Scientists have documented the ginkgo-toothed beaked whale, a rarely seen deep-diving species, alive off the coast of Baja California, Mexico.

The animals surfaced during a survey that finally ended a five-year search for an unexplained underwater sound.

That sound, labeled BW43 – a shorthand code for one beaked whale’s call – had been turning up in underwater recorders without a face. Scientists were unsure which species produced it or where it originated.

Ginkgo-toothed beaked whale

The work was led by Dr. Elizabeth Henderson, a bioacoustic scientist in the U.S. Naval Information Warfare Center Pacific (NIWC Pacific).

Her research focuses on using long-term acoustic recordings to track whales, understand their behavior, and evaluate how Navy activities affect them.

A recent paper explains that before the survey, this whale was confirmed only from strandings and partial remains.

Beaked whales are widely regarded as among the largest animals on Earth that scientists still know very little about. Their deep-diving behavior and offshore habits keep them hidden from routine observation.

The new sighting finally connects those elusive animals to their ocean habitat and gives conservationists a clear starting point for protection.

Mysterious BW43 whale language

For a decade, hydrophones, sensitive microphones that record sound in the ocean, had been logging the BW43 signal across the North Pacific.

A study cataloged several unknown beaked whale signals, including BW43, and suggested that the call might come from Perrin’s beaked whale.

Researchers knew they needed to watch the whale produce BW43 so they could combine photos, genetic tests, and recordings in a single identification.

Starting in 2020, teams returned to Baja California each summer, towing listening arrays behind ships and scanning the water for animals.

The team sailed aboard a research vessel named Pacific Storm, using viewing platforms and towed listening arrays to pinpoint the whales.

During the expedition, they recorded 21 BW43 detection events and saw five groups of Mesoplodon beaked whales in the same area.

A juvenile male passed within 66 feet (20 meters), allowing a crossbow biopsy that removed a plug of skin for genetic tests, which later confirmed the species identity through DNA analysis.

Tusks used for fighting

Adult males grow two flat leaf-shaped teeth near the tip of the snout that form small tusks as they mature.

These tusks do not help with feeding, which relies on suction, but are used by males when they fight over access to females.

Photographs from the encounters show adult males covered with long white tooth rake marks, bruises, and healed cuts tracing a lifetime of conflicts.

Many animals also carry circular scars from cookie cutter sharks, small predators that gouge round chunks of flesh from larger animals during quick bites.

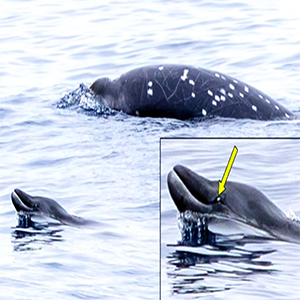

A juvenile/subadult ginkgo-toothed beaked whale, Mesoplodon ginkgodens, and the BW43 pulse (#2b, lower left) swims along with the same adult male (#2a, upper right) from Figures 3 and 4. The erupted tooth of the younger individual is just visible (arrow, inset), and it does not have white scar tissue around it or bruising, presumably because it has not been fighting with other males yet; the lips on the lower jaw are just starting to turn white. Credit: C. Hayslip. Click image to enlarge.Why sightings are so rare

A juvenile/subadult ginkgo-toothed beaked whale, Mesoplodon ginkgodens, and the BW43 pulse (#2b, lower left) swims along with the same adult male (#2a, upper right) from Figures 3 and 4. The erupted tooth of the younger individual is just visible (arrow, inset), and it does not have white scar tissue around it or bruising, presumably because it has not been fighting with other males yet; the lips on the lower jaw are just starting to turn white. Credit: C. Hayslip. Click image to enlarge.Why sightings are so rare

Beaked whales are among the deepest-diving mammals, making foraging dives that reach over 3,000 feet (914 meters) and last an hour.

The ginkgo-toothed species appears to follow that pattern, spending long stretches underwater hunting squid and fish before surfacing briefly to breathe.

When they finally surface, beaked whales usually spend just a few minutes at the top, far from shore, before descending again.

Their long dives and low surface time, together with boat avoidance, help explain why this species eluded surveys for decades.

Tracking with BW43

Because researchers have now tied BW43 to a known species, acoustic monitoring can reveal where ginkgo-toothed whales live without visual sightings.

Networks of seafloor recorders, ship-towed hydrophone lines, and drifting buoys can all pick up the distinctive click trains that make up BW43.

Besides the biopsy, the team also collected environmental DNA, genetic traces animals leave behind in seawater, which matched the whale species detected acoustically.

By combining acoustic detections, genetic matches, and photo identification of scars, researchers can estimate population size and seasonal movements.

A juvenile/subadult ginkgo-toothed beaked whale, Mesoplodon ginkgodens, and the BW43 pulse. It has a dark eye patch and a barely discernable dark eye band that travels up from the eye patch and over the back, behind the blowhole; it has a pale, anterior eye spot just in front of the dark eye patch. Credit: Pusser. Click image to enlarge.Beaked whales, noise, and BW43

A juvenile/subadult ginkgo-toothed beaked whale, Mesoplodon ginkgodens, and the BW43 pulse. It has a dark eye patch and a barely discernable dark eye band that travels up from the eye patch and over the back, behind the blowhole; it has a pale, anterior eye spot just in front of the dark eye patch. Credit: Pusser. Click image to enlarge.Beaked whales, noise, and BW43

Beaked whales have turned up in unusual mass strandings after naval sonar exercises, suggesting that powerful mid-frequency sound can disrupt their diving behavior.

Knowing where ginkgo-toothed whales occur allows navies and regulators to route sonar training or loud industrial work away from their core habitats.

The same listening networks can also reveal whether shipping lanes, seismic surveys, or fishing activity overlap with key foraging grounds for this species.

Early acoustic records indicate that ginkgo-toothed beaked whales may be resident off California and northern Baja rather than occasional vagrants.

The study is published in Marine Mammal Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–