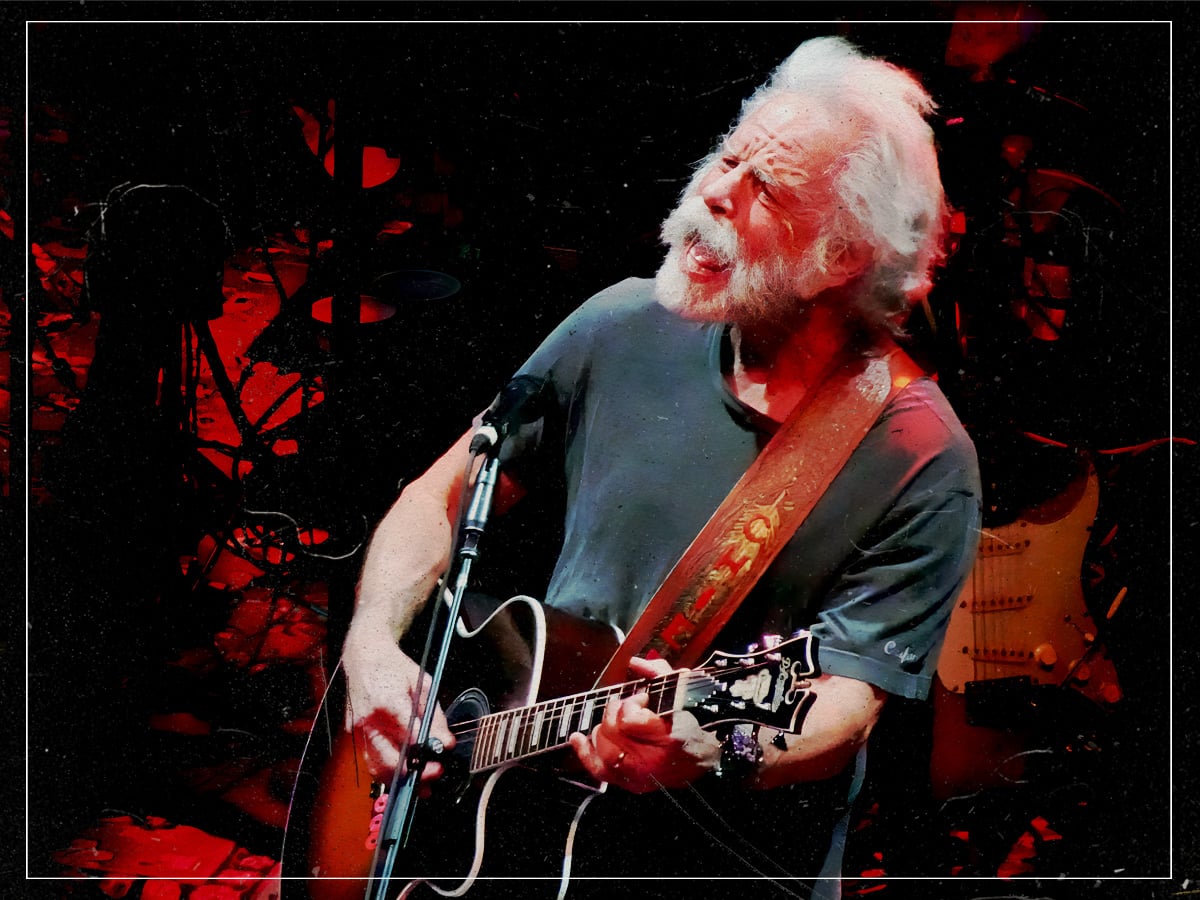

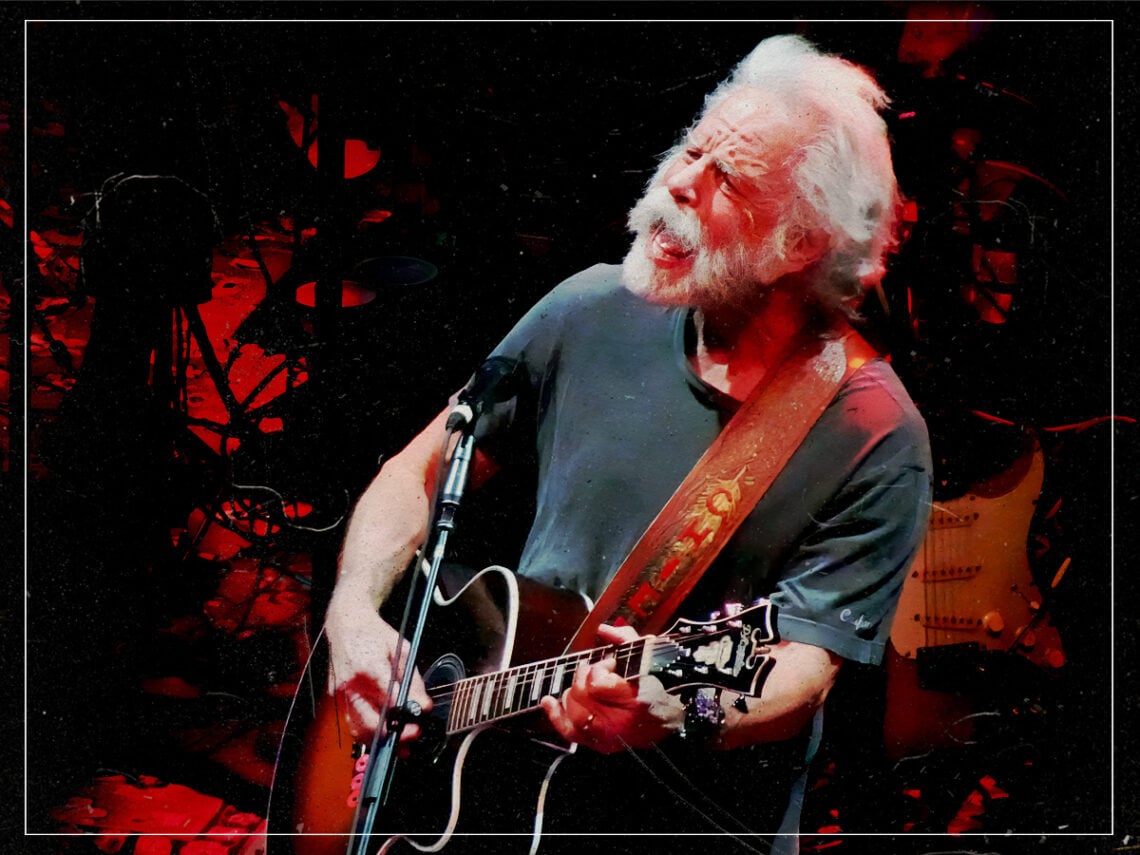

(Credits: Far Out / Thekingdekalb)

Wed 31 December 2025 21:30, UK

Rhythm guitarist Bob Weir is just as essential to the Grateful Dead story as their de facto captain, Jerry Garcia.

The two had years to hone their musical alchemy. But a 16-year-old, when first meeting Garcia on New Year’s Eve 1963, an impromptu jam that evening resulted in the two forming predecessor outfits Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions and The Warlocks and winning regional fame, before settling on the Grateful Dead for their show at one of Ken Kesey’s famous Acid Test parties in December the following year.

A curious brew of styles was conjured from Weir and the gang. While soaking up the LSD expanses on offer amid the West Coast underground, Grateful Dead coated their rock stroll with lashings of psychedelic glimmer yet stolidly anchored to Americana’s musical sediments. Jazz, blues, country, and a little folk all swirled around their sound, gliding from the Summer of Love’s pop lysergia to the earthy roots revivalism with barely a Deadhead fan noticing.

It took a guitarist with serious chops to keep up with Garcia’s dextrous lead, as well as the Grateful Dead’s signature penchant for improvising their repertoire indefinitely toward entirely new compositional forms, a habit beloved by their devoted fanbase while leaving their punk detractors deathly cold. Still, whatever you think of their blues noodles, Weir’s formative influences certainly offered an intriguing window into just where ‘The Other One’ writer found his fluid and free-form stylings.

