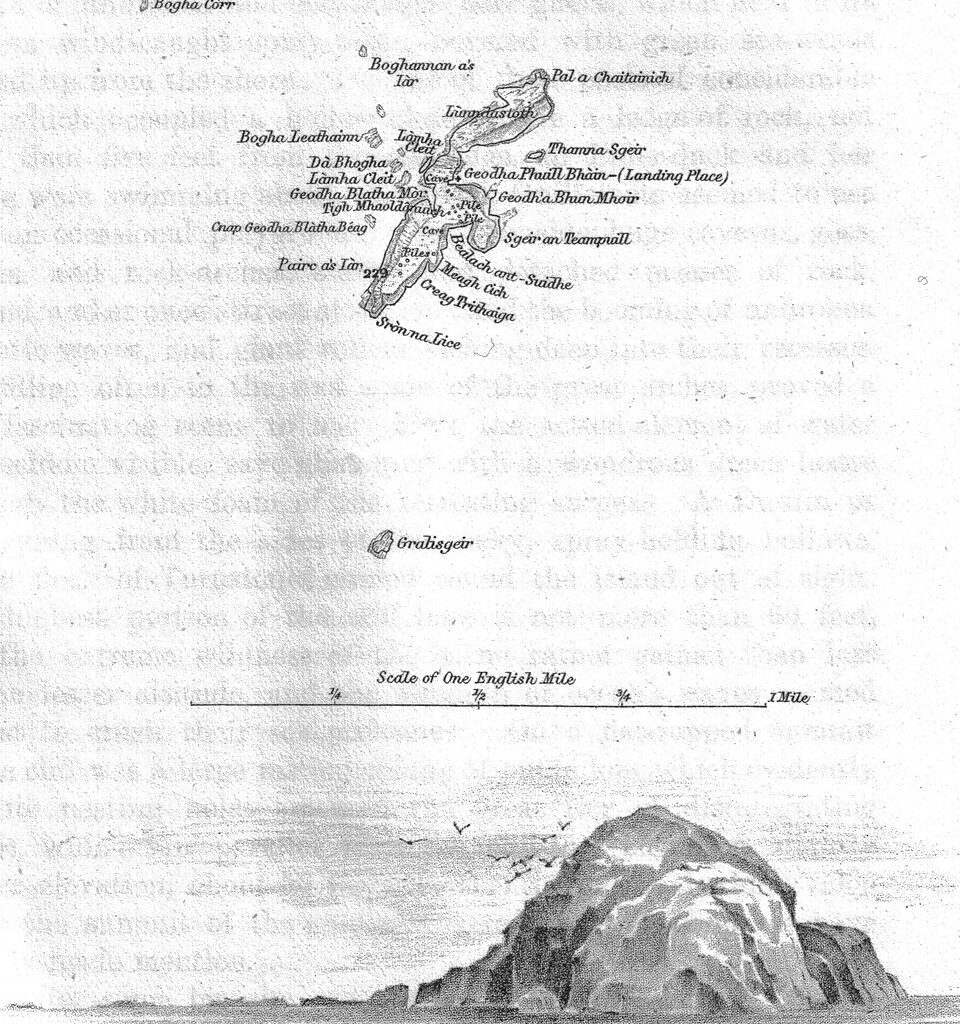

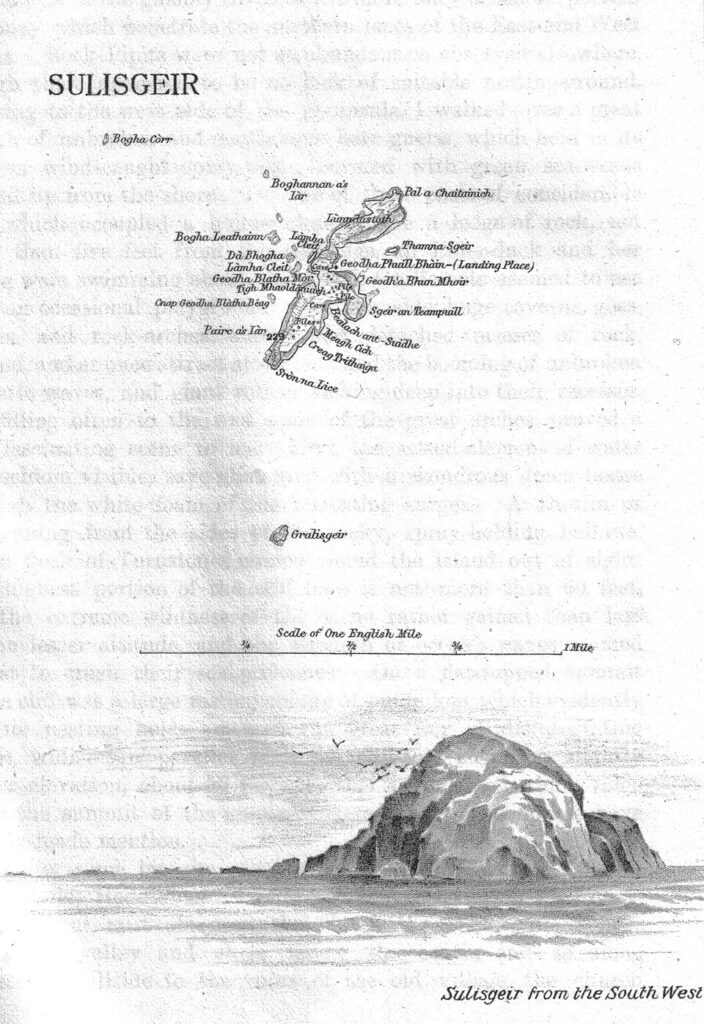

Sula Sgeir is a narrow, rocky reef that lies 38 miles from the northernmost point of Lewis, amid the hostile waters of the North Atlantic. Yet for centuries, it has been a fertile refuge for seabirds, to such an extent that its Scots Gaelic name translates as “gannet skerry”.

