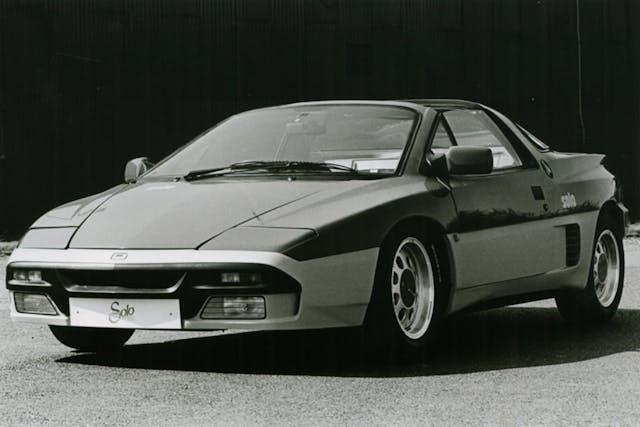

It was, in that Great British Tradition, a heroic failure, but the Panther Solo 2 had almost all the right ingredients to rival the best supercars of its day.

When it debuted in 1989, Car magazine declared it, “The most important British sports car since the E-type Jaguar.”

Behind it was plucky Panther, a company previously known for making the very retro Kallista—a sort of cut-price Morgan. Korean owner Young Chull Kim, who had rescued the company from bankruptcy, no longer wanted to look backwards. A new Panther would have its eyes firmly on the future.

Panther

Panther

The Solo project was originally conceived as an affordable, lightweight, mid-engined, rear-drive sports car. A concept featured Fiero-like bodywork by Ken Greenley, tutor of automotive design at London’s Royal College of Art, while the car’s chassis was the job of Len Bailey, who had previously worked on the likes of the Ford GT40 and GT70 with Alan Mann Racing. The car made its debut at the British Motor Show in 1984, and all was going well until Kim had the opportunity to drive Toyota’s then-new MR2 and realized that the Solo simply couldn’t compete with the Japanese giant’s sportster.

It was back to the drawing board, but now with an even bigger ambition. If Panther couldn’t rival Toyota, maybe it could take on the likes of Porsche instead.

The same team reassembled, and over the next three years, the Solo 2 took form. Greenley was given carte blanche with the design, which grew in length to accommodate a pair of rear seats, while soft lines took the place of the original Solo’s creases. Pop-up headlamps were replaced with lenses behind rotating covers to maintain daytime wind-cheating capability. The car’s aerodynamics were incredibly advanced, honed with the help of a Formula 1 team. According to the Solo’s launch kit, “The shape Ken arrived at, with the help of March Engineering, generated positive downforce at both ends of the car, and wind tunnel tests indicated a 33 lb front downforce and 82 lb rear downforce at 150 mph.”

Panther

Panther

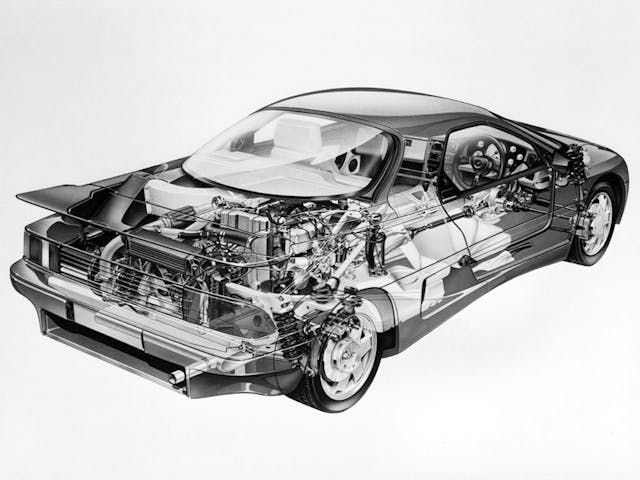

Even more innovative was the Solo 2’s structure. A central steel spaceframe supported the bodywork made from aerospace-style aluminum honeycomb sandwiched between epoxy-bonded fiberglass. In the front, a crushable structure, similar to that used in the day’s F1 cars, would enable the Solo 2 to meet worldwide crash regulations, including those in the U.S. Ambitious, indeed.

Suspension was all independent, and, unusually, no anti-roll bars were fitted. Panther’s reasoning was that the combination of the cars’ low center of gravity and its relatively high roll stiffness rendered them unnecessary.

“I remember best a day at Castle Combe with a load of other good and fast cars from some pretty established and illustrious companies,” recalled Andrew Frankel, writing for Goodwood. “And as a thing to drive, the Solo beat them hollow. It rode Combe’s notorious bumps with imperious aplomb and its steering was a good as any car’s I’d driven.”

To endeavor to give the Solo 2 the speed to suit its sublime handling, Panther turned to the Ford Sierra RS Cosworth and its two-liter 200-hp turbocharged four-cylinder engine. For traction, Panther opted for all-wheel drive (three years before Ford offered a similar setup in the Cossie), which required an in-house central transfer system and Ferguson center differential. The torque split was rear-biased with just 34% going to the front wheels, and a Borg-Warner T5 manual transmission took care of gear selection.

That all sounds great on paper—something similar certainly worked for the Group B Ford RS200—but the Solo 2 was supposed to be more sophisticated than the rally rocket. The engine “sounded like a bag of bolts being poured into a blender,” noted Frankel. “Did I mention that with so little power it was rather slow too? In fact, all it really had going for it was its chassis.”

The engine “lacks pedigree and power,” agreed Car’s Gavin Green. The Solo 2, he wrote, was “brilliant in patches, mediocre in other areas, it is a car that cries out for more development. It needs another year, probably two before it can be a serious challenger. The potential, the enthusiasm is there. But the one thing the Solo has run out of is time. We’ve waited long enough.”

Having followed the Panther’s progress in the pages of Britain’s motoring magazines from the start, I vividly remember reading this review, which compared the Solo 2 to the Lotus Esprit SE, and I too was disappointed that this British underdog would never take the fight to more established supercars at home and abroad.

Panther did receive an initial 125 orders for the Solo 2, but customers, tired of waiting during an increasingly protracted development process, and disheartened by the motoring media’s U-turn on its enthusiasm, soon began to cancel. In the end, it’s believed that only 13 cars were actually delivered.

Back in 1990, Autocar summed the Solo up best. “[Panther] must be one of the smallest manufacturers in the world yet it has produced a car with more flair, innovation and design integrity than most massive corporations ever show. It’s rivals, all technically better cars, will be around long after the Solo has died. And that’s the shame because, of them all, it is the Solo that shows the way forward.”

Panther

Panther