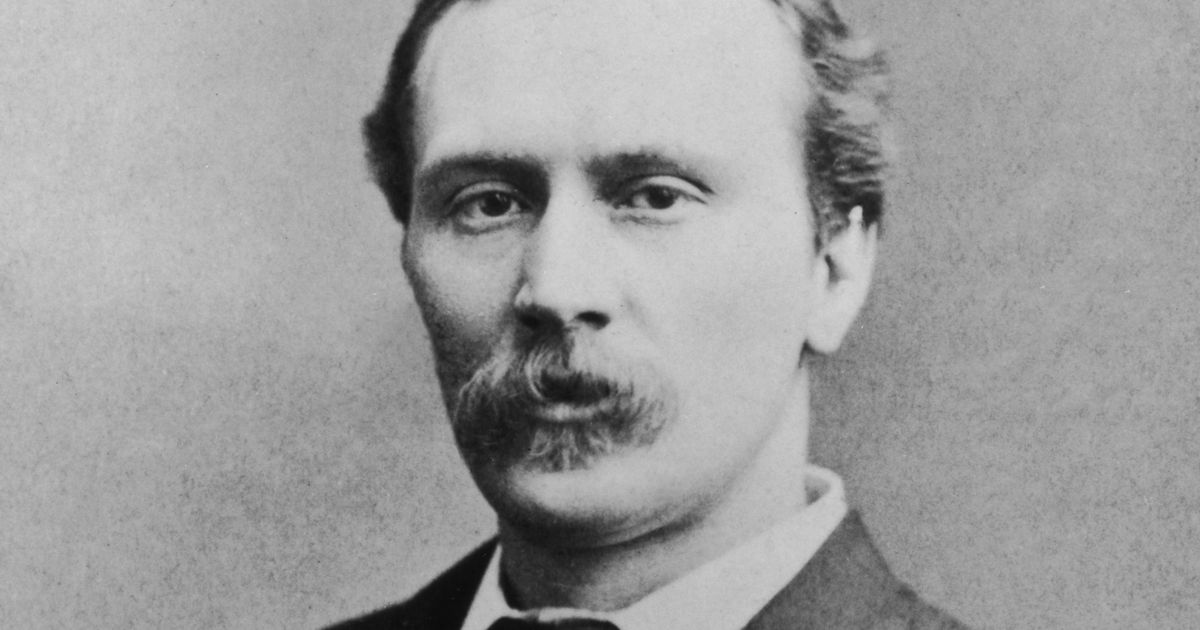

A diary and watch inscription confessing the murders have been linked to the cotton merchant Liverpool cotton merchant James Maybrick circa 1885(Image: Getty Images)

Liverpool cotton merchant James Maybrick circa 1885(Image: Getty Images)

A high profile history podcast recently revisited the terrifying tale of Jack the Ripper – the most famous serial killer cold case in British, and perhaps world, history. The Rest is history, hosted by historians Dominic Sandbrook and Tom Holland, took listeners through the historical context of the murders in 1880s London, delving into the clues, the victims and theories popularised by ‘Ripperologists’ still obsessed with solving the case 137 years later.

There are plenty of suspects for who might have been Jack the Ripper but through a dubious series of connections in recent decades, one Liverpool man emerged as an unlikely candidate.

Jack the Ripper killed at least five women in the Whitechapel area of London in a little over two months in 1888. The brutality of the killings and mutilations of the “canonical five” Ripper victims made the unknown murderer the first serial killer to receive global media attention.

In 1992, so-called Ripperologists thought they had finally found their man. Liverpool scrap metal merchant and freelance writer Michael Barrett approached London literary agent Doreen Montgomery on March 9, 1992, with what he claimed was the authentic diary of Jack the Ripper.

Mr Barrett claimed a family friend called Tony Devereux gave the diary to him in a Liverpool pub in 1991. The diary in question had many missing pages but described in detail the murders of the Ripper’s five known victims, along with confessions of a further two murders which allegedly took place in Manchester.

