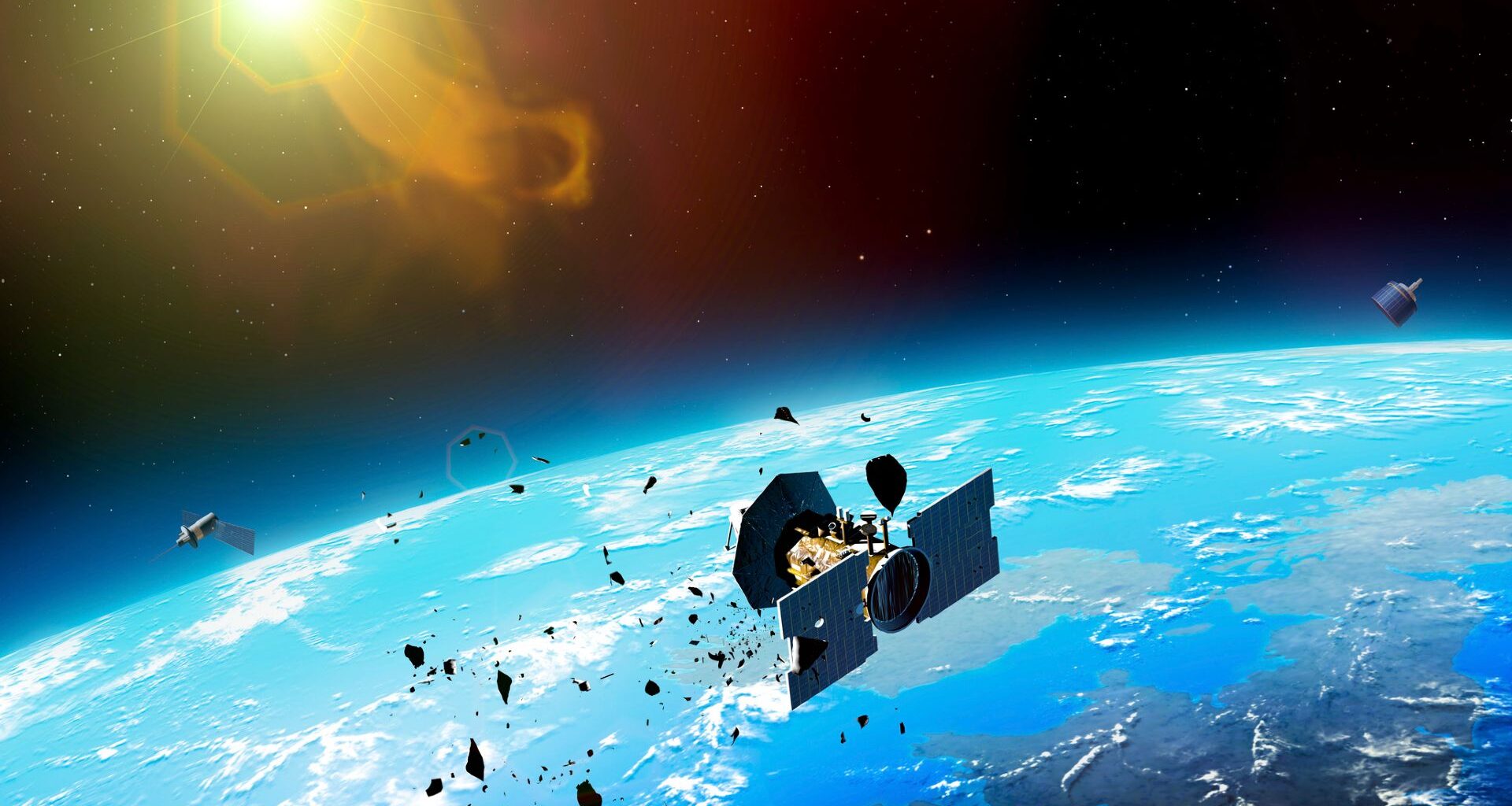

Space debris is a growing problem, and not just in Earth orbit.

Once a week, on average, a spacecraft (or part of one) falls back into Earth’s atmosphere; most of these objects are empty rocket stages, but some are dead satellites whose low orbits finally decayed enough for them to slip into the atmosphere. They’re basically like human-made meteors, but most of them don’t survive long. This is because of the heat and shredding force that come with high-speed collisions with the air. However, some bits of debris from the objects can exist long enough to plummet through the sky, ranging from dust-mote-sized particles to whole propellant tanks. And this can be a big problem.

There’s a risk one of those stray pieces can hit a passing aircraft — that risk is small, but it’s growing enough that experts are now trying to figure out how to reduce it.

You may like

We’ve been lucky so far

Even in space, what goes up sometimes comes back down: spent rocket stages, defunct satellites and other bits of space debris are falling back into Earth’s atmosphere with increasing regularity. And as satellite constellations and general spacecraft operations continue to become more common, the risk of deorbiting space debris will only go up.

