David Bowie casts a long shadow. Not just in the countless films, books and podcasts exploring every last aspect of his 69 years on Earth, but over the lives of the people who shared a stage or studio with him.

“Honestly, ever since he left the world, something’s happened,” says Gail Ann Dorsey, Bowie’s bassist from 1995 to 2013. “I know it sounds hippie dippie, but something shifted. I wish I could ask him, where are we going, David?”

Bowie’s death on January 10, 2016 may or may not have caused a cosmic imbalance the likes of which we are yet to recover from, but it unquestionably had a huge impact on the people he worked with. Speaking to the key alumni of his 50-year career, some still feeling the pain of being discarded, others feeling blessed to have come into his orbit at all, similar descriptions of the man crop up. David Bowie was funny, personable, spontaneous, very good at bringing out the best in people — and totally unsentimental about ditching everyone and moving on.

On stage with bassist Gail Ann Dorsey in 2002

BERTRAND GUAY/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

“Nobody got fired, they just didn’t get called again,” says Carlos Alomar, who came in to play guitar for Young Americans in 1975 and stayed until Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) in 1980, before returning intermittently until Reality in 2003.

As Mike Garson, who provided the unforgettable avant-garde piano solo on Aladdin Sane in 1973, puts it: “Nobody doesn’t want to get the call from Bowie. Everyone feels dissed. But he was honouring his truth.”

• David Bowie remembered by Kate Moss — the friend he called ‘Smasher’

Nobody felt the sting of truth being honoured more than Woody Woodmansey. The last surviving member of the Spiders from Mars, with whom Bowie transformed from an Anthony Newley copyist to a glam rock alien, Woodmansey was drumming for rock bands in his native Yorkshire when he got the call from Bowie to move into Haddon Hall, his house in Beckenham, Kent, alongside Woodmansey’s guitarist friend Mick Ronson.

“All I knew about David Bowie was the curly haired guy from Space Oddity,” Woodmansey remembers. “This man in red corduroy trousers, blue shoes and a silver belt answered the door and said, ‘Hello, Woody.’ I was all in denim, so that was our first culture clash.

Mick Ronson, Trevor Bolder, David Bowie and Woody Woodmansey of Spiders From Mars in 1972

MICHAEL OCHS ARCHIVES/GETTY IMAGES

“He played me his old records and I thought he was trying to sound like other people. Then he performed Wild-Eyed Boy from Freecloud on an acoustic guitar, sitting a few feet from me, and I thought, he’s got something.”

Woodmansey says he could see the talent, but not much direction. “He could sing, he could write, he looked like a star. But nothing was in place and he worried about being a one-hit wonder. Then he went on a promo trip to America where he met Lou Reed and Iggy Pop, people who were completely themselves, and he came back saying, ‘I know what I need: more Bowie.’

“Next thing I know I’m in the kitchen, buttering toast, when he says he finished a new song while I was up in town. He plays Life on Mars and I’m thinking, ‘Holy shit. That’s incredible.’”

There were wild times at Haddon Hall. Woodmansey woke up one day to find the house filled with naked women, to be told by Bowie’s wife Angie that they were all lesbians. There was an attempt at a normal Sunday lunch with Bowie’s mother and his schizophrenic half-brother, Terry, where, after being asked what he had been doing, Terry replied: “Masturbating, mainly.”

• Revealed: David Bowie’s secret list of his favourite songs

But there was dedication to the job at hand, alongside a lack of preciousness that is cited time and again. Woodmansey says that for the 1972 album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, Bowie showed the band a song, got them to run through it once — and put the run-through on the record.

“That’s what he wanted, something edgy. And it was all about work. When we were making albums there was nothing stronger than coffee.”

By the time of Aladdin Sane, written on the road during an exhausting US tour and released in April 1973, Bowie was a star. On July 3 that year he announced the Spiders from Mars’ retirement from the stage of Hammersmith Odeon, which was the first they had heard of it. Then he sacked Woodmansey on his wedding day.

Woodmansey married June Harrison and was sacked from Spiders from Mars the same day

DAVID THORPE/GETTY IMAGES

“That was an effective way to piss me off,” Woodmansey says. “We had an argument with [Bowie’s manager] Tony Defries, when he said, ‘Bowie could have made it with anyone.’ But he didn’t, did he? Suddenly David was staying in different hotels, wouldn’t hang out after concerts. It’s only looking back now that I realise how much pressure he was under.”