The anonymous diary, signed only as “Jack the Ripper”, was traced to a Liverpool cotton merchant by the name of James Maybrick. Though the diary’s author did not refer to himself by name, the names of family members and associates provided – along with his self-proclaimed nickname of “Sir Jim” – made it clear it was intended the reader should assume Maybrick was the author.

circa 1880: James Maybrick, the wealthy cotton merchant thought by some to have been Jack the Ripper. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)(Image: Getty Images)

circa 1880: James Maybrick, the wealthy cotton merchant thought by some to have been Jack the Ripper. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)(Image: Getty Images)

James Maybrick was born in Liverpool in 1838 to William and Susannah, and was the brother of popular singer-songwriter Michael Maybrick (an even more dubious Ripper suspect in his own right). After briefly working at a London shipbroking office, he moved to Virginia in the USA, then a thriving cotton port. As an Englishman abroad, it was here he allegedly adopted the nickname “Sir Jim”.

While in America, Maybrick contracted malaria, for which he was prescribed a medication containing arsenic and strychnine. Maybrick continued to use this medication for the remainder of his life, even after he began experiencing symptoms of poisoning.

Maybrick returned to Liverpool in 1880, meeting Southern belle Florence Chandler on the voyage and marrying her soon after. Chandler was 18 at the time, 24 years Maybrick’s junior, and despite producing two children their marriage was an unhappy one.

Both partners cheated on each other: Florence with cotton broker Alfred Brierley and James with several mistresses. When Maybrick died in 1889 of suspected arsenic poisoning, Florence was the prime suspect and spent 15 years in prison before being released when the case was reexamined and her guilt called into question.

The trial of Florence Maybrick was major news on both sides of the Atlantic at the time, and catapulted the family into the public consciousness. Her husband’s untimely death would also provide a convenient explanation for why Ripper murders ceased after only a few months when it seemed like the killer’s savage appetite was only growing.

August 1889: Florence Maybrick making her statement to the Liverpool Court during trial for the murder of her husband James Maybrick, the man thought to have been Jack the Ripper. Original Publication: The Graphic – pub. 1889 (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)(Image: Getty Images)

August 1889: Florence Maybrick making her statement to the Liverpool Court during trial for the murder of her husband James Maybrick, the man thought to have been Jack the Ripper. Original Publication: The Graphic – pub. 1889 (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)(Image: Getty Images)

The diary in question, dated to May 9, 1889, is a 9000-word justification for the Ripper’s crimes. The author – allegedly Maybrick – repeatedly refers to his wife as “the b****” or “the whore”, and lays plain his hatred of women in his targeting of London: “the City of Whores”.

The premise of Maybrick as the Ripper hinges on the connection between Liverpool’s Whitechapel and the London area of the same name. The author claims to “know for certain she has arranged a rondaveau (sic) with him in Whitechapel.”

Later, he adds: “I said Whitechapel it will be and Whitechapel it shall. The b**** and her whoring master will rue the day I first saw them together. I said I am clever, very clever. Whitechapel Liverpool, Whitechapel London – no one could possibly place it together.”

In the lurid text, the author engages in self-indulgent poetry glorifying the murders, which along with disturbing descriptions of mutilations and experiments with cannibalism breaks up the diatribe against Florence. The diary also lays out the author’s intention to scapegoat the East End’s Jewish population for the crimes he committed.

Despite the unlikely premise that Jack the Ripper’s true identity was that of a merchant from Liverpool, the diary was subject to expert analysis from 1992. In 1994, a team at the University of Leeds examined the paper and ink and found elements not present in many modern inks. None of the elements present contradicted the alleged age of the diary (1888-89), but neither was the alleged age confirmed.

