Insider Brief

- A new theoretical study finds that quantum entanglement may remain distinguishable in principle even after one particle crosses a black hole’s event horizon, challenging the assumption that such correlations become completely inaccessible.

- The researchers show that fundamental limits on how precisely quantum states can be localized leave a small but nonzero statistical difference between entangled and non-entangled states measurable outside the horizon.

- The result does not enable information to escape a black hole or offer near-term experimental tests, but it reframes how physicists think about measurement, localization, and information loss in curved spacetime.

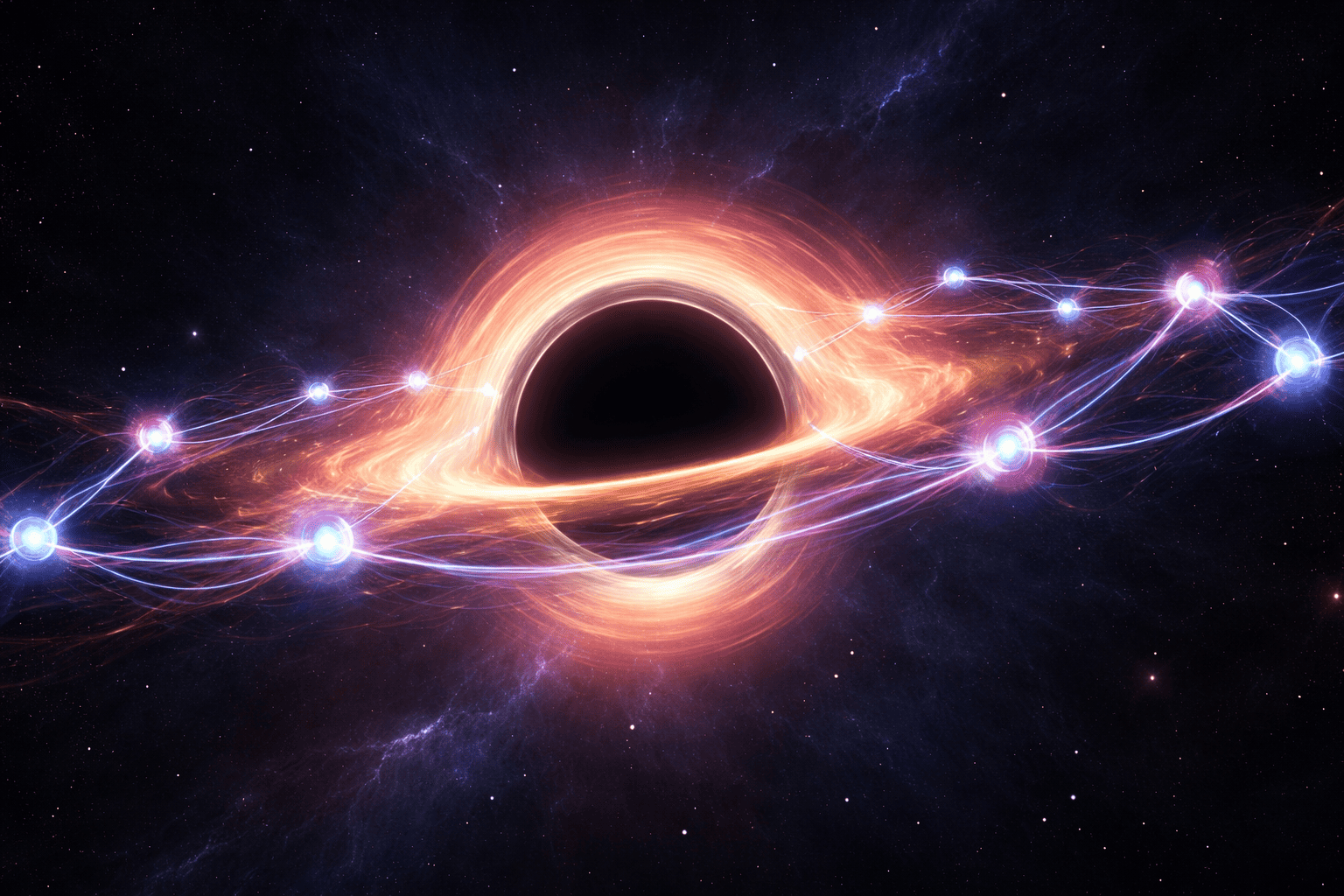

Quantum theory suggests entanglement may leave a detectable trace even when one particle vanishes behind a black hole’s event horizon, according to a new theoretical study that challenges long-standing assumptions about what information is truly lost to gravity.

In a paper posted to arXiv, physicists Patryk Michalski and Andrzej Dragan, both of the Institute of Theoretical Physics, University of Warsaw, report that two quantum particles can, in principle, remain distinguishably entangled even after one falls past a black hole’s point of no return. The result does not claim that information escapes a black hole, nor that signals can be sent from inside it. Instead, it suggests that subtle limits in how quantum states can be localized allow outside observers to tell whether entanglement existed in the first place.

The finding touches on how quantum mechanics, which treats information as fundamentally preserved, fits with black holes, which appear to erase it. It’s one of modern physics’ most stubborn questions. While the work is theoretical and far from experimental reach, it reframes a problem often treated as settled — that anything crossing the event horizon becomes forever inaccessible.

According to the researchers, the key lies not in exotic new physics but in the imperfect way quantum states occupy space.

Answering The Unanswerable?

The event horizon of a black hole marks the boundary beyond which nothing, not even light, can return. For decades, physicists have assumed that if one member of an entangled pair crosses that boundary, any measurement performed outside the black hole would look identical whether the pair was entangled or not.

Michalski and Dragan challenge that assumption by asking a more operational question: what can an observer actually measure, given the limits imposed by quantum theory itself?