“He fires the entire band on stage and I was the only one who knew,” remembers Garson, a garrulous, 80-year-old former habitué of the New York jazz scene. “I loved those guys, I was also the band leader, and here’s the thing. David was charming, charismatic, the friendliest guy I ever knew, and absolutely ruthless.

“From 1972 to 1974 he fired five bands. He let go of five musicians on the (1997) Earthling tour alone. But it was never for financial or careerist reasons. It’s because he was the Miles Davis of rock, always willing to change.”

And willing to learn from others. “He knew he couldn’t do it alone,” Garson says. “Why did I play so free on those records? Because all David did was give me a shape and allow me to do what I did. He didn’t micromanage.”

The pianist Mike Garson performed at Celebrating David Bowie in 2018

CHRIS MCKAY/GETTY IMAGES

Garson discovered his own services were not needed after Young Americans, but he was summoned back for the Black Tie White Noise album in 1993 and stayed until Bowie had a heart attack during a concert in Germany in 2004, effectively ending his live career. How did the two periods compare?

“During Aladdin Sane he was coked out of his mind. In the Nineties he’s getting married, he’s clean, he’s reading three books over three days on the tour bus. But the creativity was the same. It shows you don’t need drugs.”

The guitarist Earl Slick witnessed Bowie’s druggiest years in the mid-1970s, when he was making Station to Station, dabbling in fascism and the occult, and living on a diet of milk and cocaine. “Mick Ronson quit, he needed a guitar player, and I joined on the [1974] Diamond Dogs tour,” says Slick, a fast-talking New Yorker who learnt his chops from classic rock’n’roll. “The first thing I thought was, this guy’s looks don’t match his personality. He looked kinda weird but actually he was very down to earth.”