There’s a 26% chance that sometime in the coming year, space debris will fall through some of the world’s busiest airspace during an uncontrolled re-entry, according to a paper published early in 2025 by researchers at the University of British Columbia. The odds of that debris actually striking an aircraft (or vice versa) are small but measurable: By 2030, the chances of any given commercial flight hitting a piece of falling space debris could be around 1 in 1,000, according to a 2020 study.

Those odds don’t sound terribly daunting if you’re the gambling type, but given the number of planes crisscrossing the friendly skies at any given moment, that’s a lot of rolls of the dice. And it’s a high-stakes gamble; risk includes not just the likelihood of an event, but the potential outcome (hundreds of people dead, in this case of that 2020 study). That’s partly because commercial aircraft carry so many passengers, but it’s also because it takes a much smaller bit of debris to cause a catastrophe in the air than on the ground, especially where jet engines are concerned.

“Aircraft can be affected by much smaller pieces of debris. For example, airplanes flying through the ash of a volcano is risky because of the small particles,” European Space Agency space debris system engineer Benjamin Virgili Bastida told Space.com. “Kind of a similar thing could happen with re-entering debris.” Virgili Bastida and his colleagues recently published a paper in the Journal of Space Safety Engineering outlining the challenges of deciding when and where to close airspace for falling space debris.

Lessons learned from Long March

One of the best known incidents of space debris affecting air traffic happened in November 2022, when the core stage of a Chinese Long March 5B rocket re-entered Earth’s atmosphere. It was the fourth time a Long March 5B had made an uncontrolled re-entry, and this time its ground track passed over Spain, prompting a flurry of airspace closures.

The Long March rocket was an unusual problem even by space debris standards; the roughly 20-ton core stage was much, much more massive than most spacecraft and rocket parts that drop back into the atmosphere (and China is no longer using that version of the rocket now that the final modules of its Tiangong space station are in orbit). China’s space agency also wasn’t very forthcoming about the rocket’s track or the fact that it was going to re-enter the atmosphere at all. But despite being an anomaly, the Long March incident is also a good illustration of both the potential danger and the need for more specific warnings, rather than broad ones.

Despite a few other close calls and airspace closures in recent years — like a SpaceX spacecraft that re-entered over European airspace in the summer of 2025, prompting airspace closures — we’ve been lucky so far. But maintaining that streak, without causing air-traffic gridlock by closing too much airspace for too little reason, is going to require a lot of work on multiple fronts.

You may like

“What we are trying to investigate in the studies we are running is to see what is really the threshold for risk for an aircraft,” said Virgili Bastida. “At what risk should we react?”

Other pieces of the puzzle include limiting the amount of debris that even makes it to the altitudes where most planes fly (around 30,000 to 40,000 feet or 9,144 to 12,192 meters), more accurately predicting where and when spacecraft will re-enter, and coordinating between space agencies and air traffic controllers to make the decision-making progress less clunky. And none of that is as easy as it sounds.

Really wide margins of error

It’s still surprisingly hard to predict exactly where and when an uncontrolled satellite is going to fall into the atmosphere. Even during a doomed spacecraft’s final orbit or two, the margin of error allows for several hours, which translates into thousands of miles of distance due to the speed most re-entering satellites move. The huge uncertainty presents air traffic controllers with a difficult choice: take no action and risk lives (even if the chances are small), or close a huge swath of airspace, which will inevitably cost millions of dollars and create air traffic delays that take hours to unsnarl.

For example, the 2022 Long March 5B airspace closure in Spain delayed, canceled, or rerouted more than 300 flights; Enaire (the Spanish equivalent of the FAA), shut down a strip of airspace about 62 miles (100 kilometers) on either side of the rocket stage’s path for about 40 minutes. But the debris only spent about five minutes of that time in the affected airspace, according to Virgili Bastida.

“There’s a desire to be more specific and make those windows and closures as narrow and constrained as safety allows,” space and aviation analyst Ian Christensen, senior director for private sector programs at the Secure World Foundation, told Space.com. Christensen added that both the FAA and the International Civil Aviation Organization are already working with the space launch industry — companies like SpaceX, ULA and Blue Origin, among others — to develop narrower, more specific airspace closures for rocket launches. Those efforts are likely to apply to dealing with the other end of spaceflight, returning debris, as well.

To get there, space agencies and air traffic controllers need two key types of information. First, when and where will the spacecraft hit the atmosphere? How much of it will survive intact down to 40,000 feet? Exactly what part of the sky will that debris be falling through (and when)?

Second, how big a threat is that debris to a passing aircraft? That answer depends on the size, speed and features of the aircraft, and researchers are in the process of working out models that can offer more specific answers. It will then be up to space agencies and air traffic controllers, working together, to decide when the risk is high enough to close a patch of sky — and for how long.

“If we react at every risk, half of the world will be impacted every now and then, so it’s not feasible,” said Virgili Bastida. “Do we react for everything which has a chance to reach the ground? Or do we react only for the very large objects, as we did for the Long March?”

