Initial superradiant decay and spectral hole

For all experiments, we use the previously established protocol34 for generating a uniformly inverted spin state. All NV− spins are tuned into resonance with the cavity, using a static magnetic field with equal projections along the four diamond axes. We apply a microwave inversion pulse to homogeneously invert all spins from a relaxed initial state of the effective two-level systems. Subsequently, we rapidly detune the spin ensemble from the cavity resonance and store the inversion for a set hold time. This procedure allows for the preparation of states with uniform initial spin inversion \({p}_{0}=\langle {\sigma }_{j}^{z}\rangle\) and almost-zero transversal spin components \(\langle {\sigma }_{j}^{-}\rangle \approx 0\). The values for p0, bounded by ±1, are tunable within the range of 0.1–0.4 by modifying the hold time on the order of milliseconds.

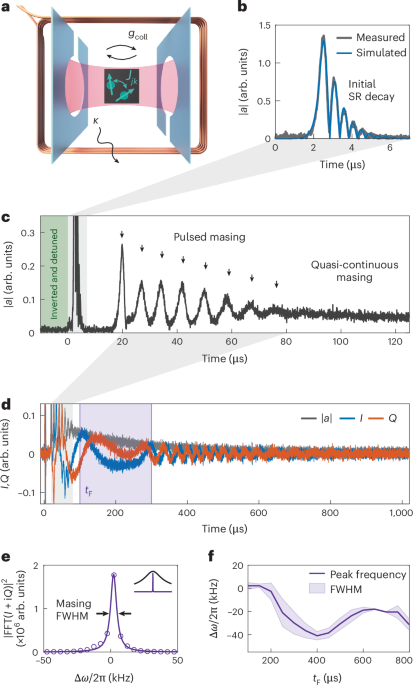

On tuning the spins back into resonance with the cavity using the detuning loop, the inverted spin state is free to interact with the cavity mode. If the stored inversion exceeds the threshold p0C > 1, the system enters a metastable state35. Here \(C={g}_{{\rm{coll}}}^{2}/\kappa \varGamma \approx 14.6\) is the cooperativity, a dimensionless parameter combining the collective coupling strength gcoll/2π = 4.53 MHz, the cavity linewidth κ/2π = 418 kHz (half-width at half-maximum) and the effective ensemble dephasing rate Γ/2π = 3.36 MHz. The latter accounts for both inhomogeneously broadened spin frequency distribution ρ(ω), with a full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of W/2π = 8.65 MHz, and the spin linewidths modelled by γ⊥/2π = 179 kHz (equations (9) and (10)).

In this metastable inverted state with p0C > 1, any fluctuation will stimulate a collective emission process known as a superradiant decay36. Conversely, if the inversion is below the instability threshold, dephasing due to inhomogeneous broadening becomes dominant and prevents this avalanche process35. In our case, the superradiant decay is triggered by noise photons from the input line. As the spin decay accelerates, the cavity amplitude ∣a∣ increases. It reaches its maximum as the collective spin vector points towards the equator of the Bloch sphere, where the cavity amplitude \(\max (| a| )\propto {p}_{0}-1/C\) serves as a measure of the initial inversion above threshold (equation (12)), and the emitted intensity \(| a{| }^{2} \approx {({p}_{0}N)}^{2}\) exhibits the characteristic quadratic scaling of superradiance with the number of effectively participating spins2,34. Subsequently, energy is coherently exchanged between cavity and spins, visible as damped Rabi oscillations (Fig. 1b). This coherent exchange is eventually stopped by coherence-limiting processes in the system, mainly the dephasing of inhomogeneously broadened spins.

Crucially, the cavity-resonant spins—which dominate the collective emission dynamics—become de-excited through superradiant emission, whereas the off-resonant spins maintain their inversion. This leaves behind a spectral hole37, a region of depleted inversion centred at the cavity frequency. This initial superradiant decay dynamics is well captured by the Maxwell–Bloch equations38 that provide a semiclassical description of the collective coupling between a non-interacting spin ensemble and the cavity mode. This standard picture does not predict further dynamics beyond the initial emission pulse, once the resonant spin inversion has been sufficiently depleted below the threshold p(Δ = 0) < 1/C (equation (11)).