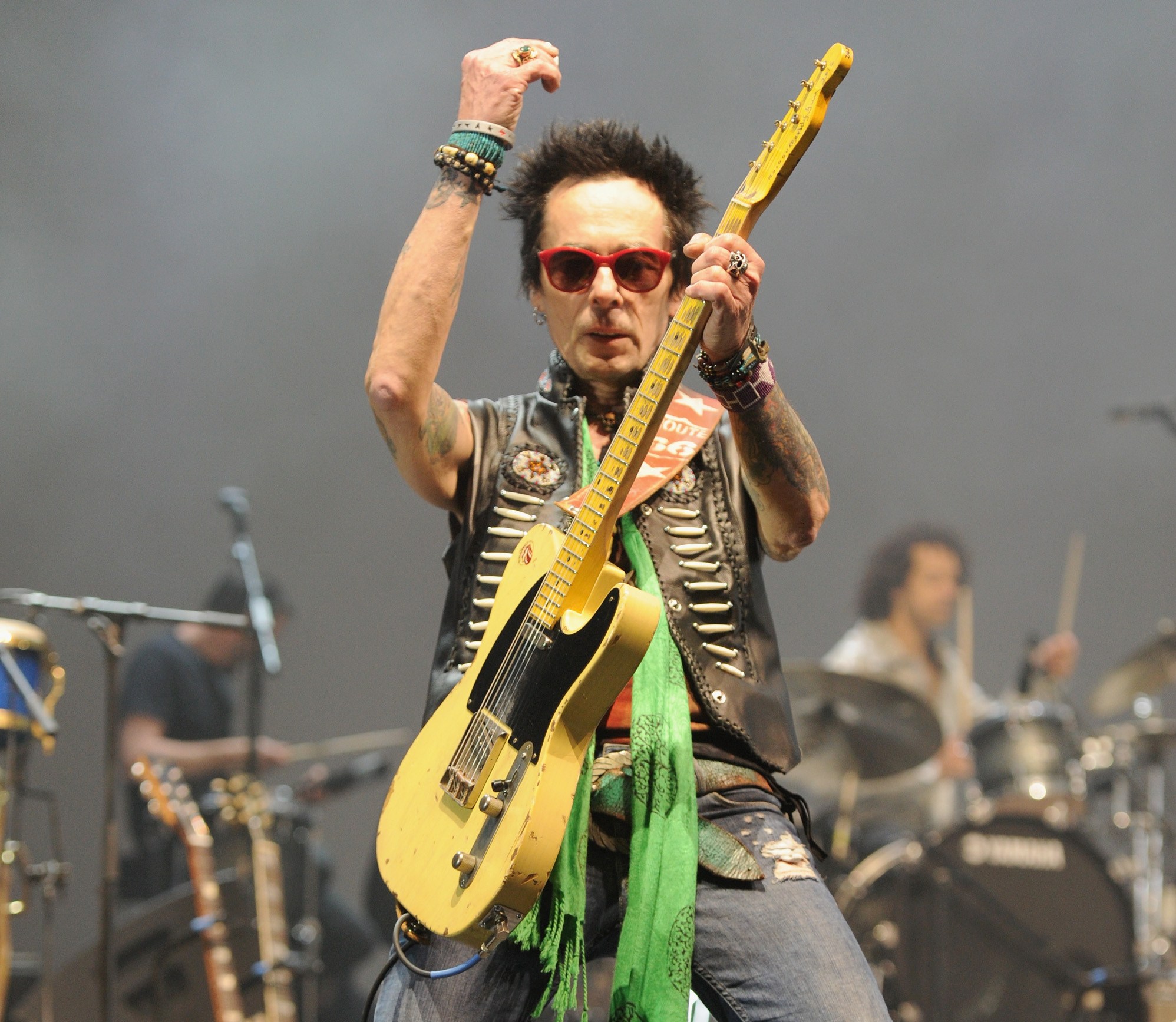

The guitarist Earl Slick on stage at Celebrating David Bowie with Gary Oldman & Friends in London, 2017

BRIAN RASIC/WIREIMAGE/GETTY IMAGES

At least he was at first. “Station to Station was a strange experience,” Slick says of an album that features ten minutes of funk-tinged paranoia on the title track but also the pop charm of Golden Years and a haunting take on the Nina Simone ballad Wild Is the Wind.

“David was definitely on another planet. But whatever condition he was in, he was still incredibly focused. I swear to God, there were times when I went into the studio Tuesday afternoon and came out Thursday. Then I show up the next day, the band shows up … no David. I guess he was sleeping it off. Hey, this was Los Angeles in 1975. We didn’t think anything of it.”

• David Bowie and Nazism — ‘I’d have been a bloody good Hitler’

Slick had no idea about Bowie’s lifestyle at the time, because outside the studio there was no communication whatsoever. “I only found out later he was closing the shades of his house, putting weird symbols on the door to ward off evil spirits, all that shit. When I came back [for Outside in 2002] he was a whole different person — joking, laughing, talking about the last trip he took. None of that happened in the Seventies.”

Alomar, who with the drummer Dennis Davis and the bassist George Murray made up Bowie’s funk-based backing band the DAM Trilogy, witnessed Bowie’s most dramatic changes through the Seventies: the “plastic soul” of Young Americans, the icy alienation of Station to Station, the experimentation of the ‘Berlin era’ albums Low, Heroes and Lodger, and the postpunk playfulness of Scary Monsters in 1980.

“This individual comes from overseas, doesn’t have anything, and he wants me to go on the road. But he can’t afford me,” says Alomar, already an in-demand guitarist for James Brown and Wilson Pickett when he got the call.

“He was a nice guy, wanted to know everything about the black experience, and I was attracted by his English accent, so when he tells me he wants to do this Philly soul sound I hook him up with my clique. And that kind of soulfulness, you have to study it, otherwise you’ll trample it. And as a white boy he really pulled it off.”

Respect duly earned, the guitarist stayed on Bowie’s ever-changing journey as, by Alomar’s description, “an actor who sings”. He also dismisses the cocaine engulfing the Station to Station sessions as a product of necessity. “You do a snort of coke and stay up all night so you can write two more songs. Will you be a wreck later on? Who cares?”

Moving to Berlin with Iggy Pop was a way of changing the lifestyle. The DAM trio played basic punk chords on Iggy’s 1977 album The Idiot before letting loose on Bowie’s Low.

• David Bowie’s secret final work: an 18th-century musical

“Was David testing us? Getting a juggernaut of a funk rhythm trio to do punk, the easiest music you can possibly play?” Alomar asks himself. “Who knows? But that’s when we worked in an intuitive way. On Low, [the producer] Tony Visconti would tell you the key, Brian Eno would set the tempo and you played something that fitted. Sometimes it might sound horrible but it was true experimentation.”