Agencies in charge of aviation and air traffic control in individual countries (like the FAA in the U.S. and the Civil Aviation Administration of China in China) will eventually have to define how much risk requires them to close airspace for falling space debris. That could include factors like the likely size of the pieces and the chances of an impact, so a standard might look something like, “If there’s a 1 in 3,720 chance of particulate matter getting sucked into a jet engine, we should close the airspace.” (Those numbers are just for illustration.)

Better predictions need more data

The margin of error is so large, in part, because we don’t really know much about the detailed physics of the upper edge of the atmosphere, between 62 and 124 miles (100 and 200 kilometers) up. The term “upper edge” is misleading, in fact, because the transition from vacuum to air is more gradual, and the altitude where it happens depends on temperature and other factors — including how active the sun is at that moment. All of those factors affect how quickly the atmosphere’s drag can slow down a spacecraft and pull it in.

Satellites don’t spend much time passing through this rarefied region, and most of them are already dead and in the process of being disintegrated by the friction of the thin air against their hulls.

“There is very little information on this region of the atmosphere, so the models are just kind of extrapolated down or up,” said Virgili Bastida.

Building better models requires more data, and one way of getting that data is ESA’s upcoming DRACO (Destructive Re-entry Assessment Container Objective) mission. When it launches in late 2027, DRACO will measure — in 200 sensors’ worth of detail — exactly how a small satellite disintegrates during its plunge into Earth’s upper atmosphere. Its goal is to measure not just the spacecraft’s trajectory on the way down, but exactly when different components burn or break apart.

To do that, DRACO’s lead system engineer Alex Rosenbaum and his team are fitting the DRACO capsule with components in a range of different materials, each outfitted with sensors to measure its temperature and the time and altitude of its fiery demise. There will even be a mock-up of a propulsion bay and a composite fuel tank, even though DRACO won’t actually have working propulsion. The capsule itself won’t survive, which is the point. A black box, similar to the flight data recorders used on commercial aircraft, will escape the high-altitude breakup via parachute.

“It is a very peculiar mission because it will be very short,” Rosenbaum told Space.com. “We are working for several years on a mission that will be operative for a couple of hours.”

Meanwhile, there’s the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee — a group of 13 space agencies whose members include JAXA, ESA, Roscosmos, CNSA and ISRO. IADC runs an annual exercise called a Re-Entry Campaign, in which members choose “an interesting test case” from among the defunct satellites due to drop back into Earth’s atmosphere in the coming months. Member agencies pool their information on the object and their predictions about the time and path of its re-entry. Afterward, they compare what actually happened to their predictions in order to help test and refine those models. It’s steady work with cumulative results — not too dramatic but very important.

The Re-Entry Campaigns and DRACO will help improve predictions and shed light on how to reduce the amount of space debris by designing satellites and rocket stages that disintegrate as completely as possible at high altitudes. But once space agencies and air traffic controllers have that data, someone is going to have to decide what to do with it.

What exactly does that look like?

Agencies have to talk to each other

First, air traffic controllers and national aviation authorities will need good information from, and regular communication with, the agencies that monitor space traffic and space junk. In the U.S., the FAA and the Department of Transportation, both of which regulate space launches as well as aviation. And at the United Nations, the U.N. Office for Outer Space Affairs is working with the Secretariat of the Civil Aviation Authority to build the kinds of connections that help experts exchange data and work together on studies.

And second, since the paths of re-entering spacecraft often cross national borders, aviation agencies and air traffic controllers in multiple countries will need to be able to communicate and plan. The Long March 5B incident in 2022 demonstrated what happens without that coordination: the Spanish airspace closures “concentrated and forced aircraft into other areas, which were still, anyway, under the remaining track,” according to Virgili Bastida and his colleagues in their paper.

Building the kind of coordination that could make the next incident go more smoothly is crucial — and it needs to happen before the next incident, according to Virgili Bastida and his colleagues. That coordination is likely to take the form of standards: criteria and guidelines that define what’s appropriate to do in a particular situation. In aviation, standards come from national agencies like the FAA and the European Union Safety Agency, or from international organizations like the International Civil Aviation Organization (a U.N. agency).

“The aviation world is very driven by standards, and we’re seeing a lot of activity in the space world around standards as well,” said Christensen. “Those give us ways to develop technical mitigation approaches, technical solutions, and then implement them at the national level with some coordination internationally.

“The sky is not going to fall on your head”

We may be approaching a future where closures or delays for re-entering space debris are as common as weather-related delays now. But if Virgili Bastida gets the world he’s hoping for, that future is one in which we won’t even notice, because re-entries will be predicted in advance and flight plans can just route around the affected areas.

“I’m optimistic that at the technical level and at the operational level, we’ll be able to work on this issue and make significant success,” said Christensen.

In the meantime, Virgili Bastida suggests that while policymakers and engineers need to be thinking about space debris and air traffic, the average traveler shouldn’t lose sleep over the risks.

“The probability of being hit by space debris is very low, much lower than any other risk that we have in normal life. So even if there are many re-entries and it’s kind of worrisome, it should not be your main worry,” said Virgili Bastida. “The sky is not going to fall on your head. But we are working on ways to do it even better.”