Pulsed and quasi-continuous masing

Surprisingly, however, we observe a train of masing pulses that emerges at about Δt ≈ 15 μs after the initial superradiant burst (Fig. 1c). This behaviour cannot be understood within the standard semiclassical theory for emitter ensembles in cavities38 and suggests a dynamical refilling of the spectral hole burned by the collective cavity emission. The timescale for the revival pulses appears unexpectedly long, greatly exceeding the characteristic timescales of the cavity loss rate κ−1, the effective ensemble dephasing Γ−1, the collective cavity coupling \({g}_{{\rm{coll}}}^{\;-1}\) and the spin decoherence \({\gamma }_{\perp }^{-1}\). This clearly excludes Rabi oscillations or spin-echo effects as potential explanations39 for the observed superradiant pulse trains.

The masing pulses appear as distinct Gaussian-like peaks in the cavity amplitude with progressively increasing FWHM values ranging from around 1.5 μs to 3.8 μs. Each pulse has a random but nearly constant phase, as determined from the quadratures I and Q of the cavity amplitude, corresponding to coherent pulsed masing with near-transform-limited FWHM bandwidths ranging from around 400 kHz to 120 kHz. Following the early sequence of discrete pulses, the emission evolves into a quasi-continuous regime that persists for up to 1 ms.

The extended cavity dynamics (Fig. 1d) is measured using the same system parameters as those in Fig. 1c, but at half the digitizer sample rate in the heterodyne detection chain. The recorded quadratures I and Q of the cavity amplitude are demodulated at an intermediate frequency of 5 MHz detuned from the cavity resonance. We extract the emission’s linewidth by using fast Fourier transform analysis and Lorentzian profile fitting within the integration window of 200 μs (Fig. 1e). Shifting the start of the integration window tF, we analyse (Fig. 1f) how the central frequency of the masing emission drifts over time within ±25 kHz. The observed linewidth, varying from 5 kHz to 20 kHz, is two orders of magnitude below the cavity linewidth κ and the individual spin linewidth γ⊥, highlighting the crucial role of collective enhancement—an indicative trait of superradiance—in achieving high coherence. We attribute the linewidth variation to the emission frequency drift within the integration window caused by magnetic field oscillations after rapidly switching the detuning loop. These oscillations appear on a scale that is three orders of magnitude smaller than the full extent of the loop detuning of roughly 20 MHz.

Experimental evidence for spectral hole refilling

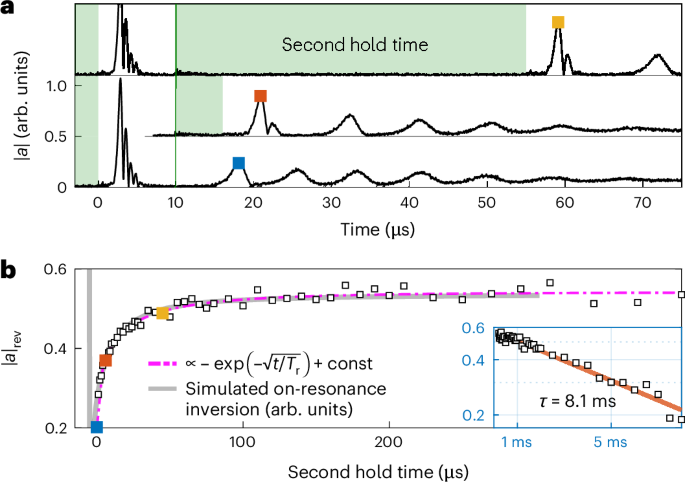

To identify the mechanism responsible for the apparent spectral hole refilling, we conduct a set of auxiliary measurements designed to decouple the dynamics within the spin system from the cavity. Right after the initial superradiant decay, we rapidly detune the spins and introduce a second hold time, during which the spin–cavity interaction is suppressed. Extending this isolation phase reveals that the amplitude of the first revival pulse increases with longer off-resonant hold times (Fig. 2a,b). This strong dependence on the isolation period clearly establishes that the cavity coupling plays no substantial role in the spectral hole refilling, which instead must be driven by another additional mechanism. When the spins are tuned back into resonance, the accumulated inversion inside the hole—now above the instability threshold—triggers a superradiant pulse, whose amplitude scales with the amount of resonant spin inversion, which initially increases with the hold time. At longer hold times, once the spectral hole is maximally refilled, the amplitude reaches a plateau (Fig. 2b). The eventual decrease in amplitude over longer timescales reflects a global loss of spin inversion, as previously discussed in ref. 34.