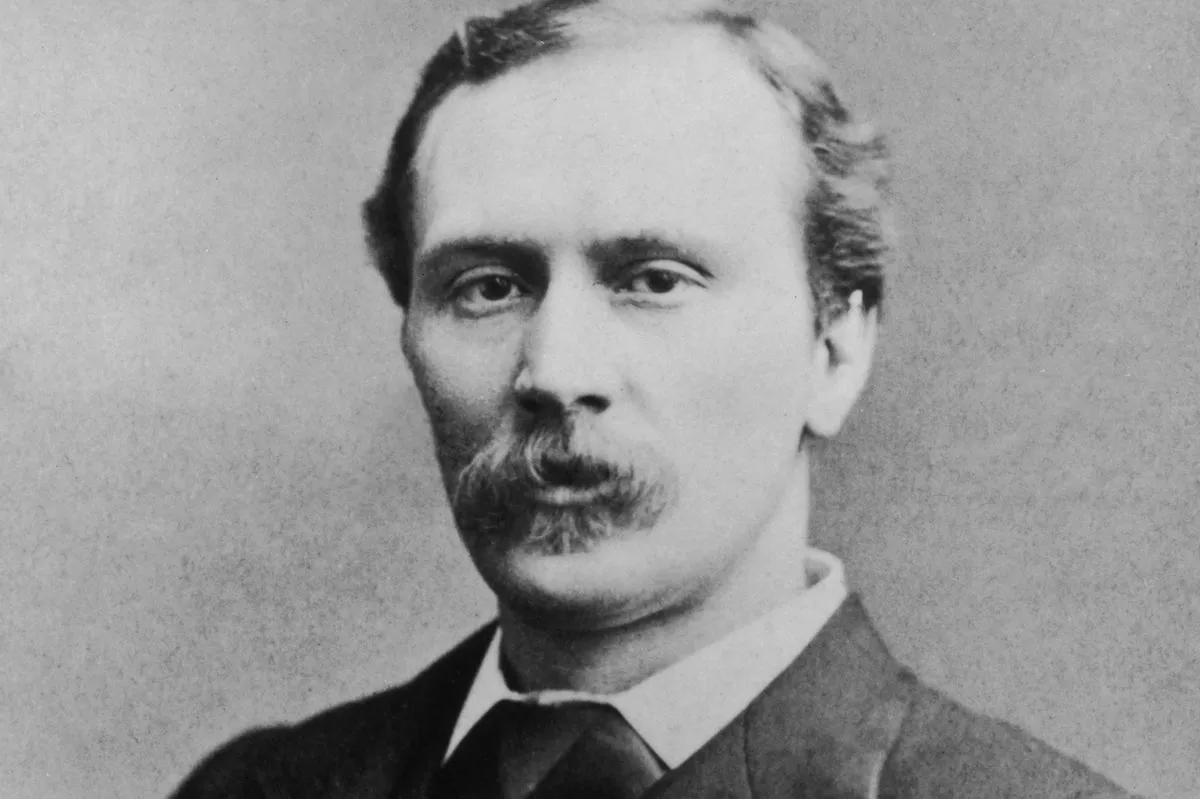

Cover of The Diary of Jack The Ripper: The Chilling Confessions of James Maybrick by Shirley Harrison. (Image: Liverpool Echo)

Cover of The Diary of Jack The Ripper: The Chilling Confessions of James Maybrick by Shirley Harrison. (Image: Liverpool Echo)

The diary was, however, written in a scrapbook, which American historical document specialist Kenneth Rendell noted in 1993 was completely unheard of for a Victorian diary. Other experts questioned the lack of similarity between the handwriting alleged to be Maybrick’s and handwriting present on letters from the time apparently penned by the Ripper.

Just as the authenticity of the diary was under scrutiny, a Liverpool security officer named Albert Johnson purchased an antique gold watch from Stewart’s in Wallasey. In June 1993, he claimed that two months earlier he had discovered scratchings on the watch which supported the case for Maybrick being the Ripper.

The etchings read: “I am Jack, J. Maybrick.” Accompanying Maybrick’s signature were the initials of the Ripper’s canonical five victims Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly.

The suspicious timing of this revelation brought plenty of scrutiny on Mr Johnson. Nevertheless, the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology published three reports from August 1993 to January 1994, examining the watch and its engravings.

The first report found the engravings to “predate the vast majority of superficial surface scratches,” while the second report revealed nothing to contradict the previous conclusion.

A recreation of Jack the Ripper in a London street(Image: Liverpool Echo)

A recreation of Jack the Ripper in a London street(Image: Liverpool Echo)

The third report added: “From the limited amount of evidence that has been acquired it would appear that the engraving on the back of the watch has not been done recently and is at least several tens of years old but it is not possible to be more accurate without considerably more work.”