There are an estimated 10,200 breeding pairs of northern gannets currently living on the island, though the impact of avian flu on the colony has been devastating. The RSPB reported that its population dropped by 23% between 2021 and 2023, and though Sheila Voas, the Scottish Government’s chief veterinary officer, says that the species as a whole appears to be developing a “degree of immunity,” the colony has not yet made a full recovery.

On Sula Sgeir, gannets have few natural predators: a vulnerability that has long been exploited by hunters. Guga meat comes from juveniles killed during a specific two-week period in their lifespan, while they are still unable to fly, and is now considered a delicacy rather than a necessity.

However, the methods of capture and slaughter have not changed in centuries and remain a controversial feature of the practice. One hunter uses a 10ft-long long pole with either a noose or metal jaws on one end to pull young birds from their nests by the neck, before handing them to their partner, who bludgeons them to death. This has been heavily criticised by Protect the Wild, and Charlotte Smith, the organisation’s lead on hunting campaigns, states: “The method of killing chicks has been recognised as inhumane and barbaric by leading animal welfare organisations, such as the Scottish SPCA.”

The island is designated a Special Protection Area (SPA) however, Section 16 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, enables NatureScot to issue annual licenses to the hunters. In August of 2025, the “Men of Ness” were permitted to take 500 birds, which were reportedly sold for £35 each at Port of Ness. While this marks a reduction from the culls of 2,000 sanctioned in previous years, northern gannets remain on the amber list of conservation concern, and the decision has been widely criticised by charities such as the RSPB and Scottish Seabird Centre.

This is partially due to concerns around NatureScot’s methods of population monitoring and failures to correctly enforce their own regulations. Charlotte Smith from Protect the Wild said, “There are serious weaknesses in how conservation laws are enforced, issuing licenses based on incomplete science being one,” highlighting the continued licensing of the hunt, despite the hunters’ failure to report important details, such as the method of slaughter.

An RSPB spokesperson said: “We have called on NatureScot to pause the granting of licences to hunt on Sula Sgeir until there is clear evidence of population recovery to pre-HPAI levels and until the risk level for the disease amongst wild birds is assessed as ‘Medium’ at most.” The organisation has requested that more thorough investigations be carried out using drone surveys as an alternative to the current method of computer modelling, though it has yet to receive a response from NatureScot.

Gannets reach maturity between the ages of four and seven years old, and each pair only produces one chick per year, meaning that colonies are slow to recover from any sudden loss. Protect the Wild argues that the population on Sula Sgeir has long been suppressed by the Guga Hunt and has tirelessly campaigned to show the inherent cruelty of the practice. “Gannets have really strong bonds and they are intelligent birds, but the parents can’t do anything to save their chicks,” Charlotte Smith explained, “They’re just very vulnerable animals.”

The men perch on the edge of the cliff face amid a flurry of downy, white feathers. The carcasses have been plucked, singed, scrubbed, gutted, salted, and arranged in a concentric pile, which forms a gruesome companion to the cairns left behind by generations of hunters before them. In previous centuries, islanders of all ages worked together to stockpile meat for the winter, but attitudes have shifted.

The community is no longer reliant on guga meat for survival and younger generations are increasingly aware of the impacts their actions have on the environment. Amid the ageing populations of remote communities such as Ness, the growing number of short-term holiday lets, and the erosion of the Gaelic language, anxieties have risen around the preservation of cultural heritage. In response to this, Charlotte Smith of Protect the Wild said: “Tradition alone cannot justify cruelty or ecological harm. There have been many historic practices, like bear fighting, that were once defended as heritage, yet societies rightly ended them. I think we can still honour cultural heritage without having animal cruelty involved.”

“People across Europe and the rest of the world come to Scotland to see these seabirds alive. Gannets enrich Scotland’s natural heritage,” said Smith. Wildlife forms an important part of coastal tourism and the image of the northern gannet – with its yellow cap and ethereal blue eyes, diving arrow-like into frigid waters – has become emblematic of the country’s wild spaces.

Avian flu remains a threat, and scientists have warned that changes to migratory patterns caused by climate change may increase the risk of disease transmission globally. The Scottish Government’s animal health and welfare team has measures in place for this eventually, to identify and mitigate the spread of emerging diseases among both wild birds and livestock. “We do international disease monitoring, so we can spot trends,” Sheila Voas said. “We speak to ornithologists about what’s happening with migration to understand whether we’re at peak migration and whether there’s anything unusual.”

As climate change accelerates and human activity intensifies in their habitats, gannets face increasing pressures. Overfishing has depleted stocks of haddock, anchovies, and sardines, upon which gannets are reliant, and offshore developments such as windfarms and oil extraction encroach on feeding grounds, causing food scarcity. It is possible that, in the coming years, the species will experience a further decline. We need to be prepared to adapt, in order to reverse the damage we have caused as a species, and accept that some traditions must be consigned to history out of necessity.

A survey commissioned by Protect the Wild revealed that 69% of the public are in favour of a ban on the Guga Hunt, and as of December 2025, a Scottish Parliament petition with over 21,000 signatures is under consideration.