Fig. 2: Influence of second hold time on revival dynamics.

a, Stacked cavity signals of the superradiant dynamics with a second stabilization sequence (hold time), represented by the light-green shading. Increasing the duration of this second hold time extends the spectral hole-filling process, influencing the amplitude of the superradiant masing pulse revival. b, Revival amplitude ∣a∣rev for varying second hold times. An initial stretched exponential increase is followed by an exponential decrease for longer timescales (inset). The data points are well described by simulating the on-resonance inversion using the parameters employed in Fig. 3.

Additionally, in Extended Data Fig. 1, we closely reproduce the revival pulse dynamics by deliberately creating a spectral hole with a microwave pulse, confirming that the refilling mechanism operates independently of how the hole is initially formed. Although the observed pulsed masing bears resemblance to recently reported periodic superradiance in optically pumped spin systems40, our system operates in a fundamentally different regime: the pulses emerge spontaneously without any external pump, pointing to a self-induced mechanism originating within the spin ensemble.

Many-body dynamics through dipole–dipole interactions in an NV− ensemble

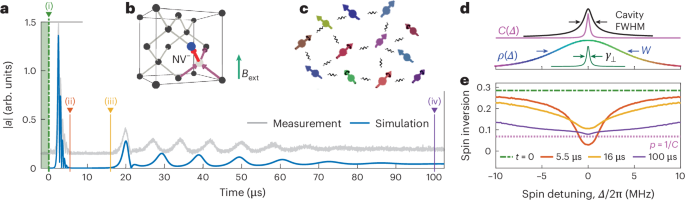

To understand and explain our experimental observations, we have performed microscopic simulations of the cavity-coupled spin ensemble in the presence of direct interactions between the emitters. As detailed in Supplementary Sections 1 and 2, the magnetic dipole interactions between the NV− centres generate a coherent exchange of spin excitations, which offers a possible mechanism for transporting inversion across the energy spectrum of the inhomogeneously broadened spin ensemble. The proper description of the collective spin–cavity coupling and the resulting superradiant emission dynamics requires sizable particle numbers to reliably sample the random positions, frequencies and orientations of the spins. Hence, we have implemented microscopic simulations of the resulting many-body dynamics for large numbers of ~106 particles, with randomly sampled positions rj in a cubic box to resemble our experimental NV− density, random cavity detunings Δj drawn from the known experimental spectrum ρ(Δ) (Fig. 3d) and randomly chosen spin orientations from one of the four possible directions for the tetrahedral symmetry of diamond (Fig. 3b). Noting that the single-spin decoherence rate γ⊥ exceeds the typical strength Jjk of pairwise dipole–dipole interactions, one can derive an effective rate description for the interaction-driven evolution of the spin inversion as

$${\partial }_{t}{p}_{j}=-\sum _{k}\frac{4{\gamma }_{\perp }| {J}_{jk}{| }^{2}}{{({{\mathit\varDelta }}_{j}-{{\mathit\varDelta }}_{k})}^{2}+4{\gamma }_{\perp }^{2}}\left({p}_{j}-{p}_{k}\right),$$

(1)

which, in turn, can strongly affect the many-body emission dynamics due to the collective cavity coupling. Equation (1) describes the transport of spin excitations across the sample and across the energy spectrum of the spin ensemble with a two-body rate ∣Jjk∣2 ∝ 1/∣rk − rj∣6 that is only effective for closely adjacent NV− centres.