“Initially, country and acoustic blues players,” he told journalist Alan Paul in 2015. “But my dirty little secret is that I learned by trying to imitate a piano. Specifically, the work of McCoy Tyner in the John Coltrane Quartet. That caught my ear and lit my flame when I was 17.”

He added, “I just loved what he did underneath Coltrane. So I sat with it for a long time and really tried to absorb it. Of course, Jerry was very influenced by horn players, including Coltrane. But I never really explicitly thought about that relationship. Because I didn’t really ever decide to pattern myself after McCoy Tyner’s piano. It just grabbed me.”

Jazz perhaps centres on Weir’s rhythmic touch as the essential element across his playing. One listen to any of Tyner’s powerful but percolating piano drops across his work with Coltrane and the vast Blue Note roster points to Weir’s internal note-taking, the old NEA Jazz Master able to explore nebulous expanse while always keeping an eye on any given piece’s base form. It’s a trick that would serve Weir well for decades.

Tyner’s loose cohesiveness in his approach would also guide Weir’s embrace of ensuring some space, be it on stage or in the studio, for Garcia’s soloing intuitions to soar when necessary, all indirectly nurtured by Tyner’s pioneering jazz magic.

“I had to figure out something else to do, and back in those days playing rhythm guitar was a pretty functionary kind of deal; there wasn’t a lot to it,” Weir revealed to Dan Rather in 2015. “There weren’t any examples of people for me to pattern what I was doing after, so I went for piano players.”

Related Topics