These investigations left open the possibility of a forgery, but with the stipulation that the forger would have needed “considerable skill, and scientific awareness.”

Further issues with the diary’s content brought Maybrick’s alleged guilt into serious question. The diary bizarrely ends with an expression of regret and renewed commitment to his wife and children, which is without precedent in all other known serial murder cases.

The author writes: “Remind all, whoever you may be, that I was once a gentle man. May the good lord have mercy on my soul, and forgive me for all I have done.

“I give my name that all know of me, so history do tell, what love can do to a gentle man born. Yours truly, Jack the Ripper.”

Undated poster for the capture of Jack The Ripper. PRESS ASSOCIATION photo. Photo credit: PA….A…General News(Image: PA)

Undated poster for the capture of Jack The Ripper. PRESS ASSOCIATION photo. Photo credit: PA….A…General News(Image: PA)

In 1995, suspicions of forgery appeared to be proven correct. On Jan 5 of that year, Michael Barrett quoted that final sentence in a sworn affidavit confessing his forgery of the diary. In the confession, Barrett claimed he and his wife had conspired to frame Maybrick as his personal history fitted conveniently with the Ripper murders.

Barrett claimed he had decided by late 1993 to distance himself from the diary after the publisher, Robert Smith, and the author of the book in which the diary was published, Shirley Harrison, had excluded him from royalties.

He further claimed his wife, from whom he was later divorced, had worked with a documentary team working on a film about the diary to threaten him if he went public with his confession.

Anne Barrett (later Anne Graham) did indeed continue to make money off the diary. She published her own book six years later exploring Florence Maybrick’s life, in which she claimed to be related to her.

She also claimed, contrary to the original story, that the diary had been in her family’s possession since WWII, and that she had given the diary to Devereux to give to her husband as she didn’t want him asking questions of her estranged father.