Fig. 3: Simulation of superradiant dynamics driven by spin–spin interactions.

a, Simulation of the cavity amplitude ∣a∣ based on the microscopic spin model compared with the measurement (offset vertically for clarity), with four key time steps marked (as shown in e). b, NV− centre in a diamond unit cell, illustrating one of four possible alignments. c, Schematic of the simulated spin network: NV− centres are randomly distributed in space, orientation and resonance frequency, and interact via dipole–dipole couplings. d, Relevant linewidths in the hybrid system: cavity linewidth, inhomogeneous spin distribution of width W, single-spin dephasing rate γ⊥ and frequency-dependent cooperativity function C(Δ). e, Simulated spin inversion profiles at four key times: (i) at t = 0, uniform inversion; (ii) at t = 5.5 μs, deep spectral hole; (iii) at t = 16 μs, refilled above threshold; (iv) at t = 100 μs, broad, depleted quasi-steady state.

In Fig. 3, we show the simulation results for the spin–cavity dynamics in the presence of dipole–dipole interactions. We infer a starting inversion of p0 = 0.285 from the initial superradiant decay and set the typical nearest-neighbour NV− distance to r ≈ 7 nm to align the onset of pulsed masing with the experimental data, in good agreement with the independently estimated value of 8 nm based on the collective coupling strength and cavity mode volume (Methods).

The simulation quantitatively reproduces the dynamics up to the first revival pulse and qualitatively captures the key features of superradiant emission throughout the measurement interval, from the initial sequence of periodic pulses followed by the quasi-continuous masing regime. Although the precise spacing of the periodic pulses is not perfectly reproduced, the theory captures the characteristic shape of the masing pulses as well as their steadily increasing delay times.

To further corroborate the important role of dipole–dipole interactions, we also studied the refilling of the spectral hole in the absence of spin–cavity coupling, as measured experimentally (Fig. 2). We use the fact that the amplitude of a superradiant pulse directly results from the cavity-resonant spin inversion just before pulse onset (equation (12)). The measurement of ∣a∣rev (Fig. 2a), thus, provides direct access to the evolution of p(Δ = 0), and is shown as a function of the hold time (Fig. 2b). For comparison, we have simulated the spin dynamics, using the same parameters as employed in Fig. 3, but switching off the spin–cavity interaction after the initial superradiant decay. After accounting for a time offset between the initial decay and the first revival pulse, we find excellent agreement between experiment and theory, and observe that the hole refilling dynamics follow a stretched exponential:

$$p({\varDelta} =0)-{\overline{p}}\propto \exp (-\sqrt{t/{T}_{\rm{r}}}),$$

(2)

where \(\overline{p}\) is the average inversion of the ensemble. Fitting the revival pulse amplitude as a function of the second hold time yields a characteristic time constant Tr ≈ 11.6 μs (Fig. 2b). This behaviour is consistent with an independent measurement of the refilling time, obtained from the time delay Δt between the initial superradiant decay and the first revival pulse for different initial inversions p0 (Extended Data Fig. 2). The stretched exponential relaxation emerges from a simplified analytical solution to equation (1) (Supplementary Section 3). Importantly, the observed exponent of 1/2 (Extended Data Fig. 3) is a hallmark of the 1/r3 dependence of dipolar interactions32. We, thus, conclude that the dipole–dipole interactions between the spins are indeed responsible for the transfer of inversion with and without spin–cavity interactions.

On the basis of the above insights, we can now draw a conclusive picture of the observed superradiant masing dynamics. To this end, we show (Fig. 3e) the inversion profile at four key times during the measured and simulated dynamics. (i) All spins start fully inverted, well above the threshold. (ii) The initial superradiant decay generates a deep spectral hole around the cavity resonance, lowering the spin inversion below the threshold. Now, dipole–dipole interactions steadily repopulate the on-resonance spin inversion p(Δ = 0). (iii) The first revival pulse emerges after the refilled inversion crosses the instability threshold, triggered by residual cavity photons. Its amplitude reflects how much p(Δ = 0) has grown above the threshold. Following the simultaneous creation of the spectral hole, the refilling process starts anew. As more and more energy is emitted by the cavity, each subsequent pulse has fewer participating excited spins and, thus, generates a shallower hole, which leads to faster refilling. At the same time, the superradiant buildup gradually slows down, due to the 1/p scaling of the associated timescale41. As a result, the system transitions from an initial pulsed regime to a quasi-steady state (iv) in which energy is continuously replenished from the off-resonant spins, simultaneously being emitted through the cavity. This process eventually halts when the masing cannot be upheld due to considerable inversion loss.