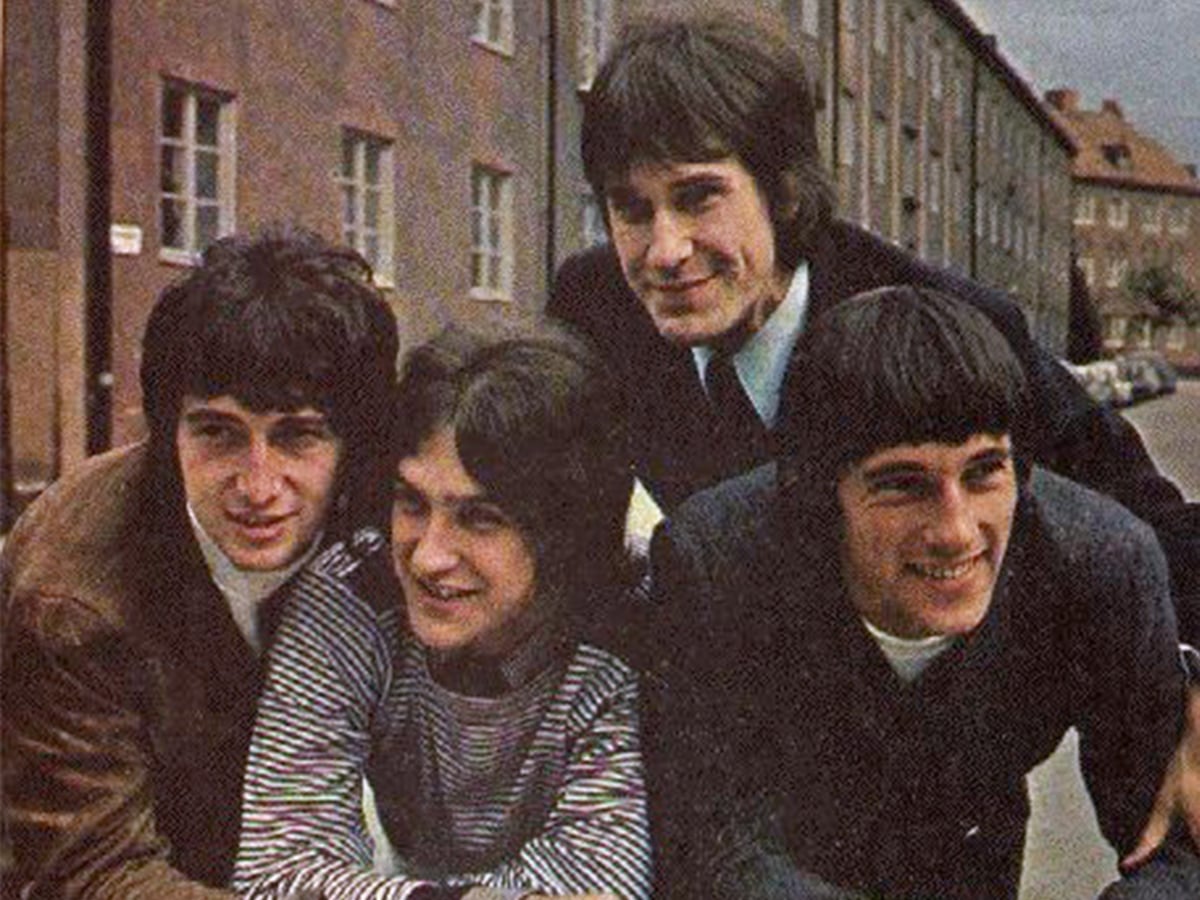

(Credits: Far Out / Public Domain)

Thu 1 January 2026 1:00, UK

“I never knowingly sat down and said I’m going to write kitchen-sink music,” Ray Davies told The Independent in 1994. “I just wrote about normal, everyday people, their hopes and fears.”

When Davies first started crafting his unique, working-class character studies on early Kinks records in the mid-1960s, he wasn’t necessarily alone in his pursuit. The Beatles, The Who, and dozens of other bands were venturing into this lyrical territory, similarly inspired by the so-called “kitchen sink” realism going on in British theatre, film, and literature at the time.

What ultimately separated the Kinks from their contemporaries was Ray Davies’ determination to explore this type of storytelling with increasing empathy and interest into the late 1960s, long after a lot of the other leading songwriters of his generation had shifted their focus to drugs, peace, love, and revolution. Ray was as intrigued by these big ideas as anybody, but his feet remained firmly on the ground, cynically aware that no grand cultural shifts were going to succeed if a large portion of the population was still living a hopeless existence.

“I think if The Beatles had done ‘Dead End Street’ it would have been through rose-tinted glasses,” Ray Davies told Classic Rock in 2022, referring to one of the Kinks’ defining singles, released in 1966.

‘Dead End Street’ was arguably the dividing line between the first phase of the Kinks’ career – the groundbreaking, distortion-assisted rock hits ‘You Really Got Me’ and ‘All Day and All of the Night’ – and what would become more of their legacy as a high-concept art band, concerned with culture, real-world characters, and societal injustices.

“It was written very quickly and it was written for the winter,” Ray Davies recalled, noting that ‘Dead End Street’ was recorded in October and released a month later in November of ‘66. “It was that thing of living in England and having had a great summer and now the light was closing in and the mood just shifts. The music had that little jazz backbeat, but there were these dark edges.”

As one of England’s most successful bands, riding high at the height of swinging London, it wasn’t exactly par for the course to write a retro-inflected tune about a working class couple struggling to make ends meet, but this is ultimately what made the Kinks one of the most influential and important bands of their era, even if it probably reduced their mainstream appeal worldwide at the time.

“What are we living for?” Davies sings. “Two-roomed apartment on the second floor / No money coming in / The rent collector’s knocking, trying to get in / We are strictly second class / And we don’t understand.”

The first recording of ‘Dead End Street’ was actually close to the “rose-tinted” version Davies wanted to avoid, as producer Shel Talmy had softened its tone with a French horn and a Hammond organ. When Talmy left the studio for the evening, though, Davies and his bandmates decided to take a second run at the song themselves, swapping the organ for a punchy piano and – if you believe Davies – replacing the French horn with a trombone played by a local musician they’d plucked out of the nearest pub.

Many years later, in an interview with Q magazine, Davies explained how ‘Dead End Street’ served as something of a reality check for the more romantic narratives coming out of London at the time.

“My whole feeling about the ’60s was that it’s not as great as everyone thinks it is,” he said. “Carnaby Street, everybody looking happy, that was all a camouflage. That’s what Dead End Street was about.”

Related Topics