It was also a way of Bowie entering a new period of asceticism, away from the druggy excess of his LA years. “Berlin was dark and people didn’t want to live there,” Visconti says. “That’s why David was renting a three-bedroom apartment for next to nothing. If you travelled by car from East to West Germany you couldn’t stop for petrol. You had to make sure you had a full tank because if you stopped you would be shot.”

At least making Boys Keep Swinging in Switzerland in 1978 and 1979 was less dangerous. For this chaotic celebration of boyish freedom, Bowie had the idea of putting Alomar on drums, Davis on bass and Murray on piano, none of which they played. “He told us, ‘You sound too damn professional. You need to sound like a bunch of 14-year-old boys,” Alomar says. “Oh my God, it sucked! But it worked because, as David said, when you want to change the sound, change the band.”

Bowie was in London in 1988 when the Philadelphia-born Dorsey came on the television to promote her debut solo album. “He didn’t call me until 1995,” she says, giving insight into how his mind worked. “He said he now had a project that I was right for, which was the Outside tour. That’s when six weeks turned into 20 years.”

Dorsey puts Bowie’s constant reinvention down to a childlike spirit of adventure. “He was like a kid, excited about what he was doing next,” she says. “He didn’t second-guess himself and he was never precious, so there was an infectious work environment. He said to me once, ‘Putting together a band is like a director making a movie. A good director chooses the right actors, then sits back and lets them do their thing.’ He pulled things out of people before infusing himself into them — that’s Bowie.”

• The 26 David Bowie albums ranked — from worst to best

In 1999 Emm Gryner was 24, floating around New York after being dropped by her label, when she got the call to be Bowie’s backing singer and keyboard player. “I didn’t know much about him. I thought Rebel Rebel was by the Rolling Stones,” she confesses.

“I come from a traditional pop format, and the first thing I realised is that the keyboard lines in Bowie’s songs were never static like they are in pop. He let us just get on with it, which I thought was crazy, given the level he was at. One time I screwed up in a concert and didn’t even get the death stare.”

For Blackstar, that remarkable swan song of an album recorded in secret in early 2015 and released two days before his death, Bowie headed off in another direction. Having checked out Donny McLaslin’s experimental jazz quartet at the 55 Bar in New York, he hired the lot of them.

“I did my due diligence and went through his back catalogue,” McLaslin says. “But I learnt, very quickly, that he wasn’t interested in me replicating the sax part on Let’s Dance. He sent over rough home demos of Sue (Or in a Season of Crime), Lazarus and a few others, gave us the green light to do what we do, and it was wonderful.”

The saxophonist Donny McCaslin: “I learnt very quickly that he wasn’t interested in me replicating the sax part on Let’s Dance”

GARI GARAIALDE/REDFERNS/GETTY IMAGES

Of Bowie’s old gang only Visconti, who first worked with him in 1968 after arranging the flop single In the Heat of the Morning, made it through to Blackstar.

“Just before Christmas we talked about our families,” the producer remembers. “Then he said, ‘I’ve got new material, nothing special, but after New Year’s we’ll get together and I’ll show it to you.’ That’s the way David worked: he came up with a few chord changes, but never wrote a lyric or melody before stepping into the studio. I was excited.

• Read more music reviews, interviews and guides on what to listen to next

“Then he went silent. I got the devastating news in a hotel room in Toronto, which I didn’t see coming at all. He was always so optimistic about his health.”

Most of the Bowie alumni had no idea he was even ill. “He wouldn’t have liked us calling up and asking how he was,” Dorsey says, by way of explanation. “He wasn’t sentimental. Very British in that way.”

Since then they have all paid tribute to their old boss in one way or another. Visconti and Woodmansey have played his songs in the band Holy Holy, McCaslin put together a 65-piece orchestra for the Blackstar Symphony, and in 2025 Alomar got the old DAM trio back together for a European tour. Gryner, Dorsey, Slick and Garson have backed the British songwriter Rob Fleming for his Bowie-influenced band KillerStar while also staging their own Bowie concerts. Ten years after his death, Bowie’s ghost lingers.

“David’s genius was to be the ultimate collaborator,” Garson concludes. As his alumni keep the flame alive while countless new artists take inspiration from his endlessly various body of work, David Bowie is still collaborating. He’s just not here to do it in person.