The study considers two quantum wave packets — localized bundles of probability rather than point particles. One packet falls into a black hole, while the other remains accessible to an outside observer. The observer’s task is to determine whether the initial state of the two packets was entangled or separable, using only measurements that are physically allowed outside the horizon.

Conventional reasoning says this should be impossible. If one packet is hidden, all measurable information about correlations should vanish with it. The study points in another direction.

They show that because quantum states cannot be perfectly localized — a consequence of the uncertainty principle — some overlap between the accessible and inaccessible regions is unavoidable. That overlap, while extremely small, carries enough information to make the two scenarios distinguishable in principle.

The paper frames the problem using tools from quantum state discrimination, a branch of quantum information theory that studies how well different quantum states can be told apart when measurements are limited.

The conclusion is that under ideal conditions, and with optimal measurements, an observer outside the black hole could statistically distinguish an entangled state from a non-entangled one, even though one particle has crossed the event horizon.

Claim Limits

The researchers are careful to emphasize the limits of their claim. They do not propose a way to extract information from inside a black hole. Nor do they suggest that entanglement survives intact in any operational sense once a particle crosses the horizon.

Instead, the result rests on a subtle asymmetry that the particle inside the black hole is inaccessible, the particle outside is not perfectly isolated from it at the level of quantum fields.

In quantum mechanics, states are described by wave functions that spread out in space. No physical process allows a wave packet to be confined to an infinitely sharp boundary. That mathematical fact, the team suggests, undermines the assumption that the two scenarios — entangled versus separable — become operationally identical once one particle falls in.

The difference is extremely small with the probability of successfully distinguishing the two cases being low and depending on idealized measurements that are far beyond current technology. But the researchers stress that the distinction is not zero.

This paper is important because it challenges a scientific shortcut. Many arguments about black holes rely on treating “zero in practice” as “zero in principle.”

Black Hole Debate

The work enters a crowded and contentious field. Since Stephen Hawking’s discovery that black holes emit radiation, physicists have wrestled with whether information is destroyed, scrambled, or preserved in some hidden form.