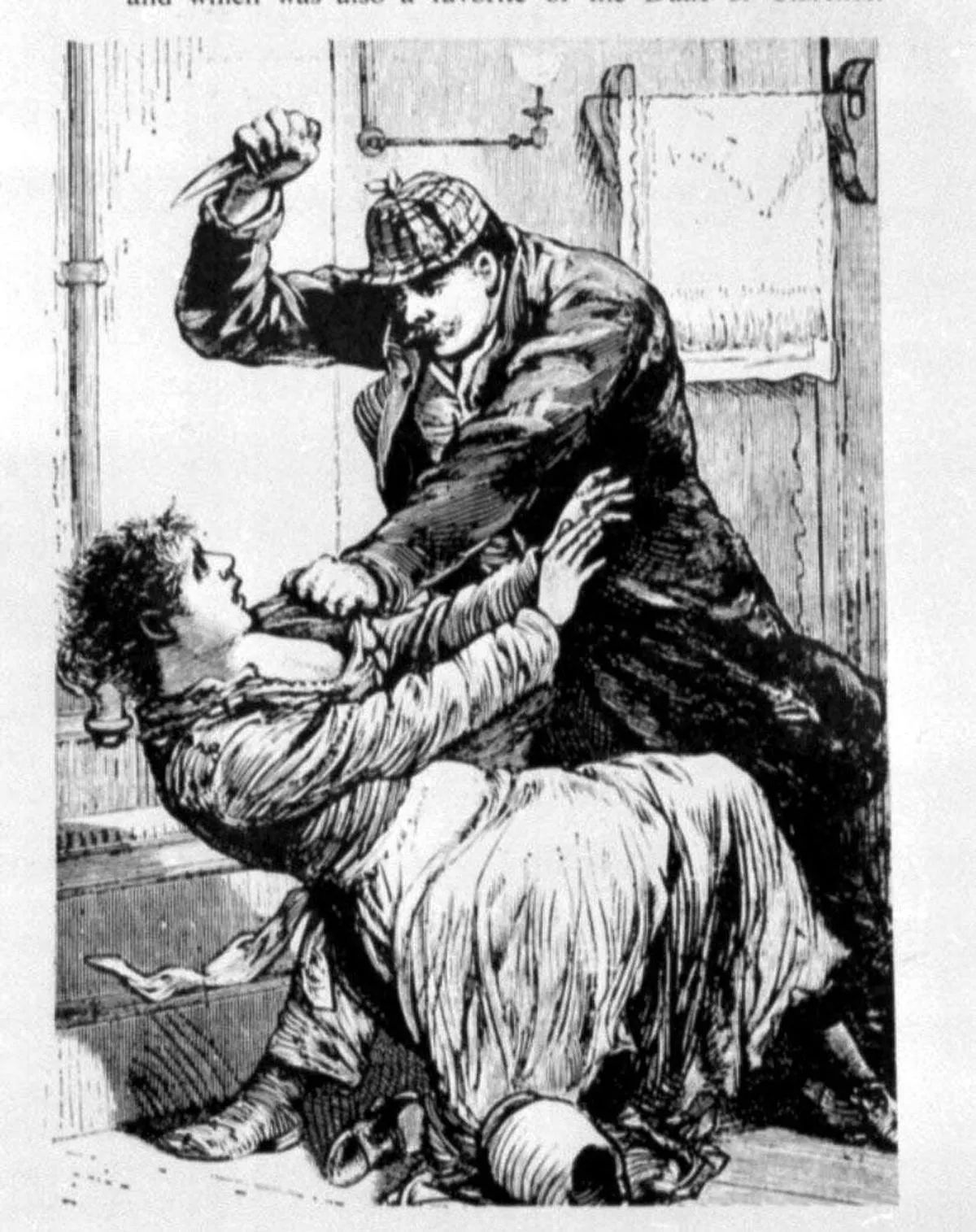

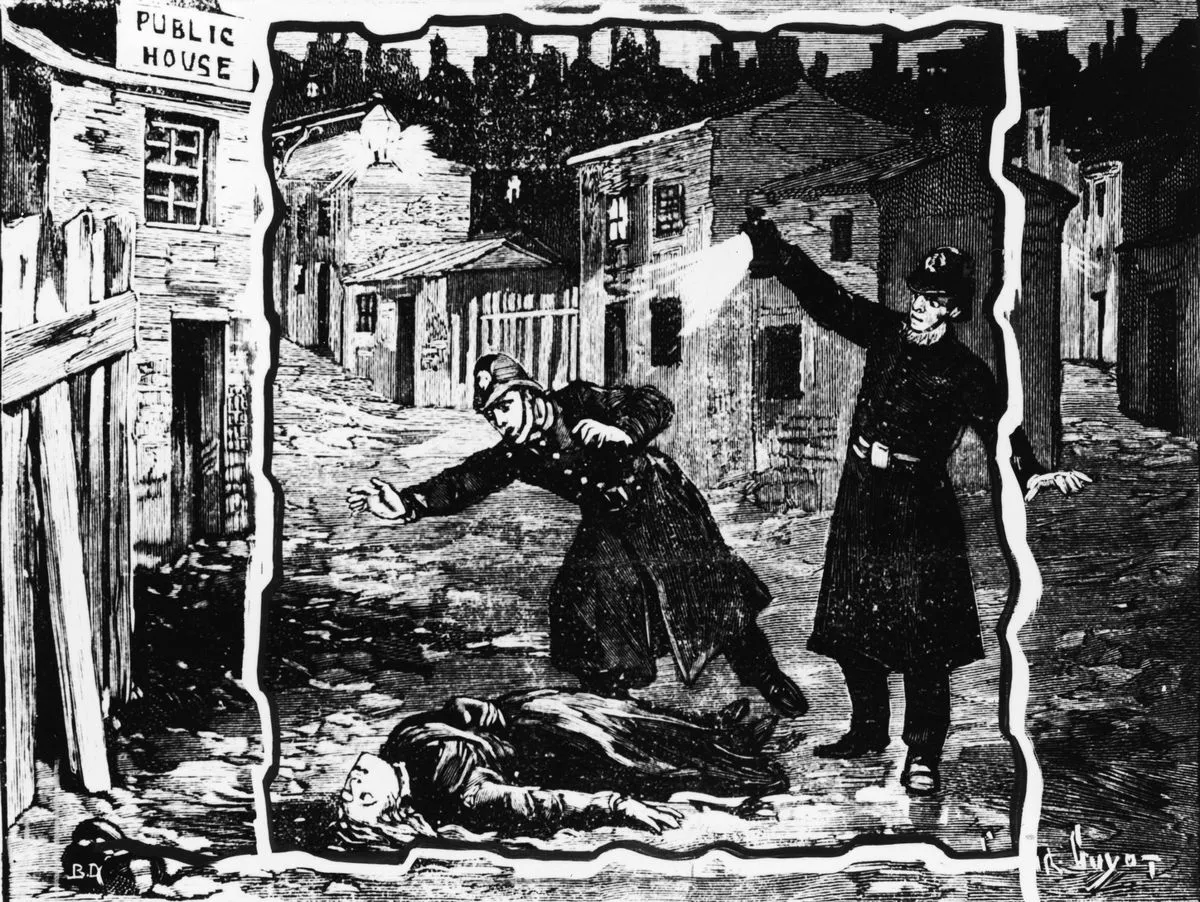

Illustration shows the police discovering the body of one of Jack the Ripper’s victims, probably Catherine Eddowes, London, England, late September 1888. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)(Image: Getty Images)

Illustration shows the police discovering the body of one of Jack the Ripper’s victims, probably Catherine Eddowes, London, England, late September 1888. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)(Image: Getty Images)

The furore around the diary ultimately discredited its authenticity, and most experts now agree that James Maybrick was not Jack the Ripper. Diaries alleged to belong to Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler that captivated the media were famously proved to be forgeries, and if anything only tell us that nothing gets in the way of a good story.

Even if it was – as seems likely – a forgery, Maybrick as the Ripper is close to a perfect fit. His motivation to kill sex workers coming from a deep resentment of his wife, Florence, matches a crime scene photo from the murder of Mary Jane Kelly: the Ripper’s final victim. The photo appears to show the initials “FM” written in blood on the wall behind the victim’s body.

While it’s plausible Barrett could have been motivated to make a false confession out of spite, with his wife and publisher making money at his expense, this seems like a stretch.

Michael Barrett said: “My wife was clearly under the influence of this man [Paul] Feldman (of MIA Productions Limited, the team working on the Maybrick diary documentary), who I understand had just become separated from his own wife.

“It seemed very odd to me that my wife who had been hidden in London for long enough by Feldman should suddenly reappear and work on me for Mr Feldman.”

circa 1889: Florence Maybrick, the wife of James Maybrick, a wealthy Liverpool cotton merchant thought to have been Jack the Ripper. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)(Image: Getty Images)

