The European Union has completed a review of its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) after a two‑year transition period. The European Commission said that the policy has motivated more countries to adopt carbon pricing systems beyond Europe. The review also found that when CBAM begins to charge a carbon fee, it will have minimal impact on the world’s poorest countries.

The findings come as the mechanism prepares to start charging fees in January 2026 and proposes several changes to include certain downstream products.

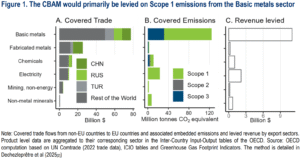

CBAM is a climate policy that applies a carbon price to certain imported goods that carry high greenhouse gas emissions. The goal is to create fairness for EU producers. They must follow the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS). This also aims to cut down on carbon leakage, which is when production shifts to countries with looser climate rules.

What the Review Says About Carbon Pricing

According to the Commission’s review, CBAM has spurred interest in carbon pricing in other countries. Firms and governments outside the EU are talking more about carbon pricing. They want to measure and report emissions better. This trend suggests that CBAM is serving not only as a tariff on emissions but also as an incentive to adopt carbon pricing tools more widely.

The review assessed CBAM’s transition phase from 2023 to 2025. During this time, companies provided data on the emissions embedded in their goods imported to the EU. This data collection period helped build capacity for the full operational phase.

Starting in 2026, importers must purchase CBAM certificates that reflect the carbon price paid under the EU ETS or pay the equivalent fee. The two-year run-in period helped companies outside the EU adjust their reporting systems. They also learned about compliance requirements before fees started.

Minimal Impact on World’s Poorest Countries

One key finding of the review is that the impact on the world’s poorest countries will be limited once CBAM starts charging a carbon fee. The Commission’s assessment shows that many least developed countries don’t export a lot of CBAM-covered goods. As a result, the mechanism will not directly impose large carbon fees on them.

Many low-income countries don’t produce much high-emission stuff, like steel, aluminum, cement, fertilizers, or electricity. These are the products that CBAM first targets. Because of this, exporters from these nations are less exposed to carbon fees than those from more industrialized countries.

At the same time, the EU has acknowledged concerns from some developing nations. The Commission has urged the use of development funds and technical help. This will assist affected countries in decarbonising and lowering future carbon fees.

Some funding might come from the EU’s large development budget. This money will support clean technologies and energy systems in partner countries.

How the Carbon Border Mechanism Works

CBAM is intended to protect EU industries that already pay for carbon emissions under the ETS. Without a border adjustment, imported goods might be cheaper. If these goods don’t face similar costs abroad, they could hurt the EU’s climate policies.

- The mechanism adjusts import costs so that carbon costs are similar for EU and non‑EU products.

Starting January 2026, importers must report emissions data. They also need to buy carbon certificates for the emissions in their products. Fees will reflect the difference between the carbon price paid in the country of origin and the EU ETS price. The measure covers goods such as steel, aluminium, cement, fertilizers, electricity, and hydrogen.

These carbon fees are expected to generate revenue for the EU budget, which regulators see as a tool to support further climate action. One estimate suggests that CBAM could generate around €2.1 billion in revenue by 2030 as the scope widens and payment obligations rise.

Proposed Changes: Downstream Goods in Focus

Alongside the review, the Commission has proposed changes to strengthen and expand CBAM. One major proposal targets goods further downstream in global value chains. This means products that are not raw materials but contain high shares (79%) of steel and aluminium. These could include machinery, automotive parts, household appliances, and construction equipment.

The Commission’s proposal would add around 180 new product categories to the list, potentially covering thousands of importers.

The aim of this expansion is to avoid carbon costs by simply shifting to other stages of production. Without this extension, some manufacturing may shift. This could happen to avoid carbon fees on raw materials after they become part of finished products.

The Commission also plans anti‑circumvention measures to ensure that importers cannot avoid fees by misreporting emissions. These rules are designed to require stricter reporting and sometimes use default country emissions values if actual data is missing or unreliable.

Further reforms aim to help companies adjust and ensure fair competition. These include simplifying reporting procedures and clarifying the calculation of emissions embedded in goods.

The proposed changes reflect feedback from industry and trading partners collected during the transition.

Notably, the European Commission also started a Temporary Decarbonisation Fund. This fund helps EU producers of CBAM-covered goods. It aims to offset competitiveness losses in markets outside the EU. The EC noted that financing will come:

“…from member state contributions, constituting 25% of revenues from CBAM certificate sales in 2026 and 2027, while the remaining 75% will be an EU Own Resource.”

Pushback, Policy Debate, and Trade Tensions

Responses to the CBAM and its reforms vary. Some industry groups want more support to stay competitive. This is especially true for downstream products. These products were not initially covered but now face carbon-related cost pressures.

Others warn that some loopholes remain or that the mechanism may not fully prevent carbon leakage.

Critics argue that parts of the proposed reforms may cater too closely to heavy industry demands, weakening climate impact. They highlight concerns about temporary funds and exemptions that could help EU exporters without strong environmental requirements. Such measures, they say, risk diluting CBAM’s core climate objective.

For instance, even with the expanded product list, the carbon levy will only boost emission cuts by 0.6% to 2%, per the Commission’s CBAM review report. Most savings—38.3 million tonnes of CO₂ by 2030—come from the original CBAM design, without downstream products.

At the same time, many trading partners have expressed concerns about CBAM’s implications for global trade. Some large economies, including China, India, and Brazil, have criticised the mechanism as potentially burdensome or protectionist.

The EU has emphasised that CBAM is a climate policy, not a trade barrier, and that it aligns with World Trade Organization (WTO) rules.

Despite these debates, global interest in border carbon adjustments is growing. Several countries and regions are studying similar carbon pricing tools as part of climate strategies.

What Comes Next for CBAM? From Transition to Full Enforcement

CBAM enters full operational status on 1 January 2026. Importers must begin submitting required data and prepare to pay carbon fees for the first time for goods entering the EU. The revenue and climate enforcement tools tied to CBAM will develop as implementation proceeds and as extensions to more product categories are adopted.

The Commission plans ongoing evaluations of CBAM’s design and impact. Later reviews could explore including indirect emissions or extending coverage to additional sectors such as chemicals. These future steps are meant to strengthen the link between carbon pricing, trade, and global decarbonization.