Over the years, proposals ranging from holography to firewalls have tried to reconcile quantum theory with gravity. Most assume that the event horizon cleanly divides what can and cannot influence outside observers.

Michalski and Dragan’s result suggests that this division may not be as absolute as commonly assumed, at least when framed in operational terms.

The paper does not resolve the information paradox. But it weakens one of its simplifying assumptions: that entanglement across the horizon is completely invisible to the outside world.

By showing that distinguishability is, in principle, nonzero, the study reopens questions about how quantum correlations should be treated in curved spacetime.

The result also highlights the importance of measurement theory in gravitational contexts. Rather than asking what exists “behind” the horizon, the paper asks what can be inferred given the physical limits of measurement.

That shift mirrors a broader trend in quantum foundations, where questions of interpretation are increasingly framed in operational, testable terms.

The Researchers’ Analysis

The study models the two particles as quantum wave packets in a relativistic setting, with one packet crossing the event horizon of a black hole. The researchers then construct two possible initial states: one entangled, one separable.

They calculate how these states appear to an observer restricted to measurements outside the horizon. Crucially, they do not assume idealized point particles or perfectly sharp boundaries.

Using quantum state discrimination theory, they derive the maximum probability with which an observer could correctly identify which initial state was prepared.

The mathematics shows that this probability is greater than chance, meaning the states are distinguishable in principle.

The team also explores how the result depends on the shape of the wave packets and the observer’s measurement capabilities. In all physically reasonable cases, the distinction persists, though it may become exponentially small.

The paper emphasizes that the effect arises from fundamental properties of quantum fields, not from any speculative modification of gravity or quantum mechanics.

Limitations

Like all scientific endeavors the study has limitations and areas for future work.

The result applies to idealized scenarios with optimal measurements and perfect knowledge of the system. Real black holes, astrophysical noise, and practical detectors would overwhelm the tiny effects described.

The work also assumes a semiclassical treatment of gravity, where spacetime is fixed and quantum fields evolve on top of it. It does not incorporate a full theory of quantum gravity.

As a result, the conclusions should not be read as statements about what an actual observer could measure near a real black hole.

The study also does not address how entanglement evolves over long timescales or how it interacts with Hawking radiation. It isolates a specific question on whether two quantum states that differ only by entanglement become strictly indistinguishable once one particle crosses an event horizon. The researchers report the states would not be indistinguishable.

Future Work — And Where The Work Could Lead

While experimental tests are not on the horizon, the conceptual implications are likely to ripple through several areas of theoretical physics.

For researchers working on black hole information, the paper suggests that operational distinctions matter even when effects are tiny. Arguments that rely on perfect invisibility may need to be revisited.

For quantum information theorists, the work extends state discrimination techniques into curved spacetime, offering a framework for analyzing what information is accessible under extreme constraints.

More broadly, the study underscores a recurring lesson of quantum mechanics: boundaries that appear absolute in classical physics often become porous under closer scrutiny.

Future work could extend the analysis to different spacetime geometries, other types of quantum fields, or scenarios involving Hawking radiation. The team also points to the possibility of exploring related effects in analogue systems, such as laboratory setups that simulate horizons using condensed matter or optical platforms.

Those systems would not test black holes directly, but they could probe the same underlying principles about localization, measurement, and entanglement.

You may be asking — does this have any connection to quantum computing or quantum technology, in general, or does the writer just like to have his brains scrambled every once and a while. The answer: A little of the former, but a lot of the latter. The work has no immediate implications for quantum computing or communications, but it does draw on tools from quantum information theory that are also used to analyze the limits of measurement, error discrimination and entanglement in emerging quantum technologies. So, the connection is, like entanglement spread across the event horizon of a black hole, extremely small — but not zero.

It is an intensely technical paper. For a deeper, more technical dive into this study and the mathematics behind it, please review the paper on arXiv. It’s important to note that arXiv is a pre-print server, which allows researchers to receive quick feedback on their work. However, it is not — nor is this article, itself — official peer-review publications. Peer-review is an important step in the scientific process to verify results.