circa 1889: Florence Maybrick, the wife of James Maybrick, a wealthy Liverpool cotton merchant thought to have been Jack the Ripper. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)(Image: Getty Images)

The irony of his own wife seemingly leaving him for a rival in his field – in London, of all places – probably wasn’t lost on Barrett. In 1998, he was cleared of sending a death threat to Anne following her assertion she was related to Florence Maybrick, which would’ve meant the pair’s own daughter was a descendent of the man they’d claimed was Jack the Ripper.

Barrett admitted to sending the note, which the court heard read: “So help me God, push this one step further and I will kill you. I want you to know you can never walk the streets in safety.” He was cleared after successfully arguing it was not written with intent.

Is this a case of life imitating art? Maybe not. Barrett was never able to provide proof that he forged the diary, and spite towards Anne offers a compelling motive for a potential false confession. But his own downfall perhaps offers a hint as to how he was able to create the character of the Ripper so convincingly.

In 2016, a user on Ripperologist blog site Jack the Ripper Forums reported Barrett had died in January of that year. Anne’s whereabouts are unknown but a user in the same forum claimed she has distanced herself from the diary and the Ripper case.

With the late Tony Devereux the only other person connected to what Barrett claimed was the initial forgery, it is unlikely any concrete answers about what happened in Liverpool in the early 1990s will ever emerge, unless Maybrick’s diary – or the curious case of the gold watch – is ever conclusively proven to be authentic.

The controversy around the Barretts solves nothing, and only preserves the dignity of the victims as an uncomfortable afterthought. Still, the story of James Maybrick – and whatever connection he may or may not have had to Jack the Ripper – remains a beguiling chapter in the tapestry of Liverpool’s history.